In the previous two articles, I discussed the background required for starting pranayama, and then outlined a practice of postures which can be used as a preparation of the mind and the body for pranayama. This final article will have a look at how to go about setting up for a basic pranayama session.

Before coming to pranayama itself, For more extensive guidelines and suggestions please refer to Light On Pranayama by BKS Iyengar and Yoga a Gem for Women by Geeta S Iyengar.

Time of day to practice

When to practice is a question which is often asked. Traditionally pranayama is done early in the morning, before other activities. Classically, just before sunrise. Early, even if not precisely at dawn, is ideal for many as it is a time we can organise without the interruptions of work and family. It is also when we have a mind that is less cluttered with the events and preoccupations of the day. Our body may be a little stiff, but potentially neutral. Pranayama at this time offers a clear start to the day, a moment to be self-reflective, and to set up good patterns of breath and mindfulness for the next 24 hours. It gives us an idea of how we actually are, as it helps us become aware of the effects of our activities the day before and to undo any remaining imbalances. During a session of pranayama, we may notice, for example, that we feel a bit jangled from too much coffee the previous day, are heavy in the body from slow digestion or are full of leftover thoughts that are still worrying us. Taking 15 or 20 minutes for pranayama can help us regain equilibrium. It also enables the body to function more efficiently on an organic level by opening the chest and lungs, stimulating the diaphragm, and facilitating digestion and elimination.

The end of the day is another possibility, and for some is more feasible. There may be a degree of end of work lethargy or tiredness but some people clearly function better at this point of the day. After a quiet evening practice of a sequence of restorative postures as indicated in the previous article, the breath is quite tangible. If we are able to bring the mind to quietness and receptiveness, the body is often looser by the afternoon and the ribs and chest are more pliable. Pranayama at this time of day can be soothing and refreshing.

On a practical level, first thing in the morning has the advantage that we have not yet eaten. As it is essential to practise on an empty stomach and at least half an hour to an hour away from asana practice a session later in the day can take a bit more planning. However 15 minutes or so of quietening ourselves through supported poses and savasana at the end of posture work is often enough to prepare for pranayama, and for some practitioners, this is when they are at their most receptive mentally.

Given the possibility, a “perfect” yoga day would involve: early morning pranayama followed by a break of half an hour or so, an active asana session, and then a practice of inverted postures and perhaps a few forward bends or restorative poses at the end of the day before dinner. If we can manage this it interesting to see what it is like to spend a day or even two or three centred around yoga. It gives us a reference point, an opportunity to see what practice is like without first needing to undo the rest of our day. Practice for the sake of practice. On a day to day basis though, given the demands most of us have, it is best to find what will actually work for us and do that. Consistency of practice, letting it become a part of our life is better than a burst of yoga here and there.

Location

A clean and quiet place where we can remain undisturbed for the duration of the session is best. It takes a little time to settle into the neutrality and stillness required for clear breath observation. It is difficult to break off and then try to come back to where we were or need to be. Plan a shorter session if necessary but endeavour to keep the time free of distractions.

“Hints and cautions”

This is a phrase used by Mr. Iyengar in Light on Yoga and Light on Pranayama to describe some important points to consider when establishing a pranayama practice. These sections from the above-mentioned books contain more specific suggestions about how to practise. I refer you to those texts for more in-depth study.

For the purposes of this article, I will select just a few guidelines to follow when practising on your own. These are things that apply to any sort of yoga breathing you do. They have been useful for me to refer to when practising on my own, and much of it comes from the guidance I have received from the Iyengars during the past 25 or so years of attending classes and intensives with them.

- To be considered pranayama, the breath needs to be even, channelled and conscious. Breathing should never be done with effort and hardness. Mr. Iyengar has often said that pranayama will never come with force or hardness. We must learn to guide the breath, channel it with compassion, not with aggression.

- If the breath becomes short and jagged, rough, or uneven, it is time to do a few cycles of normal breathing or to stop for the day. Pranayama must have an even, smooth and harmonious sound and quality. If that smooth flow is lost, do not go on deepening the breath. When playing an instrument like the clarinet or recorder, the musician aims at producing a sound which is even and melodic rather than sharp and squeaky. The tone of your breath will tell you if you are doing it correctly. As with all things, it takes time to recognise the correct “note” for the breath, but we need to know that we are looking for it at least. If the sound of the breath is harsh, “squeaky” or jerky you may be forcing or going beyond your capacity.

- Ideally, each breath will follow on from the previous one with the same quality and sound, not each breath different from the last. A certain rhythm needs to be established. If the sound changes, if the rhythm is disturbed, try a few cycles of normal breathing before you again deepen the breath.

Tension in the face (eyes, ears, temples, throat, tongue)

The head and face are to remain passive and uninvolved with the breath. The chest alone is intended to be opened and illuminated with the breath, thrown into daylight; the limbs and face are to remain quiet and inert, dark, and cool as night.

The tendency instead is for the head to lift and strain during puraka, inhalation, and tension can then be felt in the eyes and temples and the ears may become hot and “ full”. This is to be avoided during pranayama and will immediately tell us that we have gone beyond our capacity. Go back to normal breathing and reset yourself to neutrality before you deepen the breath again.

During rechaka, exhalation, the chest often sags and the ribs drop down towards the diaphragm. This restricts the breath in exhalation and tends to make us strain or push the final part of the outgoing breath. If this occurs pressure will again be felt, a sense that there is still breath in the lungs but it has nowhere to go. Keep the chest well lifted with supports as required (refer to later text) so that the chest remains open during exhalation as well as inhalation.

The eyes, ears, throat, and tongue need to be quiet and soft throughout pranayama. The head remains as a distant, dispassionate observer, watching the breath but unaffected by it. If heaviness, fullness, or pressure is felt here during pranayama, go back to normal savasana breathing. Never continue with hardness or pressure in the organs of perception.

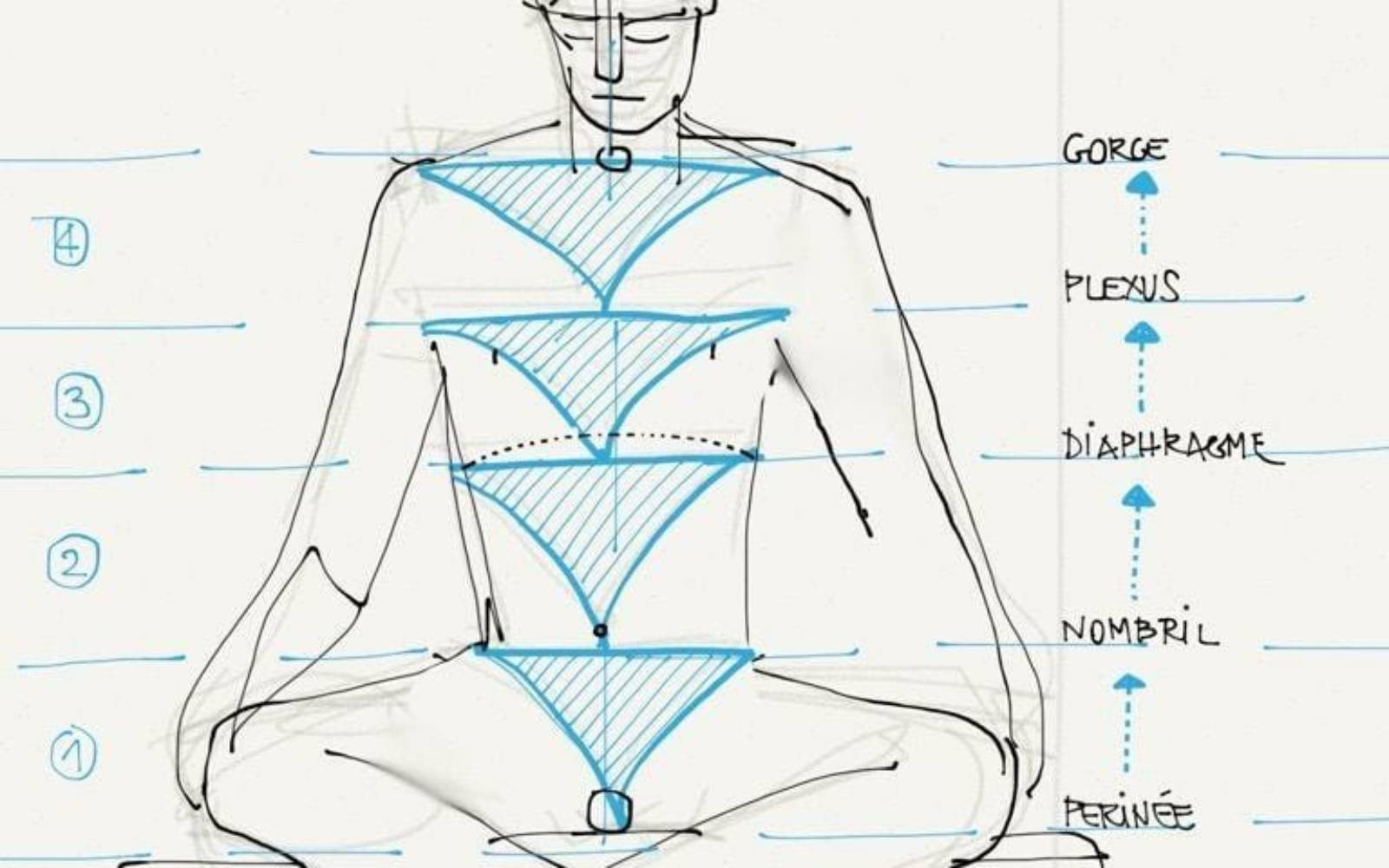

The synchronisation of the breath

- Synchronise the movement of the chest with the movement of the breath. The breath is the initiator and needs to give the opening and the direction for the chest to follow. Just as a ship moves through the water with the bow parting the sea as it makes its way forward, so too the breath creates the path for the body to respond. The chest opens systematically to receive the breath. We tend to lift the upper chest when the breath is still at the first “rung” of the lower ribs rather than let the breath climb up and the chest respond to its arrival. Let the breath open the chest from bottom to top on the inhalation. On the exhalation, the chest gradually releases as the breath moves out. The fullness of the chest recedes; don’t let it drop suddenly as the breath is exhaled.

- Never push the breath to the extent that the next part of the cycle is rushed or urgent. Anticipate the moment you need to inhale and exhale. Don’t try to extend the breath to the point where you have to grab for the next one.

- Become familiar with your normal rhythm of the breath. Mr. Iyengar often points out that unless we know our normal breath, pranayama will never be known.

Practice

For this article, I am going to assume you will be doing pranayama in the morning. If you are setting yourself up for a later practice, make sure that you have not eaten for the last two to three hours, that you have taken time to do a few restorative supported postures as previously described.

It may also be best to read the article first, set up your blankets, and then reread the relevant section just before practising. The guidance of a teacher in a class setting is ideal as they can pace the instructions and remind you of the important points as you go through the session. Here you will need to rely on your memory and perhaps reread the instructions a few times.

For early morning pranayama, prepare yourself by washing your face, cleaning your teeth, and organising a place to practise that is quiet and clean. Fresh air is important, so it is best to have warm clothing and a blanket to cover yourself with rather than having closed windows and an overheated environment.

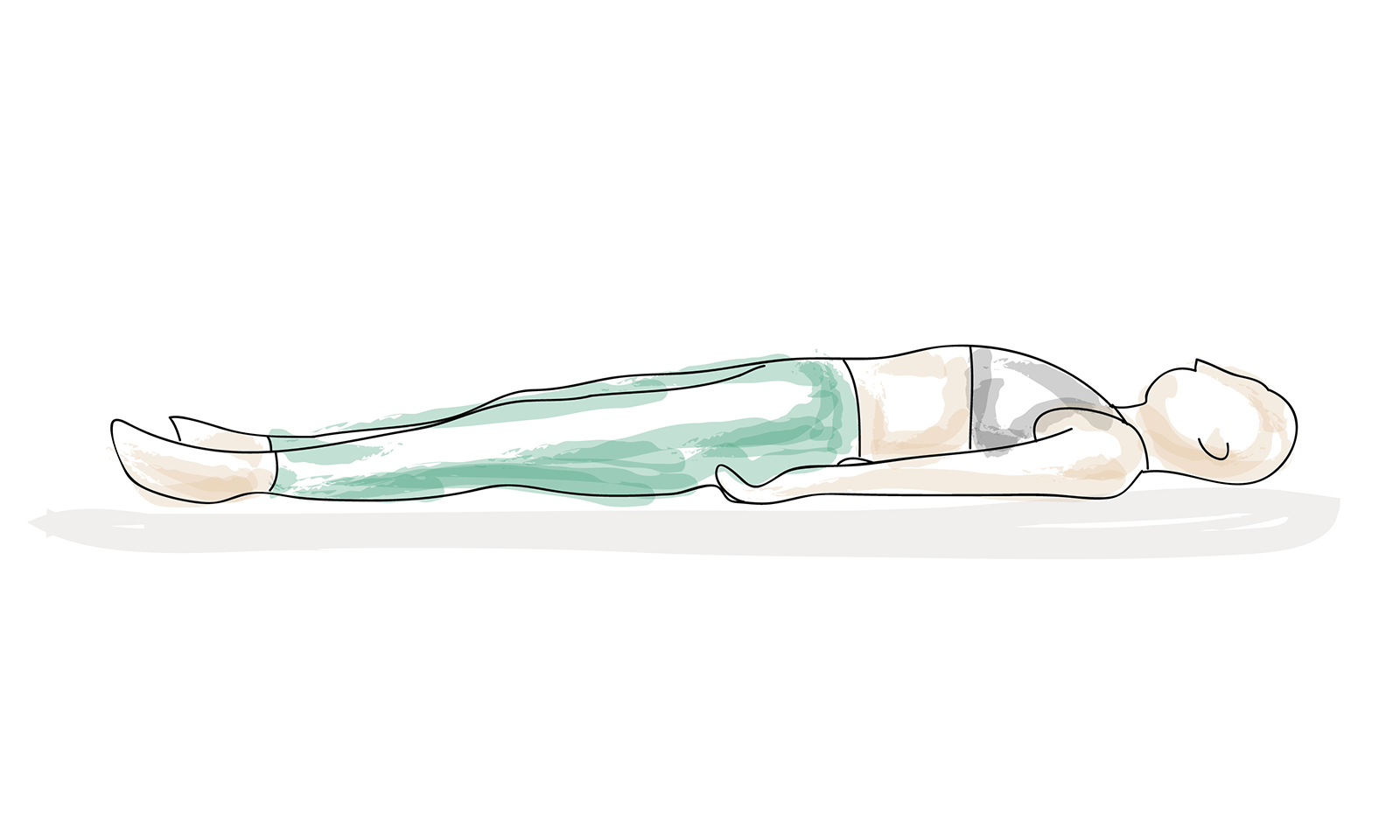

Set up two blankets each folded in half and placed along your mat as shown. Prepare a folded blanket for your head which is high enough to support your neck and skull so that it doesn’t tilt backwards. The height will depend on your body and your own requirements.

Lie back over the blanket as though going to savasana. Place yourself so that the lower blanket comes to the small of the back just above the top of the pelvis. The second blanket should start at the lower back ribs. The two blankets will be staggered a little so that there is a small space between the first and the second.

Lie back evenly over the blankets so that the spine is straight and the hips and shoulders are in line with each other. Adjust your head blanket so that it supports the whole back of your neck and head, starting at the base of the neck just above the shoulders. Check that the head is not tilting backwards and that the skin of the face is moving down towards the chin and throat.

Extend the legs out straight and then release them to the sides so that the outer ankles, knees, and thighs are rolling out and down towards the floor. Release the legs right from the top of the thigh rotating them from inside out.

Keep your spine long and in the centre of the blankets so that you feel evenness on either side of the spine with the blanket exactly in the middle of the back.

Rotate the shoulders down towards the floor, collarbones broad and the shoulder tips rolling down towards the floor. Allow the arms to turn from inside out right from the top of the arm near the shoulder to allow the outer elbows and wrists to turn down to the floor as much as the inner elbows and wrists.

Do not create hardness. Set your body in position mindfully and methodically but without forcing.

The aim here is to have the body at ease and yet maintain a certain alertness. The chest is supported to allow the back ribs and shoulder blades to slightly move up towards the front body. We need what Mr. Iyengar terms an “inner lift”, one which comes without muscular effort.

Relax your feet, your toes, your legs to the floor. Let go of the skin of the palms, the fingers; no tension anywhere.

Release all the muscles of the face, the throat, the tongue. Let the cheekbones soften and spread in the face. Let the space between the eyes grow a little wider to the sides.

Allow the eyeballs to sink down to the back of the eye sockets, away from the eyelids.

Let the eardrums move in towards each other deep inside the cavity of the skull. Quieten the face and keep the ears passive throughout pranayama. If any tension or hardness appears, go back to normal breathing and release the tightness.

In pranayama, the head remains passive and neutral as though watching objectively from a distance. The minute the brain becomes active, consciously quieten the organs of perception again.

It is not easy to remain neutral, “innocent” and open to the breath. It takes consistent practice. Learn to be aware when you have become disturbed in your eyes, ears, throat, or tongue. To “listen” to the breath that inner silence is necessary. It may take all your attention some days to quieten your mind during pranayama, but like a parent with a small child who is constantly running off you just need to keep bringing your mind back to the body, back to the breath. It is useful not to allow frustration to take over. Just one even steady breath with complete mindfulness is something to be satisfied with. This is an ongoing practice and in the end, is neither good nor bad but just is whatever comes on that day.

The mind is mostly elusive and difficult to control and it is, therefore, helpful to approach the mind through the physical body. If we can keep the eyes still and quiet, the brain also becomes more still. We cannot order the mind to be passive or make the breath smooth. We can though set ourselves up to enable these things to occur. It is more about undoing at first, clearing the decks in order to make space for the breath.

Ujjayi pranayama

First, allow the body to settle physically into the pose. Then consciously begin to observe your normal breath. Watch how the breath moves, in normal breathing, from different points in the chest.

Bring evenness between the inhalation and the exhalation. Which one is longer, which one is shorter. Lengthen the shorter one and diminish the duration of the longer one so that there is a steady and even flow. Give and receive the breath in equal quantity.

Is the right lung more active than the left, or vice versa? Bring more alertness to the dull side so that both sides are evenly receiving and releasing the breath.

Begin to observe the movement of the breath at the level of the lower floating ribs. Watch how the ribs open on the inhalation, recede on the exhalation. This also helps to bring us more inside, less concerned with the outer world.

Feel as you breathe the space within the cavity of the chest. Experience the depth from the sternum to the back dorsal spine, the breadth from the centre out to the left and right.

Begin to deepen your exhalation, allowing the breath to move consciously, slowly, and smoothly out of the lungs, from top to middle to bottom lung. Release the breath evenly with a smooth steady flow, simultaneously from the left side and the right side of the lungs.

At the end of the exhalation, pause and release the lower abdomen towards the floor and then begin to consciously inhale, as though drawing the breath up from the pool of the abdomen. Let the bottom floating ribs spread to the sides, like callipers opening out at the beginning of the inhalation. Observe the movement of the breath as it spreads the lower ribs out and then moves up into the chest, like water filling a glass, expanding to the sides as it moves up towards the upper chest.

Allow the front ribs and sternum to be opened from behind by the movement of the incoming breath. Synchronise the movement of the breath with the opening of the chest.

Let your mind be with the breath, exactly in contact with each other. Where the breath is the mind needs also to be.

Let the lungs fill evenly and without force to the top of the lungs.

Do not take the breath up into the throat and head. Let the collar bones be like a lid for the breath, the gate where the breath stops. If you draw the breath up into the throat and face you may experience the fullness and pressure that was mentioned in the guidelines.

When the breath reaches that upper part of the lungs, just below the collarbones, pause, lift the chest again, and slowly, smoothly exhale, from the top of the lungs down through the middle chest to the bottom lungs. Let the chest slowly empty out. Like an air mattress gradually losing air, as the breath leaves the lungs the chest maintains its outer shape at first until more breath has been released. Then the outer form of the chest recedes. The diaphragm controls the exhalation, like a car in first gear slowly going down a hill. The control in the diaphragm is maintained until close to the end of exhalation. Then release it completely, soften the lower abdomen again, pause, and again start your next deep inhalation.

Continue in this way with one deep inhalation exhalation followed by a normal cycle of breath. If the steadiness and rhythm have been maintained, continue with two deep ujjayi breaths and then a normal cycle of breath.

Do not be ambitious in pranayama. Be mindful and conscious of when tension or shakiness has come in. At that point always return to normal breathing and release the tightness or hardness before you continue.

Practise in this way for 10 to 20 minutes or so, according to your capacity.

At the end of your session, finish with a deep inhalation and go back to normal breathing.

Observe if any tensions have crept into the eyes, the ears, the throat and release completely. Go back to complete neutrality, let go everywhere.

Remain for a few minutes in Savasana, with quiet, soft normal breathing. Let go of any hardness, let the breath become smooth and steady.

Observe the gentle touch of the breath in the nose as it moves in and out. Keep the inner membranes of the nose soft and feel where the breath touches on the inhalation and the exhalation. Don’t ‘do’ anything with the breath, just feel its quiet movement as it passes in and out. The body quiet

Without disturbing the stillness created, bend your knees and wait a moment there. Then slowly let your eyelids roll back keeping the gaze soft, as though the eyes were still sitting at the back of the eye sockets.

With an exhalation, roll to the right side and stay for a moment longer. As the thoughts begin to reappear it is time to get up. Finish the session with the mind still clear and quiet to retain the freshness of savasana.

Pranayama is daunting to some, others are eager to begin. For all of us it takes time to refine, a lifetime perhaps. But we can never learn if we don’t at some point start to practise. At first, it may be difficult to notice its more tangible effects. Continue to practise without an aim in mind, without looking for a particular outcome and you may find that it is capable of bringing about deep and quiet transformation.

The breath is subtle, yet powerful in its influence. It is a constant companion, intrinsic to our existence from birth till death, a vital force within.

It probably deserves our respect.