In his book The Tree of Yoga, BKS Iyengar makes the following statements:

“There are three transformations which take place in meditation. At the very beginning of his Yoga Sutras, Patanjali says that stillness of the mind is yoga. Later, he says that when a person is trying to still the mind, there is an opposition which occurs as new thoughts or new ideas arise in the mind. There is a tug-of-war between restraint and the rising thoughts as they come together. When there is restraint of thought, after a little while some new thoughts are born in the gap. How many of us have caught that gap between the restrained thought and the rising thought? The space between the restrained thought and the rising thought is a moment of passivity. In that moment there is a state of tranquillity, and a person who can increase that pause, that space between the restrained thought and the rising thought, is transformed towards the state of experience known as samadhi.”

We normally think of being calm as being in a state of tranquillity. This absence of tension is both attractive and a relief from the pressures of our daily existence. We desire this state and yet when we aim to rid ourselves of stress and the pressures that face us we fail to recognise that this state exists within us as much as it exists in the circumstances of our lives. We are inclined to focus on the external reasons for our stress and look to make changes in our routines and relationships in an attempt to lessen the stress and achieve some level of tranquillity.

When we practice Yoga we often experience calmness and tranquillity also and for many students, this is the aim of their practice and the sum of why they attend classes. Yoga however is concerned with a much deeper level of change. If the thoughts and moods that we experience in our lives are seen as the movements on the surface of the ocean of our consciousness, then what lies beneath this surface? Can we change in a more substantial way than merely changing the surface conditions? To do so we must examine the deeper levels of our consciousness. Embedded in Yoga is the principle of transformation. Is it possible that change is not merely an act of getting away from ourselves and our cares or changing our moods?

In the passage above, Iyengar signals that the gap between the thoughts is to be examined. We cannot merely act to hold the mind steady. A distinction is made also between restraining and rising thoughts; between concentration which limits the interruption from outside and the capacity to observe the source of thoughts. But what does it all mean?

Meditation

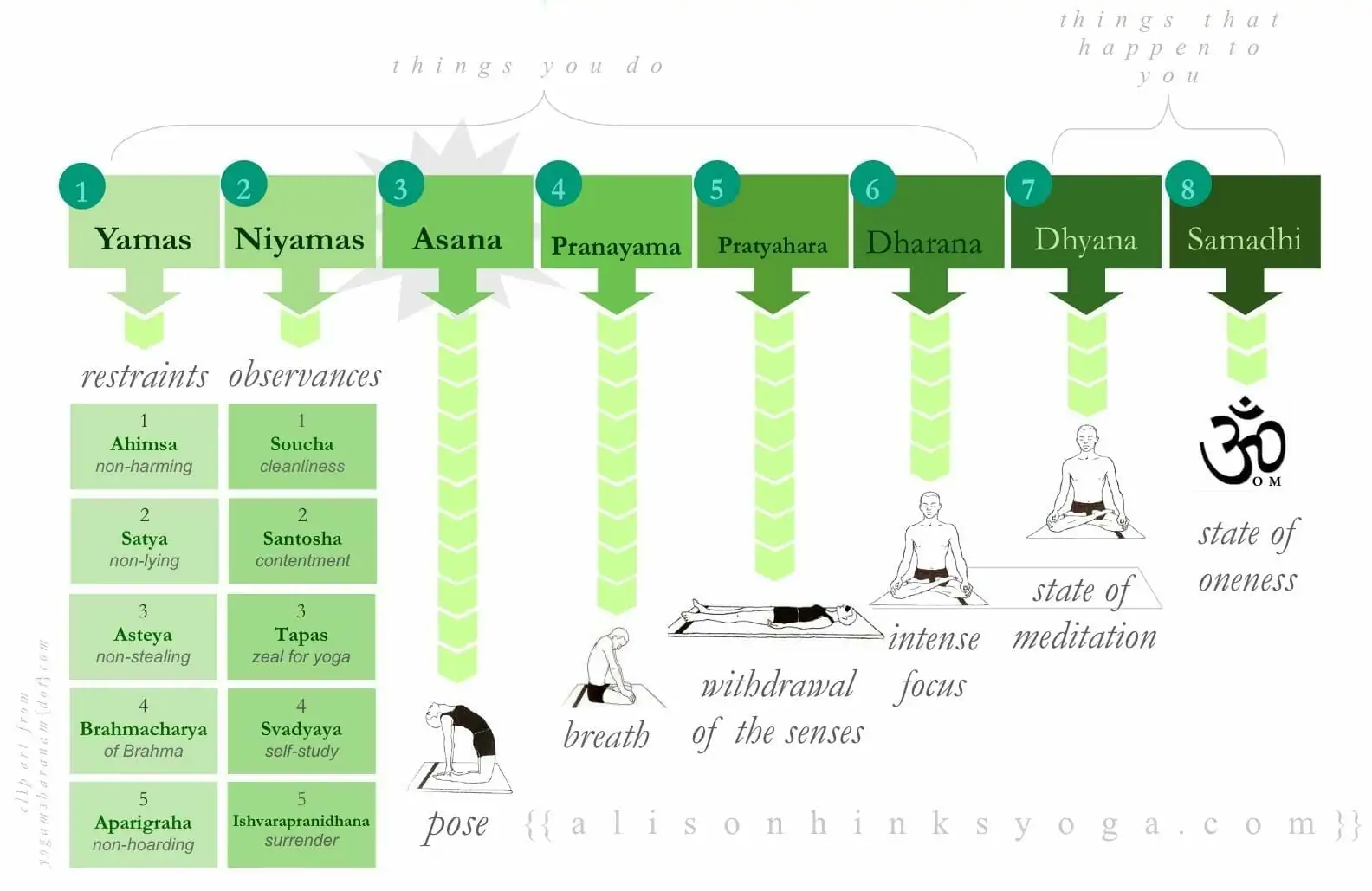

Before entering into a discussion on transformation we should first make a distinction in how Iyengar views meditation within his method of practice. Many of the so-called eastern disciplines consider meditation a practice; something to still the busyness of the mind. Through the practice of meditation techniques, we can cultivate a mind that does not wander. Iyengar however, makes a distinction. Within the eight limbs of Astanga Yoga enumerated by Patanjali Iyengar makes the following three groupings or classes. He groups the limbs into observances, practices, and outcomes in the following manner

“…. yoga is divided into three parts. Yama and niyama are one part. Asana, pranayama and pratyahara are the second part. Dharana, dhyana and samadhi are the third part. Yama and niyama are the discipline of the organs of action and the organs of perception. They are common to the whole world. They are not specifically Indian, nor are they connected to yoga alone. They are something basic which has to be maintained. In order to fly, a bird needs two wings. Similarly, to climb the ladder of spiritual wisdom, the ethical and mental disciplines are essential.”

Then, from that basic starting point, evolution has to take place. In order for the individual to evolve, the science of yoga provides the three methods of asana, pranayama, and pratyahara. These three methods are the second stage of yoga and involve effort.

The third stage comprises dharana, dhyana, and samadhi, which can be simply translated as concentration, meditation, and union with the Universal Self. These three are the effects of the practice of asana, prana, and pratyahara, but in themselves do not involve practice. Because there are tremendous variations in practice, there are going to be variations in the effect. If you work for two hours, you get only two hours’ salary. If you work for eight hours, you get eight hours’ salary. If you show initiative, you may get a rise in salary. That is how business works. Dharana, dhyana, and samadhi are like that also. If you work diligently on asana, pranayama, and pratyahara, you will receive your reward of dharana, dhyana, and samadhi, which are the effects of that practice. They cannot be practised directly. If we say that we are practising them, this means that we do not know the earlier aspects of yoga. It is only by practising the earlier aspects that we can hope to arrive at their effects’.

From these statements, we can comprehend Iyengar’s focus on the development of our practices (the second stage which he describes as involving effort). Through our practices, we can remove the obstacles, which hinder meditation. Our practices in effect create the conditions for the mind to become meditative. Therefore we do not practice meditation. In the same passage Iyengar goes further:

“Meditation is integration — to make the disintegrated parts of man become one again. When you say that your body is different from your mind, and your mind is different from your soul, that means you are disintegrating yourselves. How can meditation bring you back to integration if it is something which separates the body from the brain, the brain from the mind, or the mind from the soul?”

If closing the eyes and remaining silent is meditation, then all of us are meditating every day for eight or ten hours in our sleep. Why do we not call that meditation? It is silence, is it not? In sleep, the mind is stilled, yet we do not say that sleep is meditation. Do not be carried away – meditation is not so easy; it is like a university course. At the races, many horses run, but only one wins the cup. So also, we are all running in meditation but the winning post is far, far away from us because we have not conquered our senses, our mind, and our intelligence.

Transformations

In his celebrated yoga sutras, Patanjali names 3 transformations that take place in the mind in meditation. These are:

- nirodha parinama

- samadhi parinama

- ekagrata parinama.

What are they and what do they mean to the sadhaka (student)?

Nirodha parinama

Parimana means change and nirodaha is restraint. Iyengar describes it as:

‘…. the method used in meditation, when dharana loses its sharpness of attention on the object, and intelligence itself is brought into focus. In dharana and nirodha parinama, observation is a dynamic initiative.’

This first transformation indicates the change in the quality of concentration in our practice where the consciousness changes from a focus on the object to a focus on the mind. The mind becomes a watcher.

Samadhi parinama

Samadhi parinama indicates a state of tranquillity. Iyengar notes:

‘Through nirodha parinama, transformation by restraint or suppression, the consciousness learns to calm its own fluctuations and distractions, deliberate and non-deliberate. The method consists of noticing then seizing and finally enlarging those subliminal pauses of silence that occur between rising and restraining thoughts and vice versa.’

The pauses between breaths, which take place after inhalation and exhalation are akin to the intervals between each rising and restraining thought. The mutation of breath and mutation of consciousness are therefore identical, as both are silent periods for the physiological and intellectual body. They are moments of void in which a sense of emptiness is felt. We are advised by Patanjali to transform this sense of emptiness into a dynamic whole, as single-pointed attention to no-pointed attentiveness. This will become the second mode – samadhi parinama.

The second state is the pause or space created when a gap arises between the thoughts. Iyengar goes on to elaborate:

‘…Restraining the rising waves of consciousness and overcoming these impressions is nirodha citta or nirodha samskara. The precious psychological moments of intermission (nirodhaksana) where there is stillness and silence are to be prolonged into extra-chronological moments of consciousness, without beginning or end.’

Ekagrata parinama

A single uninterrupted point of awareness (Yoga Sutras, Ill, 9, ID, 11, and 12).

Ekagrata-parinama is the state where the mind, the body and the energy are completely focused towards the one base which is known as the core of the being.

The third transformation comes when we lose identity so there is no watcher; no identity from which we act. Iyengar clarifies this thread in the following statements:

‘……… the surface meaning of ekagrata does refer to one-pointed focusing on an object, but its deeper meaning is ‘one without a second’. There is the soul and nothing but the soul. When we recognize this profound meaning then the reason for Patanijali’s order is clear. Patanijali’s discussion of dharma, laksana and avasta parinama (III. 13) further clarifies this point.’

Consciousness has three dharmic characteristics; to wander, to be restrained, and to remain silent. The silent state must be transformed into a dynamic but single state of awareness. Patanjali warns that in restraint old impressions may re-emerge: the sadhaka must train to react instantly to such appearances and cut them off at their source. Each act of restraint re-establishes a state of restfulness. This is dharma parinama. When a serene flow of tranquillity is maintained without interruption then samadhi parinama and laksana parinama begin. During this phase the sadhaka may become trapped in a spiritual desert (see 1.18). At this point, he must persevere to reach oneness with the soul and abide in that state (avastha parinama) everlastingly. This final goal is reached through ekagrata parinama. (See 1.20.)’.

When we examine these statements of transformation a number of aspects are highlighted. These are changes in the consciousness. Changes in the way the mind is used and constitutes itself. The act of making the mind come to attention is an act of concentration but only a beginning; a precursor to a state of absorption. There is a role for concentration in our practice but there is an additional need for transformation from a purposeful state to a purposeless state.

When the mind is bought into concentration an act of will is applied as the mind is moved from its normal roaming state, oscillating from object to object, and achieves direction. This direction is turned towards a single object to the exclusion of other objects. However, a weakness remains as noted in the following passage:

‘As long as one impression is replaced by a counter-impression, consciousness rises up against it’.

As long as the force of exclusion is enacted to counter the oscillating mind the consciousness will inevitably rise. Like holding a ball under the surface of the water, it can only be held under as long as there is a force to do so. The rising force of the ball is not in the ball but in its relationship to the medium it finds itself within; the water. The ball will only stay under as long as I have the strength and desire to keep it there. The force used to direct the wandering mind becomes the rebound force that causes the mind to rise up.

Patanjali indicates that once concentration is established through volition, the nature of this concentration should be redirected towards the spaces between the thoughts. Our initial practice of directing the mind towards an object to achieve focus provides the means to observe the thoughts as they arise. This is not so much the content of the thinking but the rising nature of thought itself. Those thoughts just keep on coming…

By observing the gaps in the thinking process and moving into this space we collapse psychological time.

The precious psychological moments of intermission (nirodhaksana) where there is stillness and silence are to be prolonged into extra-chronological moments of consciousness, without beginning or end.

The importance of collapsing psychological time cannot be overemphasised. Any attempt to watch the thinking has the effect of prolonging time. We become aware of ourselves and so time appears to move more slowly than usual. Anyone who has sat quietly with a busy mind watching the passage of an hour will attest to the relentlessness of thought and the seeming expansion in the passage of time. But in this statement above Iyengar is noting the need to prolong ‘the precious psychological moments of intermission’ – to extend the gaps when time seems to pause; into ‘extra-chronological moments of consciousness, without beginning or end’ – so that the empty pauses can be extended in real-time. The effect is to achieve the third transformation where the sense of ‘I’ness dissolves. There exists an uninterrupted point of awareness where there appears to be no watcher (without identity).

A person who meditates is free from time. Probably many of you do not know what time is. We all know the word ‘moment’. The moment does not move. The moment is stable, but our mind does not see the moment – it only sees the movement created by the succession of moments. We see the succession of moments like the spokes of a wheel. The moment is the hub of the wheel and the movement of moments is the spokes. In meditation, the person who has mature intelligence lives in the moment and will not be caught in the movement of moments’.

When we exist in the sensations of our practice we exist from moment to moment. Sensations and breath do not exist in the past or future they exist only in the moment.

Theory and practice

Within the context of our practice developing a focus of mind is merely to bring the mind into concentration. By developing competence in the performance of asana and pranayama we achieve clarity in application. Having applied ourselves thus far is it possible to develop continuity in application so that an unbroken thread of awareness is developed. At this moment what is experienced is a sense of the loss of time.

This experience is not uncommon. Many students will have experienced where an hour may pass without awareness as they are absorbed in the practice. However, this is most often generated externally through the teacher’s actions of disciplining the student via their instruction. The question remains as to how the student will generate the same experience within themselves?

Initial efforts in asana and pranayama are haphazard and directed towards physical proficiency. As we progress and move from a learner towards studying our application of the asana we become aware of the fluctuating nature of our application. By working to develop continuity in application in our work it is possible to progress to a point of application where the mind adopts the same attribute of continuity. For this to happen a high level of familiarity and competence in physical practice is needed. By prolonging the continuity one is capable of dissolving the sense of time. We can exist in the act of asana. We can exist in the asana experience without experiencing time passing.

The attempt to dissolve psychological time therefore is an activity for a practitioner of yoga. Skilled in their practices and competent in asana. This attempt to create a pause in the passage of time is conscious and deliberate. The conscious pause could be summarised as a deliberate outcome of practice; a change in the consciousness. Thus the outcomes from our practices can be surmised as …. the transformation of the consciousness from purposeful (conditioned) state to a purposeless (attentive) state.