Yoga is described as a self study (svadhyaya) which ultimately means that we learn about ourselves through practice. Learning to practice is the aim of attending classes and this includes the routines and habits that support a practice. Yoga Mandir offers a range of learning pathways such as Yogasana courses, Led practices and material for home practice including sequences and study material.

Teachers communicate an experience of Yogasana based upon their own practice experience and through the practitioner program levels we offer courses rather than classes, endeavouring to be systematic in this communication. Teachers therefore seek to develop students as practitioners of yoga, rather than just encouraging attendance at classes. While it may appear that technical details of asana are a focus, over time the aim is for students to develop a capacity to focus on swadhyaya (self study). Swadhyaya is an aspect of Kriya yoga (tapas, swadhyaya and isvara pranidhana). Kriya yoga is one of Patanjali’s key approaches to the practice of yoga.

Yoga as Meditative practice

Yoga is classed as a meditative practice because it is concerned with the effects upon the mind. Whilst we work within a physical discipline both highly structured and refined ultimately the body is the vehicle to use the mind in a specific way. As we progress in our understanding of the techniques and in our application within the practice we develop concentration and we can begin to examine the behaviour of the mind. It is possible to think of our practice as directed towards performance outcomes in the body and therefore distinct from meditation but this misses its effects on the mind. In the practitioner program at Yoga Mandir we identify the practices (3 of the 8 disciplines of astanga Yoga) as being conducted to effect our inner state. Yoga is described as a culture of consciousness and the study of the mind.

Observances, practices and outcomes

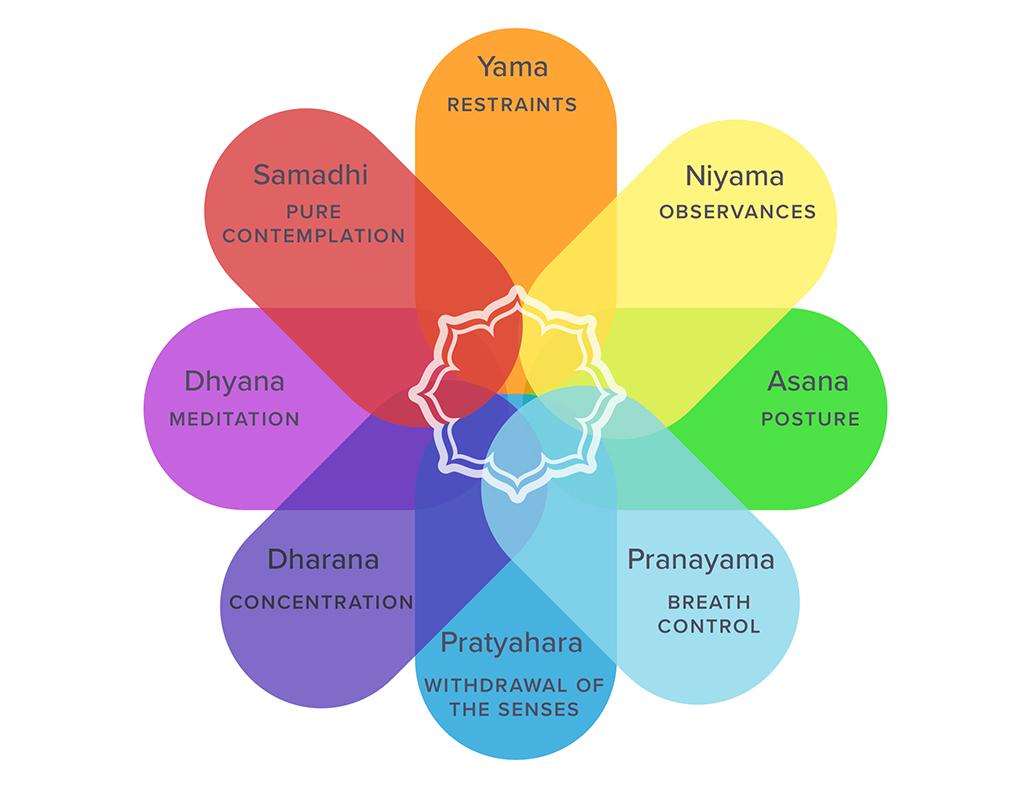

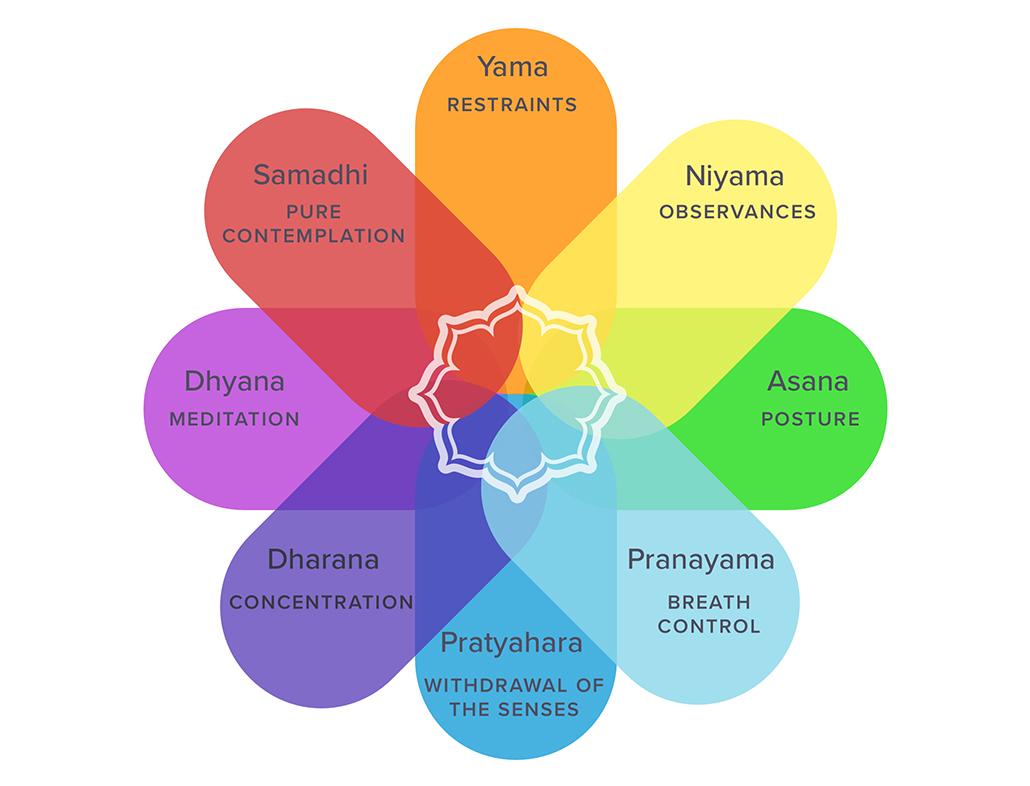

Iyengar divides the astanga (8 disciplines) of Patanjali into 3 groups below:

‘…yoga is divided into three parts. Yama and niyama are one part. Asana, pranayama and pratyahara are the second part. Dharana, dhyana and samadhi are the third part. Yama and niyama are the discipline of the organs of action and the organs of perception. They are common to the whole world. They are not specifically Indian, nor are they connected to yoga alone. They are something basic which has to be maintained. In order to fly, a bird needs two wings. Similarly, to climb the ladder of spiritual wisdom, the ethical and mental disciplines are essential.

Then, from that basic starting point, evolution has to take place. In order for the individual to evolve, the science of yoga provides the three methods of asana, pranayama and pratyahara. These three methods are the second stage of yoga, and involve effort.

The third stage comprises dharana, dhyana and samadhi, which can be simply translated as concentration, meditation and union with the Universal Self. These three are the effects of the practice of asana, prana and pratyahara, but in themselves do not involve practice.’

This third stage noted above is referred to as an outcome. When our practices (asana, pranayama & pratyahara) are conducted effectively they generate the outcomes of concentration (dharana), meditation (dhyana), and surrender (samadhi). In his book Tree of Yoga Iyengar uses the image of a tree to arrange the 8 limbs and uses the fruit to refer to the outcomes. Another term for the outcomes is samyama.

Samyama

The term Samyama is used to describe the last 3 aspects of the 8 limbed astanga system of Patanjali – dharana, dhyana, and samadhi.

Samyama is a technical word defining the integration of concentration (dharana), meditation (dhyana), and absorption (samadhi). In samyama, the three are a single thread, evolving from uninterrupted attention to samadhi.

Dharana is single-pointed attention. It modifies into dhyana by being sustained in time whilst dissolving its one-pointed character implicit in the word ‘concentration’. When it becomes all-pointed, which is also no-pointed (that is to say equally diffused, but with no drop in attentiveness) it leads to total absorption (samadhi). Continuous prolongation of these three subtle aspects of yoga thus forms a single unit, called samyama.

Samyama is a state of immobility, and a samyami is one who subdues his passions and remains motionless.

The following analogy shows the organic relationship between dharana, dhyana, and samadhi. When one contemplates a diamond, one at first sees with great clarity the gem itself. Gradually one becomes aware of the light glowing from its centre. As awareness of the light grows, awareness of the stone as an object diminishes. Then there is only brightness, no source, no object. When the light is everywhere that is samadhi.

As dharana is external to dhyana, dhyana to samadhi, samadhi to samyama, and samyama to nirbija samadhi, so the mind is external to intelligence, intelligence to consciousness, and consciousness to the seer. Dharana brings stability to the mind, dhyana develops maturity in intelligence and samadhi acts to diffuse the consciousness. Dharana, dhyana, and samadhi intermingle to become samyama, or integration.

Yoga Mandir recognises the significance of an intention to samyama through practice. To conduct samyama is to move away from knowing things about objects (for example the diamond mentioned in the quote above) and begin to look into the object. This is a very different use of the mind in which the mind seeks to achieve a meditative state. This is not a dullness of mind but could be described as a state of clarity beyond the habitual oscillations of mind which are so often clouded by the vrttis and klesas. We seek to move beyond thought and its limitations. Through a practice, we enter a state of stillness or contemplation.

Contemplative science

The term contemplative science may seem a contradiction. Science is generally thought of as being concerned with exactitude; with observable phenomena, with truth. It is applied to the world of quantifiable outcomes. Contemplation on the other hand is taken as subjective and therefore value-laden and thought of as being less objective and less reliable.

Science however increasingly accepts that the perception of the observer has a significant effect upon what is observed. The observer is rarely impartial and the expectation of an outcome will affect what is noticed and may overlook other aspects that appear irrelevant. A paper written in 1959 by Hemler and Rescher makes the case for the inexact sciences as being not less significant merely because they are unable to be verified independently. What stands at question is whether we can observe objectively and systematically. When we look into the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali we see a systematic articulation of the types of practice to be conducted, the states and modifications of the Citta (consciousness), along with the obstacles and afflictions the aspirant will encounter. Although difficult to verify independently there is a systematic engagement with the consciousness and its states.

In her book Yoga a Gem for Women Geeta Iyengar writes

Is Yoga a Science?

The science of Yoga consists of acquiring knowledge through observation and experiment. It is a science which deals with the body and the mind, whereby the rhythm of the mind is conquered by controlling the body. Through the practice of Yoga the health and strength of the body and the mind are acquired. Only when a state of equilibrium is reached between the body and the mind, does one become fit for Self-realisation. The science of Yoga teaches one to attain this harmony in a skilful and systematic way.

Contemplation is described as ‘The action of looking thoughtfully at something for a long time’: In this case, Yoga can be regarded as a contemplative practice as we return again and again to observe the behaviour and the movements and modifications in the consciousness. If we look thoughtfully at something for a long time we come to know it in a different way than if we look at it briefly or identify the object with a specific function. We recognise that the mind often delivers us to preconceived ideas and boundaries formed from past experiences. To contemplate something is to absorb its essence as Iyengar notes with the diamond. Just as we might contemplate an object we can contemplate the mind.

When we contemplate effectively within a practice we conduct a Samyama and for this reason, Yoga can be considered a contemplative science through practice. At Yoga Mandir, the practice is centred on 4 key methods to conduct a Samyama.

Methods: an application of principles

The term Iyengar Yoga was coined to describe the method of teaching Yoga developed by BKS Iyengar. Iyengar, however, states:

‘I have no right to brand my method of practice and teaching as “Iyengar Yoga”. It is my pupils that call it Iyengar Yoga to distinguish it from the teachings of others. Though I am rational, I am a man of sentiment and tradition bound. I trust the statements of others, follow their lines of explanation and experiment with them to gain experience. If my experience tallies with their expressions, I accept their statements. Otherwise I discard them, live by my own experiments and experiences, and make my pupils feel the same as I felt in my experiments. If many agree, then I take it as a proven fact and impart it to others …

… The only thing I am doing is to bring out the in-depth, hidden qualities of yoga to the awareness of you all. This has made you call my way of practice and teaching “Iyengar Yoga”. This label has caught on and become widely known, but what I do is nevertheless purely authentic traditional Yoga. It is wrong to differentiate traditional from Iyengar Yoga.’

Yoga is handed from teacher to student (guru to sisya) through practice. Each lineage develops specific practices and methods to achieve Yoga and examine the mind and consciousness. Methods are not merely applied to improve our asana presentation in the body, nor our flexibility alone. In a practice of Yoga we apply methods to overcome the afflictions and obstacles we encounter and engage in Svadhyaya (self-study). In the Yoga Sutras Patanjali directs us to apply Abhyasa/ Vairagya (action/dispassion), or Kriyayoga (tapas/self-study/surrender), in order to study the cause and effect of our actions. We shape our methods to undertake the 8 disciplines of astanga Yoga defined by Patanjali.

By applying specific methods we move our focus away from merely practicing positions of the body for flexibility, in order to develop knowledge from experience; to experience what Patanjali was communicating from his own practice experience.

In Yoga Mandir teachers apply four methods to the practice:

- Technique: comprises alignment, precision in performance, and use of props. The study of particulars in asana and pranayama is classified under technique and yet these form but one aspect of our overall practice.

- Timings: involves the use of holdings to develop sensitivity, to change one’s capacity, and to study oneself. The asanas should not be done for flexibility alone but as a refinement – yesterday’s poses with less effort smoother, lighter. By working with timings you develop the ability to let go in poses, to release tension in the pose. To stay you need to approach each pose from a different place, not merely from muscular strength but with increased intelligence.

- Sequence: the ordering of asanas in the practice to broaden the understanding and perception of an asana and of oneself.

- Repetition: applied when we return again and again over time to deepen our observation of the experience.

For example, the choice of a teacher to work ‘in sequence’ with the students holds a greater focus on sequence as a learning method. By participating in asanas being covered that day they leave the student to focus on their own experience of the practice. At another time a teacher may participate in a set of forward bends applying timings as a method. A student may discover something through the sequence or via the timings for example, when they are not distracted by the dialogue of techniques. This approach recognises that students learn in diverse ways and do not progress at the same rate nor will the same details seem significant at any point in time. Through the 4 key methods, students develop their experience and understanding of Yoga at their own pace.

There is a difference between Led practice and teaching a class in sequence. A teacher may choose to teach “in sequence” – calling the names of the asanas, demonstrating the asanas, and giving minimal verbal instruction. This shifts the students’ attention to observing the more subtle aspects of their own experience- for example, the citta and what rises within us. This approach is different from Led Practice. The intention to teach “in sequence” is different from the intention of a led practice.

The overarching premise and intention of Yoga Mandir is to develop practitioners of yoga. Using no words requires more of the student. To be worked by the teacher in a physically demanding way is relatively easy for a student. The student needs to generate less energy and self-motivation when the teacher drives the class.

Teaching Yogasana

The term Yogasana refers to the internal state contained within an Asana. In his book Alpha and Omega of Trikonasana Prashant, Iyengar states:

‘Once the body is positioned in the Asana… create a ‘condition’ in the embodiment which is the next step and the most vital, as it is in this internal conditioning which makes an asana a ‘Yogasana’.

Here the sadhaka learns to unite one part of the body with another part of the body, the body with the mind, the body with the breath and senses, also the breath with the mind and senses and this takes one into the inward journey which makes the practice of Yoga a Svadhyaya (self-study).

It is this unification which justifies the definition of the word Yog which means, ‘to unite’. Merely doing an asana by the body, through the body and for the body is not Yoga. Yogasanas are to be done by the body but for the mind, for the psyche, for the consciousness and for the culturing and refinement of a human being.’

The teaching of Yogasana strongly values the student experience of asana. We teach asana and pranayama along with the orientation of the indriyas (the senses) but we teach to the experiential moment. To do so is to acknowledge an experience of clarity and cohesion across all aspects of experience. What goes on in the body, the breath, the mind, and the consciousness is central to the teaching of Yogasana. Merely telling students how to do an asana is not teaching Yogasana.

As our understanding of Yoga is informed through the practices of Asana and Pranayama, it is essential to explore the use of Guruji’s method as a vehicle to clarify experience. Practice must become known and methodical in order to move into the subject. 2 quotes from Tree of Yoga helps place Guruji’s emphasis on practice:

Mahatma Gandhi did not practise all the aspects of Yoga. He only followed two of its principles — non-violence and truth, yet through these two aspects of Yoga, he mastered his own nature and gained independence for India. If a part of Yama could make Mahatma Gandhi so great, so pure, so honest and so divine, should it not be possible to take another limb of Yoga — Asana — and through it reach the highest goal of spiritual development?

In a note in 1959, cited in an article by Karl Baier, Iyengar said,

‘In each posture, in each action, you should be able to find yoga in its integrity according to Patanjali’s explanations’ -at which time Iyengar undertook a first attempt to rediscover the whole eightfold path in Asana.

Later, in 1970, in Iyengar’s words…’

‘Patanjali has not said: ’Eight steps;’ all these put together are Yoga. But unfortunately people who have not practised at all say: ‘This is physical’. Yama and Niyama: when you are doing the posture, the ethics of the right foot, the ethics of the left foot, are they even or not? If you let loose, that is untruth. If the palms are not joining (Parsvottanasana), that is Himsa: you are showing violence on that palm which is not working at all. Because your intelligence has not touched there, so the truth is unknown. […] So please learn that these poses have been given to know whether in any posture whatever we do, whether you can follow the eight steps or not. […] All the postures contain all the eight steps’

These references to using the practice of asana as a vehicle to undertake a svadhyaya and examine the consciousness.

Yogic knowledge – Knowledge from experience

The culture within a school develops out of the explicit and implicit messages delivered to students. If only class attendance is offered, this values a technical and instructional approach to practice. It tends to value the teacher’s knowledge highly and the student aims to replicate these details within their own practice.

As a self-study, however, students need to be inducted into the practice so that a competence in techniques and details whilst significant form the vehicle (catalyst) through which to study their own experience and examine the behaviour of the Citta. In such a setting the role of practice becomes central to the learning paradigm. We attend classes to gain techniques and details but ultimately we learn through a practice.

A school is an avenue for coming into contact with a practice. It can also become a place for students to participate in a practice culture and can form an intermediate step and support of one’s own home practice.