This is a topic which up to now, in my experience, has been little discussed. Yet it is something that will affect all long term yoga practitioners, with a little bit of luck. The subject is perhaps only emerging now because we are the first full generation of practitioners to go this far, people with 30 or 40 years of practice behind us. That, by the very nature of things, signifies dealing with age.

It may also be that we are only now, coerced somewhat by our bodies, beginning to face up to the reality of ageing, to look squarely and truthfully at what is happening. We are obliged by this new reality to see what options there might be, ones that don’t lead us to stop practising. After a life of yoga this hardly even seems something to consider. However, truthfully, some inner conflict does often arises.

The first important question: what changes with the passage of time?

The answer: nothing, and everything.

Nothing, because practice is practice. It is always about whoever and however you find yourself on any particular day.

Everything, because your body may now place persistent obstacles in your path, and new doubts can arise.

What should I now be practising? How to go forward despite the new restrictions? What is my practice to be today, what will it become in the future?

The Early Years

Let’s go back a bit, to the early years.

Some of us started young, at 26 for me. The obstacles at that stage, for me, were more of a mental nature. The bodywork was tough and demanding, but I would rest and be ready for more. It was hard, but perhaps its very toughness made it also exhilarating.

It was my mind that was more challenged, and this proved to be confronting.

A few examples:

Accountability: Surely my difficulty in the poses today was someone else’s fault. Other students were distracting me with their chatter, or by their movements. The idea that it was me that was the problem took a while to accept. I wasn’t used to shouldering responsibility for what was happening in that way.

Consequences to my actions: A late night, too much dinner, other demands on my time. What could I do but go with those pulls? Did I have a choice? Ok, maybe I did.

Other people’s perceptions or thoughts on my practice: family and friends sometimes didn’t understand that yoga was important to me. Should I be more flexible and not insist on some practice time?

Answers to these problems started to emerge by themselves, through regular, daily practice. Some things just started to become clearer, more defined. In some ways, they had to, because the same issues kept occurring, and I also kept practising. Eventually, it became clear that I had to explore some new ways to resolve these conflicts, and I had to try a few new approaches to how I went about things in life off the mat too.

So maybe, just maybe, my dropbacks were not coming badly because someone started talking in the room. Perhaps it was up to me to find a better technique or to learn to keep my mind more focussed regardless of what else was going on around me.

It was just possible that if I chose not to stay up so late, or to modify my food on certain nights, or to take better care in how I scheduled events, I would feel more prepared for yoga the next day. I did have some control over how my day was set up.

And over time friends and family, with a bit of compromise on both sides, began to see and respect what yoga was doing for me. If I was clear and persistent enough not to give in to the pulls and doubts that would arise each day, other people in my life saw that it was possible to effect change and that yoga practice was just something different, not something negative. Some who were close enough could see that the effects of yoga could be positive for family relationships too.

These examples are relevant because that early practice, with all its challenges, taught me a lot. It allowed me to use my youthful energy to give my mind time to mature. Refining my body with the aspiration of doing better physical poses kept me occupied while my mind developed more clarity and while my understanding progressed a bit further. Practice was changing me, while I was caught up with the physical. This, I might add, can happen at every age. Youth was helpful, but it was not essential. I have seen this same process occur for anyone who allows themselves to properly surrender to the possibilities offered by practice, who does not allow uncertainty and inner disbelief to stop them from doing something.

Physical Obstacles

Now, with age, I find that the initial problem is almost the reverse.

The mind is more flexible, more willing, and able to reflect and to observe itself, and the body is meeting a range of obstacles. It doesn’t recover so easily, it protests more, it is more difficult to negotiate with.

This gives rise to new mental challenges: is practice as I have known it all over from here on, now that certain movements, outer forms, are no longer coming or possible? Am I still really practising?

I can say that, for me, there has been a certain time of grief involved. When I started facing some significant restrictions, I felt like I was losing a part of myself that had been me for 30-35 years. This was something that couldn’t be “fixed”. This wasn’t just going to go away through a good night’s sleep, or a bit of remedial work. This was here to stay. And just as when I was younger, I found the whole idea of facing these challenges to be confronting. And I wasn’t sure what to do.

Should I just give up on certain poses, or keep trying, despite the new reality my body was experiencing?

Should I even practise at all when I have these body “problems” going on?

Is my practice now meant to be mainly therapeutic, or can I still explore new possibilities through yoga?

What happened anyway? What has caused this change? If I had just done things better, would this not have occurred?

For example, I have a hip problem, what did I do wrong? And it’s not just me asking myself this question. Students and other practitioners are quietly wondering that about their teacher or colleague too.

And as yoga teachers we might even experience a little shame: somehow we were meant to be better, almost omnipotent, not succumb to the usual age-related body “deterioration”.

It’s time to get real.

From perhaps 50 or so onward, a number of problems may arise.

Some examples:

- Menopause and its changes

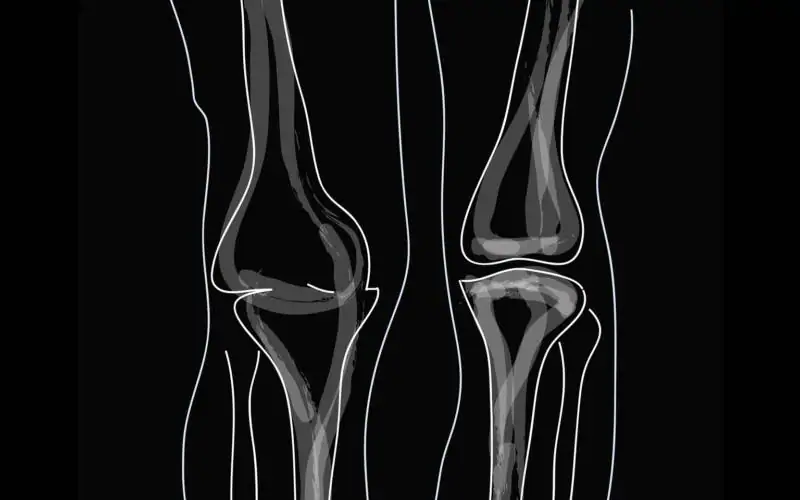

- Arthritis, familial, through old accidents, through the ageing process itself. It may be mild or highly restrictive. It is actually much more of an issue than I personally imagined. But I had thought: that won’t happen to me, I do yoga. Other people said the same thing. Not you…

- Mental health changes, with depression and anxiety for some. Memory loss.

- And actual life-threatening health issues such as heart problems, cancer, etc as well.

We are however thankfully not robots and, in any case, they wear out too. The changes we experience as humans are also useful for our maturity. They force us to think differently and to observe ourselves more closely. We have to become more mindful just to keep doing what we are used to doing. It is important to neutrally just observe what is happening, to identify the problem, not react emotionally, or at least not leave it at that.

The body is mortal and problems arise due to:

- The nature of the human body

- Genetics

- Physical or mental traumas

- Life changes, as in the death of parents, friends, other family members

- The plain inexplicable

Openness to Change

From where I stand, it’s really not over yet.

Here are a few things I have found in the last ten years:

Firstly, keep practising. How will we know if yoga can help if we stop?

There are immense benefits to be found once we identify the nature of the obstacle, accept its existence, and then start learning how best to work with what we find, to manage it. What helps, how to create space in a restricted hip, how to lift a depressed mind.

If we can just be open to change it also may offer unknown possibilities. It might be more helpful to be willing to see what is there rather than deny it, as it has already happened anyway and will likely continue. There is learning in that part of the process if we can keep being open to practising and to explore.

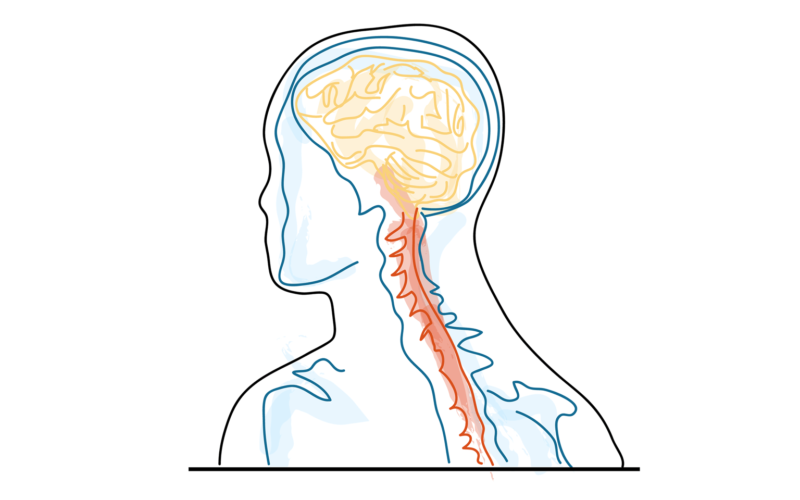

One day in Pune Guruji was working with a young paraplegic man. He said to me in the medical class that he wouldn’t know how much change could occur, how much the nerves would respond until he worked with him closely and observed how the man’s body and mind responded.

If pain or restriction persists, we are not necessarily doing something wrong. It may be that we are just not recognising what is currently going on, some shift that has already occurred somewhere inside and that is having an effect on our body, and our mind.

It’s helpful to become more observant. We have to be, so that we can watch out for new causes and effects, what is working and what is not working, what is helpful and what is irritating things further. It is useful to be able to objectively observe both the good effects and the bad, like a scientist.

Finding an Intelligent Approach

Some poses which seemed to be lost may still return, perhaps in a different way, and only if we really grasp the best way into them, if we can apply a more intelligent approach.

I have seen that I sometimes find an angle into the pose that had been missing all along. We start to look at familiar asana with new curiosity.

It is no longer a case of seeing how to just attain the pose, but rather finding out what we can learn that allows us some access, some freedom within the restrictions. We can create new space and find some vitality in the stiffer places. Perhaps something like the image of bringing wetness to the dry areas, as Guruji spoke about. I often think it is like threading a needle. We have to be very precise, specific and clear in each action to gain maximum effect and opening. This becomes a very absorbing way of approaching practice and one that can show us a path to follow, rather than pushing our way forward.

Past experience is also useful. It can guide us if we let it not dictate from the nostalgia of remembering how we used to do things. It is a glimpse of possibilities that may still exist, though perhaps in a different form. It’s more like “I know practice can shift my understanding because it has done that before”.

Importantly, having one right way to do things is often a real hindrance.

On a practical level, how much should I press forward today? Each day can be very different. Finding out what ingredients I have to work with today is more effective.

I have learned to not avoid things permanently. I try to look at other more useful ways to do something. This may require supports, and maybe not. This is ultimately not different from everyday practice, right from the very beginning of yoga. It is always a question of finding appropriate actions. We are just not that prepared or mature as Beginners to always see this. It is where older new students often fare better.

We get back to the fact that it is the mental obstacles that may require more of a push, and it is important to remember the benefits of getting on the mat. If we do that a few times, we may recognise how much it can help. That is motivating. And here past experience is again useful.

Aims of Practice

What is the aim of practice anyway?

A few possible thoughts:

- To still the fluctuations of the mind

- To find a balanced state conducive to bringing us to reflection and observation.

- To provide us with a tool for living. How best can I manage this situation and see what the best way forward is.

- To take charge of ourselves and to keep exploring in ways that respectfully bring about a mental and physical change in ourselves.

- To maintain freshness and clarity in body and mind, an inner vitality.

These aims are ageless. Ongoing practice can help us achieve our fullest and best potential.

Yoga offers us the chance to be the best that we can be at any given time, whatever the circumstances.

Why would we stop doing that?