Pranayama is the art of breathing according to yoga principles and techniques. It is the beginning of the more inward journey on the path of yoga. A subtler, more refined form of self-awareness and exploration is both developed and required for its practice.

Often ignored by Western adaptations of yoga that only emphasise asana (posture) practice, pranayama is one of yoga’s most ancient arts, probably dating back more than four thousand years to yoga’s very origins. Written two thousand years ago, yoga’s most important historical text, Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, describes the practice of asana in such a manner as to suggest that, at that time, asanas were seen as a necessary preparation for pranayama, but not widely practised for their own sake.

Pranayama is a practice even more subjective and personal than that of asana. In some ways, no one can really teach pranayama. As teachers, we serve as guides, providing reference points and techniques for pupils to use as they experience the breath and its effects when channeled according to yogic techniques. Pranayama is both outwardly quiet and abstract, as well as inwardly precise and powerful. It is a long and challenging voyage, which involves a different approach from asana (posture) practice. Whereas the postures can initially make use of willpower and determination, pranayama cannot be done with strength or force.

If this sounds a little daunting and perhaps excessively mystifying, remember that most classical yoga texts suggest that the practice of pranayama is only to be undertaken when the yoga postures have been mastered and under the guidance of an experienced teacher. In turn, sustained practice of pranayama over many years is an element of, and a preparation for, the art of dhyana or yogic meditation.

This runs somewhat contrary to the modern Western concept that everything should be available to everybody at all times. Most yoga schools receive frequent phone calls from people with no previous yoga experience, asking if they offer lessons in pranayama and meditation and if not, why not.

The Path to Pranayama

The Iyengar tradition takes a classical view of yoga breathing and meditation. According to Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, these aspects of yoga come as later stages in the eight steps, or limbs, of yoga. First, an understanding of the yoga postures must be achieved through keen and conscious practice to refine the senses and hone the body and mind into more perceptive instruments of self-observation.

In earlier, more rigorous times in India, aspiring yoga practitioners first had to demonstrate worthiness as a pupil before being taken into an apprenticeship with a teacher. The Hatha Yoga Pradipika (1.16) discusses certain habits that undermine yoga practice: over-eating, over-exertion, useless talk, undisciplined conduct, bad company, and restless inconstancy. The Yoga Upanishads mention other obstacles, including bad physical posture and self-destroying emotions such as lust and anger, fear, greed, hatred, and jealousy.

Asanas help explore concepts of stillness and inner action, focus and reflection, firmness of body, and alertness and steadiness of mind, which are all essential prerequisites for the practice of pranayama. If we were learning to play a musical instrument, we would start with the foundational skills and progressively learn more difficult techniques. More complex pieces would be unavailable to us until we had reached a degree of accomplishment in the basic forms. Some music teachers will not allow their students, however gifted, to play certain passages until they are mature in age and/or mental and emotional development. A good yoga teacher will exercise similar restraint with their pupils by first teaching a foundation of posture, body awareness, and stability before introducing work with the breath.

Today, many yoga schools, including those teaching the Iyengar tradition, understand that mindful practice of asana becomes a major factor in creating the discipline, personal ethics, energy, and firmness of intention required to move further along the path of pranayama to inner awareness. In Light on Pranayama, B.K.S. Iyengar writes, “as an earthen pot is baked in a furnace, so should the body be baked by the fire of asanas to experience the true effulgence (efficacy) of pranayama.”

How then does one begin to overcome these common habits to make our way along the path of yoga?

To begin pranayama, he says, we must first learn how to move the intercostal muscles (rib-cage muscles) correctly, as well as the pelvic and thoracic diaphragm, by practising the relevant asanas that bring elasticity to the lungs. Consistent, extended performance of the asanas in all their variations keeps the nervous system clean and clear, thus aiding an uninterrupted flow of energy (prana) while doing pranayama. If health is a balance between mind, body, and spirit, then the practice of yoga postures can help to eradicate physical ailments and mental distractions, thus clearing the way for the spirit.

The Challenge of Pranayama

Yoga as a system is perhaps unusual, if not unique, in that its practice both highlights the mental and physical problems that are hindrances to our progress, and provides us with the very tools we need to overcome them. The second chapter of the Yoga Sutras is a practical outline of how, despite our human frailties and imbalances, we can use yoga to refine our intelligence and move beyond the self-limiting, habitual illusions and tendencies of everyday life to embrace a more unified understanding of ourselves and our relationship to the world around us.

The postures in yoga are indeed a means of using our body to discover our inner selves. They provide us with the outer frame, the tangible and visible form, and a structure to work with. The mind is more elusive and harder to know. It can deceive us so that we believe what we want to believe, such as convincing ourselves that this is the best we can or should do.

But do we actually need to add a subtle and complex subject such as pranayama to our daily routine? Is asana perhaps enough?

The body, on the other hand, is like a canvas on which we can express ourselves as we are right now, and on which we can see the results of our actions. A leg is straight or bent; there is no question of confusion there. We are balancing or not. We are on our mats or off having coffee. Asana practice is relatively straightforward and an uncomplicated method for helping us to see who and how we are. Only then is change possible.

Pranayama is harder to grasp and requires another approach. By using the skills of focus, reflection, stillness, and refinement that we have begun to acquire through posture work, pranayama begins the journey inwards, when our minds and emotions can be seen more clearly. It can never be approached with force or physical strength. If we use hardness, it slips further away.

It is like a story I once heard of a method used by a bioenergetics teacher many years ago. He organised a competition between two businessmen by connecting them with wires to two model electric trains. The trains were set up in such a way that the more relaxed their drivers became, the faster their alpha waves would make the carriages go. The more they tried to win in the traditional way, the more the trains slowed down. The breath is very similar.

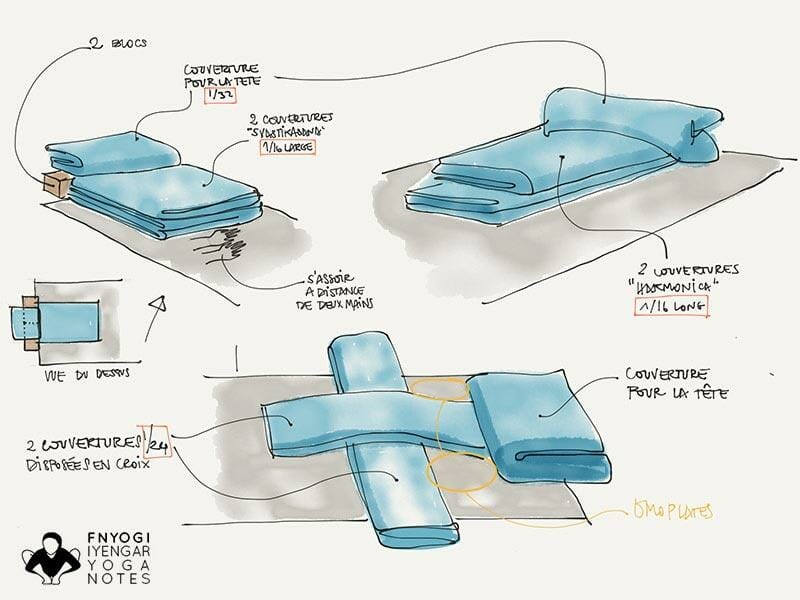

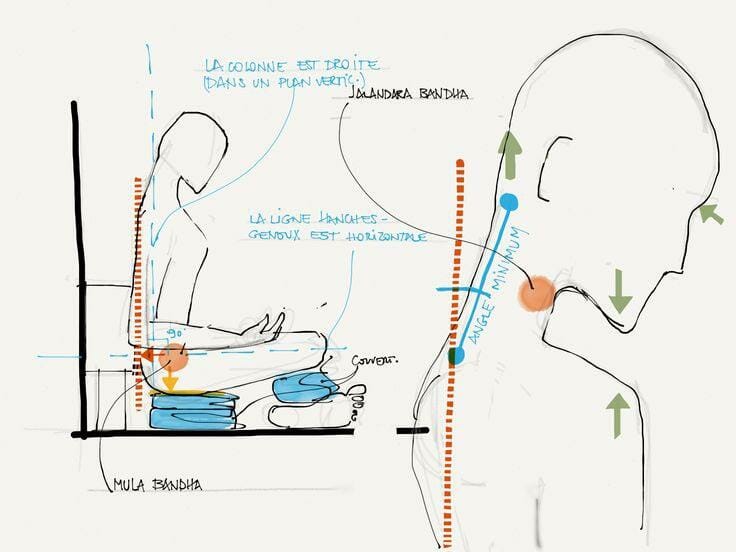

Foundations of Pranayama Practice

The simple essence of pranayama is described in the Yoga Sutras (2.49) as the controlled intake and outflow of breath in a firmly established posture. Breath regulation is important because when the breath is irregular, the mind wavers; when the breath is steady, so is the mind. But the practice of pranayama must be undertaken with caution and respect. The classical text Hatha Yoga Pradipika says that as the lion, the elephant, and the tiger are tamed gradually, so also the breath must be tamed, else it can be harmful to the sadhaka (practitioner).

Normal breathing in our everyday activities is irregular, sometimes described by B.K.S. Iyengar as a zig-zag breath. It moves in different parts of the lungs at various rhythms according to what we are doing, what position we are in, our mental state, the condition of our lungs and diaphragm, and so on.

But pranayama is more than just deep breathing; a pranayama breath must be regulated, steady, evenly prolonged, channeled, and conscious. Pranayama consists of an intentional, long, sustained, and guided inhalation, exhalation, and retention (holding of the breath). It not only enables the body to receive an abundant supply of oxygen but prolongs and channels this air and energy throughout, so that the body may savour and fully benefit from the breath in every possible cell. The conscious regulation and expansion of the breath brings discipline and focus to the mind.

To even begin to observe and know our own normal breath and its patterns takes time and continued practice. Our breathing patterns are deeply habitual and strongly connected to our emotions. To be able to adjust that breath and transform its rhythm, length, and path at will, without tension or struggle, and with our bodies tuned and open to cooperate and synchronize with it, is an intricate, delicate, and challenging task. B.K.S. Iyengar once said that anyone with less than 12 years of regular pranayama practice was still at the raw beginner stage.

Benefits of Pranayama

I used the word daunting at the beginning of this article. Yet the rewards are great, and changes do occur a long time before the 12-year mark. Like pranayama itself, the results are subtle and not as obvious as the transformations that can be observed in our bodies through the postures. It is something that occurs on an almost organic level, outside of our desire for instant gratification.

When I first started pranayama, I just did a very simple form based on becoming aware of the breath and trying to coax the inhalation and exhalation to be more even in length and quality. I did perhaps 15 minutes a day for about a year. I was not aware of any great difference, but I practised because the people I was living with all did. At the end of that year, I traveled for a few days and didn’t do any pranayama during that time. Only then did I notice how different I felt without it. It was its absence after a longish period of consistent, basic practice that made me aware of its many benefits. So simple and quiet were the changes that I had not noticed them at first, yet these initial small modifications also laid the foundation for other, deeper transformations in the way I felt and thought. In my experience, the most profound benefits of yoga take us by surprise with time. They are often not the ones we set out to achieve.

The breath connects our inner world with the outer; it brings our core in contact with the universe outside. It is an inbuilt form of giving and receiving which has an ancient, primordial quality, like the rhythm of the sea. Something always there, but something rarely felt or noticed. It is worth spending some time with, and it is worth preparing ourselves for.

If you are beginning to practise in the Iyengar tradition, expect to spend many months on foundational asanas for the body before you hear your teacher mention pranayama. However, in each class and in every practice, you will be learning something useful to prepare for it.

In a subsequent article, I will describe some of the more specific postures and techniques we use in our classes for students with a minimum of one year’s yoga experience to prepare for pranayama proper.