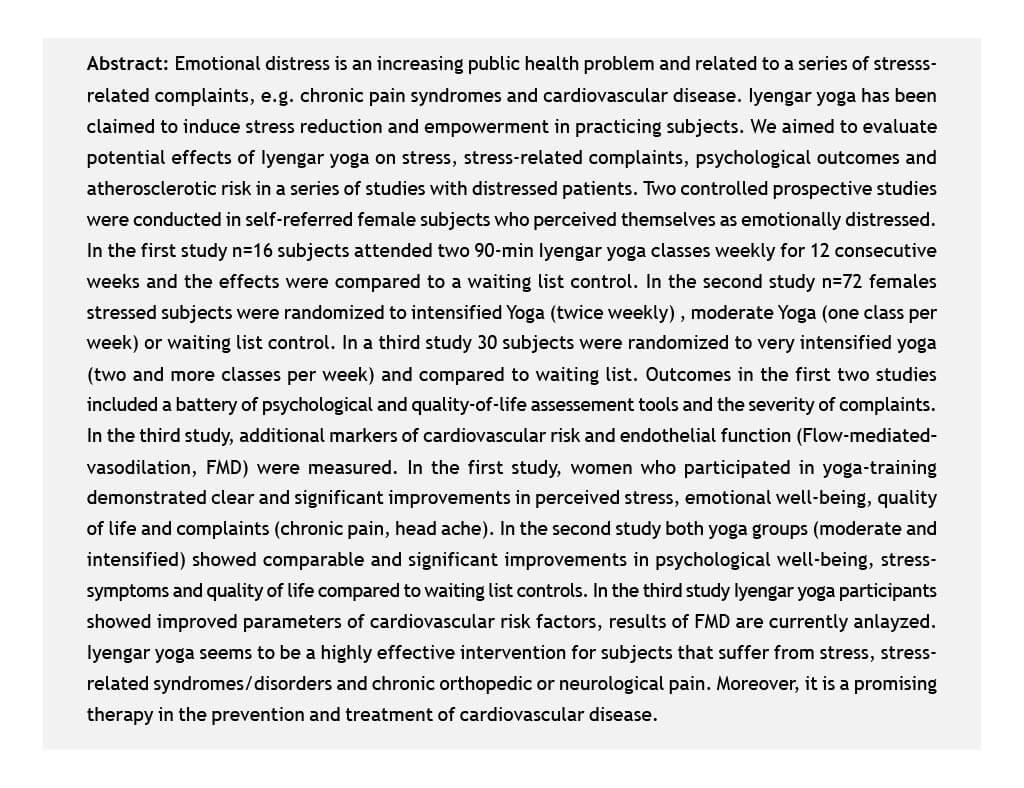

Large numbers of Americans and Europeans have recently adopted the practice of yoga for its proposed health benefits. By 1998, an estimated fifteen million, mostly female American adults, had used yoga at least once in their lifetime, and 7.4 million reported practicing yoga during the previous year. Featured in the lay press yoga continues to be marketed as a method to empower well-being and to reduce stress (“Power-Yoga”). Indeed, some health professionals refer their patients to

Yoga teachers for help in managing a variety of stress-related ailments. Of the many styles of yoga taught in the US and Europe, Iyengar yoga is the most prevalent (2) and promising regarding its clinical efficacy. It is based on the teachings of the yoga master, B.K.S. Iyengar, who has applied yoga to many health problems, using a system descending from Ashtanga yoga.

A number of controlled studies exist on the effectiveness of yoga. These investigations include such conditions as osteoarthritis, carpal tunnel syndrome, multiple sclerosis, bronchial asthma, hypertension, irritable bowel syndrome, mild depression and lower back pain. Five of these studies evaluated Iyengar yoga and reported positive results. However, little is known about the putative impact of Iyengar yoga on distress, stress-related disease and cardiovascular risk. As recent research has emphasized the negative impact of mental distress on health, e.g. cardiovascular health, we undertook a series of studies to examine the clinical effects of an 8- to 12-week Iyengar yoga program in distressed subjects with stress-related disorders and cardiovascular risk.

Methods

Two controlled prospective studies were conducted in self-referred female subjects who perceived themselves as emotionally distressed. The first study is separately published (Michalsen et al., Medical Science Monitor 2005). In brief, n=16 subjects attended two 90-min Iyengar yoga classes weekly for 12 consecutive weeks and health-related effects were compared to a waiting list control.

In the second study n=72 female stressed subjects were randomized to intensified Yoga (twice weekly), moderate Yoga (one class per week) or a waiting list control. In this study we aimed to test the efficacy of Iyengar yoga on stress-related complaints and diseases, and to evaluate if this form of yoga is only effective if practiced on a high-intensity level.

In a third study, male and female 30 subjects were randomized to an intensified Iyengar yoga program (two and more classes per week) and compared to waiting list.

Outcomes in the first two studies included a battery of psychological and quality-of-life assessment tools and the severity of complaints. Moreover, levels of salivary cortisol were measured before and after yoga classes, and, before and after the 3 month programs. In the third study, additional markers of cardiovascular risk (blood lipids, blood pressure) and endothelial function (Flow-mediated-vasodilation, FMD) were measured.

Results

The results of the first study are reported separately (see Michalsen et al. 2005). In brief, the great majority of women who participated in yoga-training demonstrated clear and significant improvements in perceived stress, emotional well-being, quality of life and complaints (chronic pain, head ache) leading to very high effect sizes of Iyengar yoga regarding the overall health effects.

Iyengar yoga induced improvement of depression and anxiety scores up to 50% and 30%, respectively, well-being improved by 65% and sleep by 50%, together indicating a substantial effect of this yoga form on psychological outcome. Moreover, cortisol levels dropped significantly after a 90 min Iyengar training class.

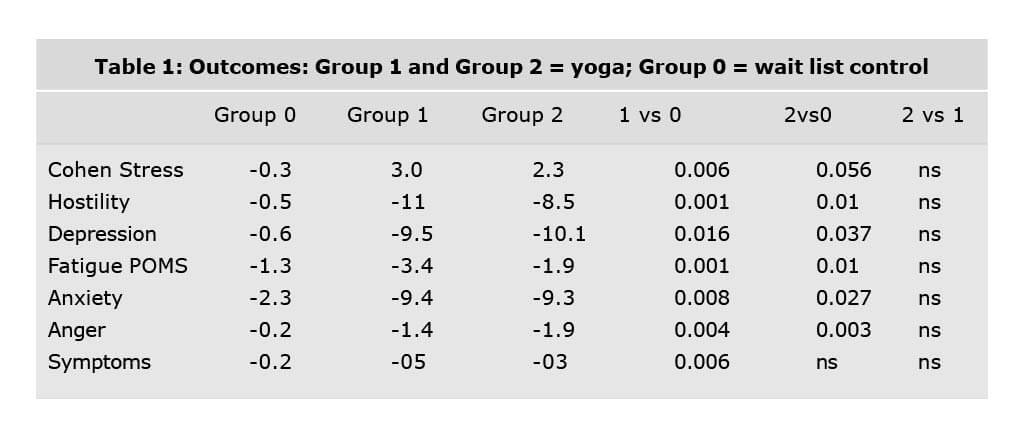

In the second study both yoga groups showed clear and highly significant improvements of quality-of-life, body symptoms as back pain, headache or sleeping disturbances. Specifically, perceived stress (Cohen Stress Scale), hostility, depression, fatigue (assessed by profile of mood states, POMS), anger, and a global score of health symptoms were significantly improved in both groups compared to a waiting list control group. Between the two yoga groups we found no significant differences. However, also the group that was scheduled to have only one 90-minute Iyengar Yoga class per week started to practice yoga several times a week at home. Therefore, training differences between both yoga groups were not as great as preplanned. The results of the specific questionnaires of this study are summarized in table 1.

Finally, there were no adverse effects associated with yoga practice for all subjects and the majority of subjects wanted to continue with Iyengar yoga.

In the third study we found a significant decrease of blood pressure and heart rate after an 8-week high-intensity Iyengar yoga training. Blood lipids were not altered. Results of endothelial function are currently analyzed.

Conclusions

The demonstrated marked reduction in perceived stress and related anxiety/depressive symptoms and the improvements of quality-of-life, cardiovascular risk factors and general wellbeing in our yoga practicing participants are of clear clinical importance. In view of its safety and low costs, further research should evaluate the value of Iyengar yoga for the prevention and treatment of disease, e.g. stress-related disease and cardiovascular disorders.

This article is part of the collection of studies published as the Mumbai Research Compilation. A collection of presentations made at the Light on Yoga Research Trust in collaboration with the Bombay Hospital Trust, Indian Medical Association, General Practitioners Association and the Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder Society. They organized the conference on the “Scientific evidence on the Therapeutic Efficacy of Iyengar Yoga”. It highlights research papers on Iyengar Yoga and its medical benefits. The objective of which being the dissemination of knowledge about the science of yoga in the medical setting. The conference was held on October 12, 2008.