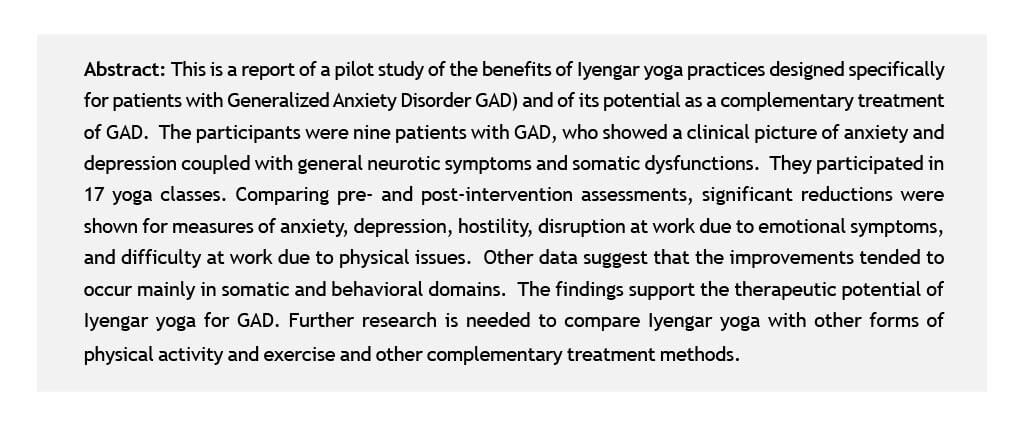

In 2004, a systematic review was conducted of the evidence for the effectiveness of yoga for the treatment of anxiety and anxiety disorders (Kirkwood et al., 2005). Positive results were reported in eight studies. The authors of the review concluded that because of the diversity of anxiety conditions treated and the poor quality of most of the studies, it was not possible to say that yoga is effective in treating anxiety in general. They also suggested that further well conducted research is necessary, particularly if focused on specific anxiety disorders. In a previous study of Iyengar Yoga as a complementary treatment of major depressive disorder, we found that clinical measures of both depression and anxiety were significantly reduced from pre- to post intervention (Shapiro et al., 2007). This is a report of the findings of a pilot study of Iyengar yoga as a complementary treatment of patients specifically diagnosed with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD).

Methods

Participants

The participants who volunteered for this study were patients of the UCLA Anxiety Disorders Clinic, A. Bystritsky, Director, with the primary diagnosis of GAD in the mild to moderate range. Those with other serious primary psychiatric conditions such as major depression, bipolar disorder, or psychosis were excluded. Also excluded was anyone with physical conditions that would limit their ability to participate fully in the yoga practices. Participants with prior yoga experience exceeding three months were also excluded.

Eleven patients volunteered of whom 2 decided not to participate for non-study reasons. The 9 participants included 7 women and 2 men; age, 32.9 yrs. (23-54) (mean, range); education, 18.3 yrs. (14-28); marital status, 5 single, 3 married, 1 divorced; occupation, 4 students, 1 teacher, 1 writer, 1 editor, 1 analyst, 1 sales; medication, 7 of the 9 were on anti-anxiety or antidepressant medications; duration of medication use, 44 mos. (0-132); 5 reported other health problems (chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia, colitis, migraine).

Procedure

17 1-hour Iyengar Yoga classes (3/wk) were led by three highly experienced and certified Iyengar yoga teachers (Marla Apt., Paul Cabanis, and Jim Benvenuto). Attendance was erratic, from 5 to 16 classes; most participants attended 8 or 9 classes (attendance: 5, 8, 8, 8, 9, 9, 9, 13, and 16).

The yoga asanas and sequences were designed specifically for anxiety under the guidance of B.K.S. Iyengar. Each session included inverted postures, supported backbends, supine poses and supported forward bends. The teachers emphasized relaxing regions on the body that are prone to tension as a result of anxiety. The backbends focused on stretching the abdomen where there is often tightness associated with anxiety. In all poses, close attention was paid to the position of the head and neck so that the back of the neck was elongated and the facial muscles (where concentrated tension is associated with anxious thinking) were relaxed and allowed to spread. The participants in the study were taught how to relax the eyes, forehead and throat to help calm the mind. The participants were also taught simple pranayama (breathing) techniques that focused on soothing an overactive mind through attention to and lengthening of the exhalation.

Measures

Assessments were done pre- and post-intervention including: diagnostic interview (MINI, pre-yoga only), Sheehan Disability Scale, Hamilton Anxiety (Ham-A) and Depression (Ham-D) Scales, UCLA4D Anxiety Scale, Cook Medley (CM) Hostility Scale, Spielberger Trait Anxiety (STAI) and Anger Expression (ANGIN, ANGOUT) Scales, Marlowe-Crowne (MC) Social Desirability Scale (defensiveness), Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (QIDS), SF-36 Fitness Scale, Symptom Check List-90 (SCL). Before and after each yoga class, participants rated 20 moods, representing positive, negative, and energy/arousal related emotional states.

Results

Initial data

Ham-A 15.7 (9-23), Ham-D 12. 7 (9-19), UCLA 4D Anxiety Total 50.8 (28-69). These scales were inter correlated: Ham-A-Ham-D .81, Ham-A – UCLA4D .67, Ham-D – UCLA4D .63. All three scales were positively correlated with CM, STAI, SCL, QIDS, and Sheehan Family disability (emotional problems affecting family) scores and with reported caffeine use and smoking, and negatively correlated with several SF-36 fitness scales (general health, mental health). In general, the pattern is one of anxiety and depression coupled with general neurotic symptoms and somatic dysfunctions.

From pre- to post-intervention, significant reductions were obtained in the means of Ham-A, 6.6 (amount of reduction) (p < .02) and Ham-D, 5.6 (p < .005), plus a reduction in CM (indirect hostility) (2.9, p < .02), improvement in a Sheehan scale (less disruption at work due to emotional symptoms) (p < .05) and in a SF-36 fitness scale (p < .05) (less difficulty at work due to physical issues).

In regard to the changes in specific items on the Ham scales, most changed in a healthier direction. The following showed significant effects (ps < .05): On the Ham-A, items 5, 7, 8, and 14: less difficulty in concentrating, fewer somatic complaints (muscular, sensory), and less expressed anxiety symptoms during the Ham-A interview. On the Ham-D, items 10, 12, and 15: less psychic anxiety, fewer somatic (GI) complaints, less hypochondriasis.

As to pre-yoga data predicting improvement, these were assessed by correlating test scores at the beginning of the study with changes from pre- to post-yoga in the Ham scales. Taking all correlations greater than .50, these are the measures associated with improvement: With

Ham-A: higher Ham-A total; SF-36 scales, less bodily pain, more physical health, more vitality; on the Sheehan, less social and work limitations. With Ham-D: the same SF-36 and Sheehan effects plus lower scores on ANGERIN.

As to the mood ratings, significant changes (p < .05) were obtained pre- to post-class on the average over all sessions attended by each participant in 19 out of 20 moods. Positive moods increased, negative moods decreased, and energy-related moods increased. The reduction in Ham-A from pre- to post-intervention was correlated with mean pre- and mean post-session mood ratings per subject. Taking correlations greater than .50, the following post-session moods were associated with improvement in anxiety on the Ham: less fatigued, less depressed, less frustrated, less tired. And before class, participants who rated themselves as less depressed, relaxed, and tired did better. In depression shown in the Ham-D scale for preto post-intervention was associated with the following post-session ratings: less blue, depressed, fatigued, frustrated, irritated, pessimistic, relaxed, and sad. In terms of presession ratings, the following were associated with improvement in the Ham-D: less angry, blue, depressed, frustrated, irritated, pessimistic, sad, sleep, and tired.

Conclusions

The findings indicate that Iyengar Yoga practices designed for anxiety yielded significant benefit for the participants, a small sample of patients with anxiety and depression and other neurotic symptoms and physical complaints. At the end of the intervention, five out of the nine participants would no longer be considered to have the level of anxiety (Ham-A score greater than 7) to be eligible to participate in the study. The remission rate (56%) compares favorably with drug and other conventional methods of treatment of GAD. Excluding the participant who attended only five sessions, the remission rate is 5 out of 8 or 62%.

As to attendance and adherence, unlike our previous research with patients with major depressive disorder, these participants were not as likely to drop out early in the study but they were erratic in their attendance. Only three out of the 17 participants attended more than nine out of the 17 sessions. The poor record of adherence is likely characteristic of this patient group, and we need to consider how to deal with it in future studies.

The clinical and test findings support the potential benefit of yoga as a complementary treatment of GAD. It is of interest that the specific improvements tended to fall into the “somatic” or physical and behavioral domains, not so much in terms of cognitive aspects of anxiety such as “worry.” It also seems that those who were somewhat healthier, physically speaking, and those whose moods were more positive and less negative to begin with did better. Moreover, the participants whose moods improved the most from before to after classes were most likely to benefit from the program.

This was a preliminary study designed to examine the potential and feasibility of Iyengar yoga as a complementary treatment of GAD and to provide a basis for further systematic research. The findings provide evidence in support of its potential for a specific anxiety disorder. We need now to compare Iyengar yoga for GAD with other forms of physical activity and exercise and other complementary treatment methods.

References

- Shapiro, D., Cook, I.A., Davydov, D.M., Ottaviani, C., Leuchter, A.F., & Abrams, M. (2007). Yoga as a complementary treatment of depression: Effects of traits and moods on treatment outcome. Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 4, 493-502.

- Kirkwood, G., Rampes, H., Tuffey,V., Richardson, J., & Pilkington, K. (2005). Yoga for anxiety: A systematic review of the research evidence. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 39, 884-891.

This article is part of the collection of studies published as the Mumbai Research Compilation. A collection of presentations made at the Light on Yoga Research Trust in collaboration with the Bombay Hospital Trust, Indian Medical Association, General Practitioners Association and the Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder Society. They organized the conference on the “Scientific evidence on the Therapeutic Efficacy of Iyengar Yoga”. It highlights research papers on Iyengar Yoga and its medical benefits. The objective of which being the dissemination of knowledge about the science of yoga in the medical setting. The conference was held on October 12, 2008.