Recent surveys point to the increasing popularity of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) (Barnes, 2004), particularly for chronic health and pain conditions that may not respond well to conventional medicine. This increase in CAM use is evident in adult as well as pediatric populations (Tsao, & Zeltzer, 2005). Yoga is among one of the more popular CAM treatments, and estimates suggested that approximately 5% of adults in the US practice yoga (Barnes, 2004). A recent study of CAM preferences for children aged 8-18 years with chronic pain found yoga to be amongst the top three CAM treatments (Tsao et al., 2007). Despite its popularity, limited research has explored the empirical efficacy of yoga as a treatment for chronic pain conditions. This review examines the extant literature that does so, and includes studies on yoga and any chronic health condition associated with pain in individuals across the lifespan.

Yoga developed in ancient India incorporating and uniting principles of posture, breathing, and meditation that are thought to bring physiological and psychological benefits to its practitioners. Characterized as a science of self-development through a series of specific asanas (body postures), pranayama (proscribed patterns of breathing), and meditation, yoga has been embraced in modern Western settings as a form of exercise and a technique for relaxation/stress reduction. Currently, yoga programs are relatively low cost and widely available to the public in the form of classes or at home video/book programs. When performed properly, little risk of adverse effects appear to exist. Nevertheless, there is a dearth of empirical research on the specific effects of yoga for chronic pain conditions.

Yoga, as a discipline, is divided into many branches. Traditionally Hatha yoga refers to the eight limbs of yoga, but is often used to describe yoga practices that deal with the physical body, and emphasize asana and pranayama. Hatha yoga consists of numerous styles, and some are more suited to the safe treatment of chronic conditions. Iyengar yoga is frequently used in studies of yoga for chronic pain. This tradition emphasizes precision in performing poses and individualizes the practice to each participant’s ability and mobility level through the use of props, including blocks, straps and cushions. Iyengar instructors are required to complete extensive training and certification processes.

Because the poses are precise, Iyengar interventions, if detailed appropriately, can be widely and accurately replicated. Hatha yoga styles are varied and the existence of many traditions can create difficulties in standardizing treatment without detailed information about the type of yoga and specific practice employed in studies.

Methods

The effectiveness of search strategies to identify trials using CAM appears to be contingent on the number of databases searched; a variety of different sources are required to identify relevant articles (Pilkington, 2007) . Accordingly, the PubMed, Psych Info, CINAHL and Cochrane Library databases were searched up to November 2007 using the keywords: “yoga” “health” and “pain.” The focus of this article is to provide an overview of data that has been published in peer-reviewed journals regarding yoga treatments for chronic pain. Due to the limited research available, studies were included if they involved randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or repeated measures without a control group (RM) designs. A number of yoga articles have been published in Indian journals, and despite not being widely circulated, where possible these articles were retrieved and included in the analyses. Examination of the literature revealed three main pain conditions that have been treated with yoga. As grouped below, these conditions included musculoskeletal pain, headache/ migraines and irritable bowel syndrome. Results of the studies are presented in tables 1-3.

Yoga for musculoskeletal conditions

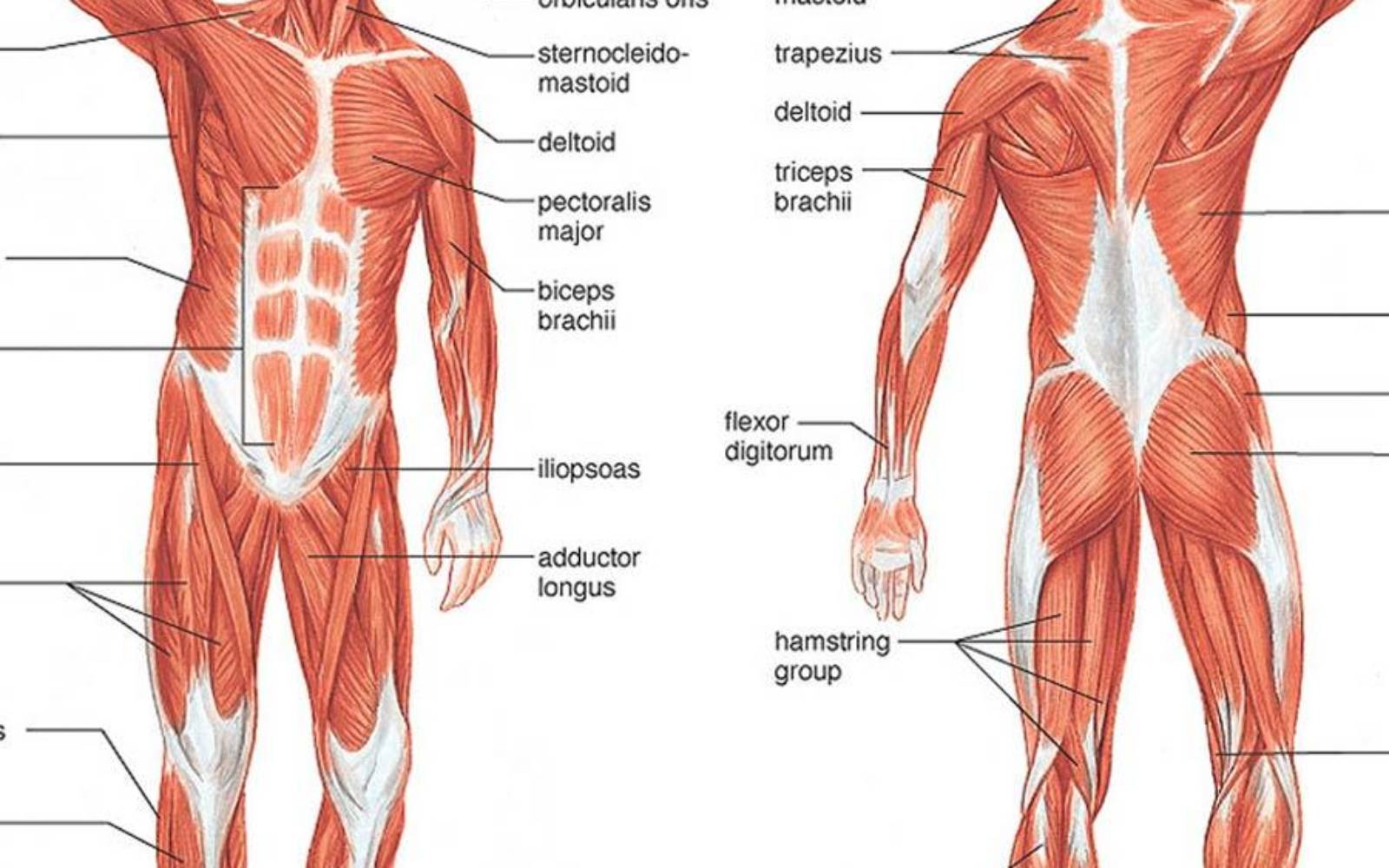

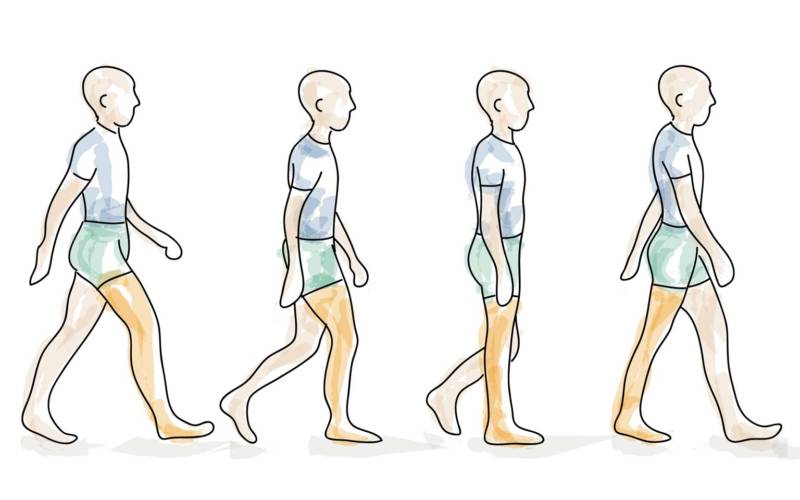

A number of studies have examined the impact of yoga on musculoskeletal conditions and in particular, various forms of arthritis. Most studies have focused on older populations, with few including children, adolescents, or young adults. One study in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients did include adolescents and young adults but the age range was so broad that extrapolating the findings to specific populations is difficult (Haslock et al., 1994). Despite the small number of participants in this study (n = 10), in each of the yoga and control groups, yoga was found to improve hand grip strength significantly. Hand grip strength was also significantly improved in 20 RA patients following yoga training compared with controls (Dash & Telles, 2001). Garfinkel and colleagues tested Iyengar yoga for patients with osteoarthritis of the hands (Garfinkel, et al., 1994) and carpal tunnel syndrome (Garfinkel et al., 1998). Both studies resulted in the amelioration of pain and improved mobility. The efficacy of Iyengar yoga for osteoarthritis has further been demonstrated by Kolasinski et al (Kolasinski et al., 2005), who found reductions in pain, physical functioning, and arthritis impact in a group of patients with osteoarthritis of the knee. That these studies have included limited sample sizes (as small as seven) yet still found beneficial effects of yoga provides support for the efficacy of yoga for arthritis. Increased strength and flexibility is a recurrent finding across musculoskeletal conditions; improvements in strength and flexibility have also been reported in a study of yoga for older women with hyperkyphosis (colloquially known as “dowager’s hump”) (Greendale et al., 2002). In a general sample of older adults with age related stiffness, Iyengar yoga was found to increase hip extension and stride length, further indicating the flexibility benefits of yoga. These studies used repeated measures designs with benefits reported post-treatment versus pre-treatment. The lack of randomization or controls limits the strength of the findings. It is questionable whether yoga induced improvement or the mere presence of treatment led to increased functioning.

Studies using RCTs have been reported for multiple sclerosis and chronic back pain. Oken et al conducted an Iyengar yoga intervention for a largely female multiple sclerosis patient population. Although the yoga group showed significantly improved fatigue compared with the wait-list controls, the differences between the yoga intervention and an exercise intervention were limited, and no differences were found on mood or cognitive functioning measures. Possibly the condition of the patients deteriorated substantially over the course of the study, which at 6 months is a great deal longer than most other yoga interventions. Health status and disease progression were not controlled in the study. Nevertheless, the findings indicate that yoga is at least as effective as exercise in managing the fatigue of MS, a progressive disease.

A series of RCTs for chronic low back pain revealed mixed results. A six-week hatha yoga class for patients reported non-significant trends toward improved physical and psychological functioning for the yoga group (n = 10) compared with a wait list control (n = 10) (Galantino et al., 2004). The small sample size and relatively short treatment program may have limited the power to detect significant changes. These null findings can be contrasted with two further studies indicating the benefits of yoga for chronic back pain. In 101 patients, a course of viniyoga yoga led to an improved back-related functioning compared with an exercise control group and an education group. At 26 weeks post intervention, the yoga group further demonstrated improved pain levels and functioning compared with the education group (Sherman, et al., 2005). Other positive findings were reported for a similar large group of chronic low back pain patients (Williams et al., 2005). The study found that compared with a control group receiving educational materials on back care, significant improvements occurred in functional and medical outcomes for patients practising Iyengar yoga. Over half the patients experienced significant reduction in pain, over three-quarters reported improved functionality, and nearly 90% reduced pain medication usage. The latter two studies represent some of the largest RCTs of yoga for chronic pain conditions and provide compelling initial support for the efficacy of yoga in treating chronic low back pain.

Yoga for headache/migraine

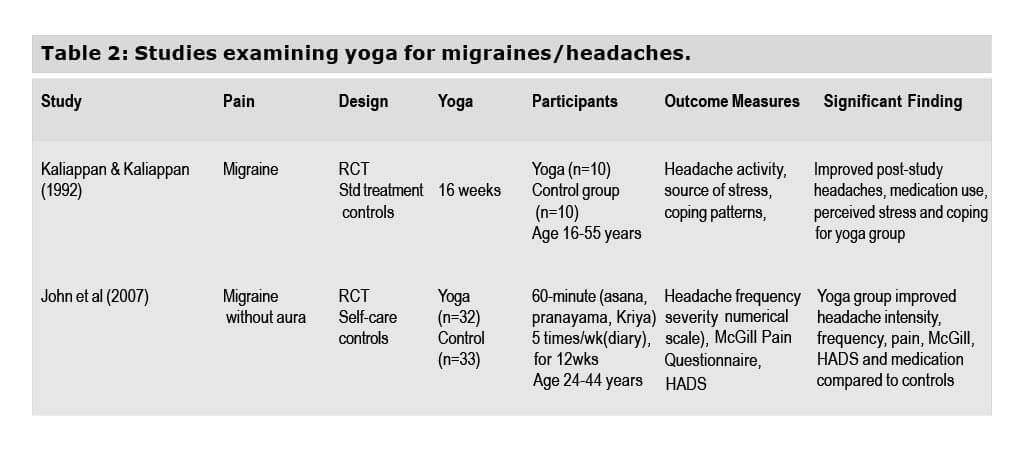

Two RCTs have shown that yoga alleviates the physical and psychological aspects of migraine/ headache pain by improving pain severity and psychological functioning and reducing medication use (Kaliappan, 1992) (John et al., 2007). The first of these studies, conducted by Kaliappan and Kaliappan (1992) was limited by a small sample, a heterogeneous group of “headache” sufferers that included tension headaches and migraines, an absence of standardized pain and stress questionnaires, and a lack of description regarding the yoga practice used. The results are still promising and point to the possible role of yoga as a stress reduction technique and an adaptive coping response in alleviating pain. A larger yoga study conducted for treatment of migraine without aura showed positive benefits (John et al., 2007). Seventy-two patients were randomized to an educational control group or to a yoga treatment the authors termed “yoga therapy” that combined asanas, pranayama, and kriya, a nasal water cleansing process. After the 3-month intervention, patients in the yoga group reported significant reductions in sub-scales of the McGill pain questionnaire (frequency, intensity, and sensitivity of pain, an anxiety and depression scale, and medication use compared with controls). The findings support the role of yoga for alleviating the physical and psychological aspects of migraine pain. Nevertheless, which aspects of the yoga therapy were responsible for the improvement or whether such a combined approach is superior to standard yoga involving only pranayama and/or asanas is not known.

Yoga for irritable bowel syndrome

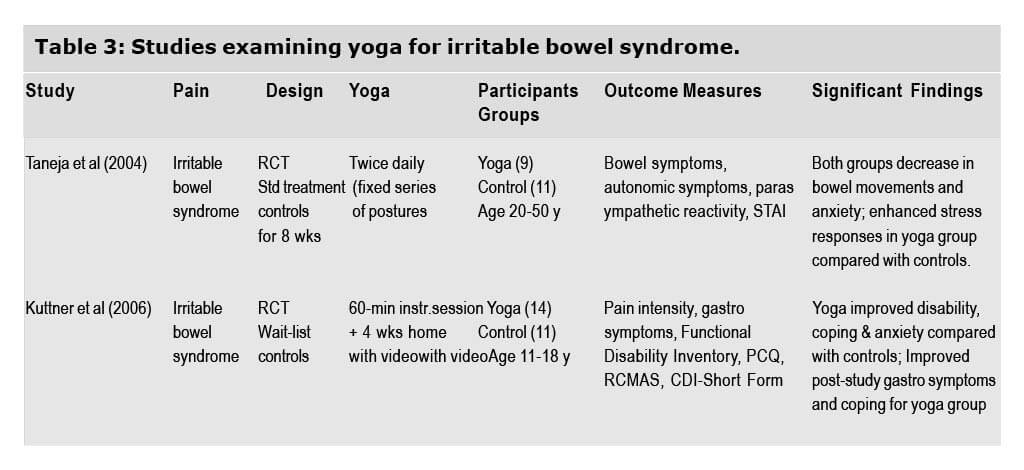

Positive effects have also been found for yoga in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Kuttner et al (2006) provided the only systematic analysis of the use of yoga for pain conditions in children and adolescents (i.e., aged 11-18 years). This limited intervention consisted of a 4-week home practice of yoga, subsequent to an initial training session. To what degree participants actually practiced yoga and to what extent they adhered to the prescribed yoga protocol is unclear. Although the intervention is described as Iyengar yoga, whether a formally trained Iyengar yoga teacher was involved in the intervention and whether the poses taught to children were legitimate Iyengar asanas is unknown. Despite these limitations, Kuttner et al found that the yoga group exhibited significantly improved post study IBS symptoms and significantly improved disability, coping, and anxiety relative to wait list controls.

In an RCT using yoga for IBS symptoms and functioning, Taneja and colleagues (2004) found improved parasympathetic reactivity in a group undergoing biweekly yoga classes for 8 weeks compared with standard treatment controls. One strength of the study was a description of the specific yoga asanas and pranayama used, allowing for replication and critique of the intervention. Both groups improved equally on decreasing bowel movements and anxiety, indicating limited additional benefits for yoga over standard intervention. The yoga group, however, showed significantly decreased autonomic system responses and increased parasympathetic reactivity when compared with controls at the end of the second month of yoga, indicating a decrease in stress responses. Limiting the study is a minimal sample size (n = 9 for the yoga group) and abbreviated health and functioning assessments. Possibly an increase in the study’s power may have resulted in notable differences between the groups.

Discussion

Of the 15 studies reviewed, only one study on chronic pain failed to find significant improvement after a yoga intervention (Galantino et al., 2004). This trial tested a 6-week yoga practice for chronic low back pain and reported non-significant trends in the yoga group (Galantino et al., 2004). These null findings underscore the importance of an appropriate sample size (the yoga group included only 11 patients) and a sufficient length of treatment to induce change. A further limitation relevant to all yoga studies is the lack of a realistic placebo group. Given the scientific, practical, and ethical difficulty in developing a legitimate sham yoga group, studies generally use a standard treatment or wait list control group. It is possible that improvements across studies are the result of patient expectations. Nevertheless, many studies used prior experience with yoga or meditation as exclusion criteria, thus reducing the likelihood of including patients who have strong positive feelings towards yoga.

Among the most important limitations of the existing work on chronic pain and yoga are the (1) inadequate sample size for most of the studies; (2) overly broad age range (e.g., inclusion of adolescents and elderly patients in the same sample); (3) lack of specification regarding the yoga school utilized in most studies; and (4) lack of a theoretical model to inform treatment implementation and assessment of outcomes.

As a great variation is found across the numerous traditions of yoga, this lack of standardization can confound interpretations of the overall efficacy of yoga on illness states. Without a clear description of the yoga tradition and the specific yoga poses used, further research designed to replicate the findings is difficult. We argue that future yoga research should include not only a clear indication of which specific tradition of yoga the intervention follows (i.e., Iyengar yoga, viniyoga) but also a detailed description of the poses incorporated into the program. This approach will afford greater understanding of which asanas are most beneficial for which conditions and will allow other interventions to replicate benefits. Another important dimension that has to be detailed better in studies of yoga efficacy for health conditions is that of teacher qualifications. Certain forms of yoga, such as Iyengar yoga, require extensive training and accreditation. Background information regarding the teachers’ credentials is key to ensuring the validity and reliability of the yoga intervention.

Conclusion

Yoga research suggests that such training benefits pain patients when they follow a program of yoga. Although the improvements on physical symptoms are relatively consistent (e.g., pain intensity, strength, medication use), improvements on psychological functioning scores for pain groups are not as consistent. That said, this result could be a function of the kinds of poses utilized. Other studies looking specifically at psychological functioning and yoga (Woolery, Myers, Sternlieb, & Zeltzer, 2004) demonstrated significant improvements in their population, and the poses in these studies were intended for improved psychological functioning. Possibly, the poses designed specifically for physical and psychological functioning should be implemented if interventions intend to address the entire functioning of the patient.

Generally, yoga is considered a safe practice and one with few dangers to people with health conditions. This aspect has not been rigorously explored, however, and more work is needed in this area to ensure that yoga interventions are indeed safe for a variety of patients. Further large scale RCTs designed to address the safety and efficacy of yoga for health conditions are clearly required before definitive conclusions can be drawn regarding the use of yoga to improve pain and functioning. During the design stage, future studies should also be mindful of employing yoga traditions that involve substantial training in therapeutics. At the least, studies should provide details regarding the yoga tradition and background of teachers used.

At this stage, yoga represents a promising intervention. The practice is low-cost, easily accessible, and poses few, if any, hazards to people with health conditions. As the public is becoming increasingly interested in the use of CAM (Barnes, 2002), the popularity of yoga is likely to continue to grow. Further research is needed to inform health care practitioners regarding the safety and efficacy of yoga for their patients with pain.

References

- Barnes P, P.-G. E., McFann K, Nahin R. (2002). CDC Advance Data Report #343 Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States.

- Barnes, P., Powell-Griner, E., McFann, K., Nahin, R. (2004). CDC Advance data report #343. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Adults. United States.

- Dash, M., & Telles, S. (2001). Improvement in hand grip strength in normal volunteers and rheumatoid arthritis patients following yoga training. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol, 45(3), 355-360.

- Galantino, M. L., Bzdewka, T. M., Eissler-Russo, J. L., Holbrook, M. L., Mogck, E. P., Geigle, P., et al. (2004). The impact of modified Hatha yoga on chronic low back pain: a pilot study. Altern Ther Health Med, 10(2), 56-59.

- Garfinkel, M. S., Schumacher, H. R., Jr., Husain, A., Levy, M., & Reshetar, R. A. (1994). Evaluation of a yoga based regimen for treatment of osteoarthritis of the hands. J Rheumatol, 21(12), 2341-2343.

- Garfinkel, M. S., Singhal, A., Katz, W. A., Allan, D. A., Reshetar, R., & Schumacher, H. R., Jr. (1998). Yogabased intervention for carpal tunnel syndrome: a randomized trial. Jama, 280(18), 1601-1603.

- Greendale, G. A., McDivit, A., Carpenter, A., Seeger, L., & Huang, M. H. (2002). Yoga for women with hyperkyphosis: results of a pilot study. Am J Public Health, 92(10), 1611-1614.

- Haslock, I., Monro, R., Nagarathna, R., Nagendra, H. R., & Raghuram, N. V. (1994). Measuring the effects of yoga in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol, 33(8), 787-788.

- John, P. J., Sharma, N., Sharma, C. M., & Kankane, A. (2007). Effectiveness of yoga therapy in the treatment of migraine without aura: a randomized controlled trial. Headache, 47(5), 654-661.

- Kaliappan, L. K., K.V. (1992). Efficacy of Yoga Therapy in the Management of Headaches. Journal of Indian Psychology, 10(1 & 2), 41-47.

- Kolasinski, S. L., Garfinkel, M., Tsai, A. G., Matz, W., Van Dyke, A., & Schumacher, H. R. (2005). Iyengar yoga for treating symptoms of osteoarthritis of the knees: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med, 11(4), 689-693.

- Kuttner, L., Chambers, C. T., Hardial, J., Israel, D. M., Jacobson, K., & Evans, K. (2006). A randomized trial of yoga for adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome. Pain Res Manag, 11(4), 217-223.

- Pilkington, K. (2007). Searching for CAM evidence: an evaluation of therapy-specific search strategies. J Altern Complement Med, 13(4), 451-459.

- Sherman, K. J., Cherkin, D. C., Erro, J., Miglioretti, D.L., & Deyo, R. A. (2005). Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med, 143(12), 849-856.

- Taneja, I., Deepak, K. K., Poojary, G., Acharya, I. N., Pandey, R. M., & Sharma, M. P. (2004). Yogic versus conventional treatment in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized control study. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback, 29(1), 19-33.

- Tsao, J. C., & Zeltzer, L.K. (2005). Complementary and Alternative Medicine Approaches for Pediatric Pain: A Review of the State-of-the-science. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2(2), 149-159.

- Tsao, J. C. I., Meldrum, M., Kim, S. C., Jacob, M. C., & Zeltzer, L. K. (2007). Treatment preferences for CAM in pediatric chronic pain patients. Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

- Williams, K. A., Petronis, J., Smith, D., Goodrich, D., Wu, J., Ravi, N., et al. (2005). Effect of Iyengar yoga therapy for chronic low back pain. Pain, 115(1-2), 107-117.

- Woolery, A., Myers, H., Sternlieb, B., & Zeltzer, L. (2004). A yoga intervention for young adults with elevated symptoms of depression. Altern Ther Health Med, 10(2), 60-63.

This research was originally published in print on 2008-01-01 and online on 2011-05-04. It is also part of the collection of studies published as the Mumbai Research Compilation. A collection of presentations made at the Light on Yoga Research Trust in collaboration with the Bombay Hospital Trust, Indian Medical Association, General Practitioners Association and the Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder Society. They organized the conference on the “Scientific evidence on the Therapeutic Efficacy of Iyengar Yoga”. It highlights research papers on Iyengar Yoga and its medical benefits. The objective of which being the dissemination of knowledge about the science of yoga in the medical setting. The conference was held on October 12, 2008.

Evans , S., Subramanian , S. & Sternlieb , B. (2011). Yoga as treatment for chronic pain conditions: A literature review. International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 7(1), pp. 25-32. Retrieved 1 Apr. 2017, from doi:10.1515/IJDHD.2008.7.1.25