In the previous issue of Australian Yoga Life, I outlined why some experience of yoga asanas is important before attempting to observe and channel the breath as required for the practice of yoga breathing.

Asana (posture) teaches us focus, awareness, timing, and a degree of patience. These qualities, and others, develop over time as we continue to observe the physical body in practice. We can begin to understand the effect each movement has, the next step to take on the basis of the consequence of the last action. We learn not just to do, but to reflect on what we have done, to be more perceptive about the positive and negative results of our way of practising. In short, we begin to refine our awareness in a very tangible way through the structure of our own body, its muscles, joints, skin. This self-study gives us concrete reference points to which we can connect the mind. Through the cultivation of this consciousness in our physical actions, we can now fruitfully begin to turn our attention inwards.

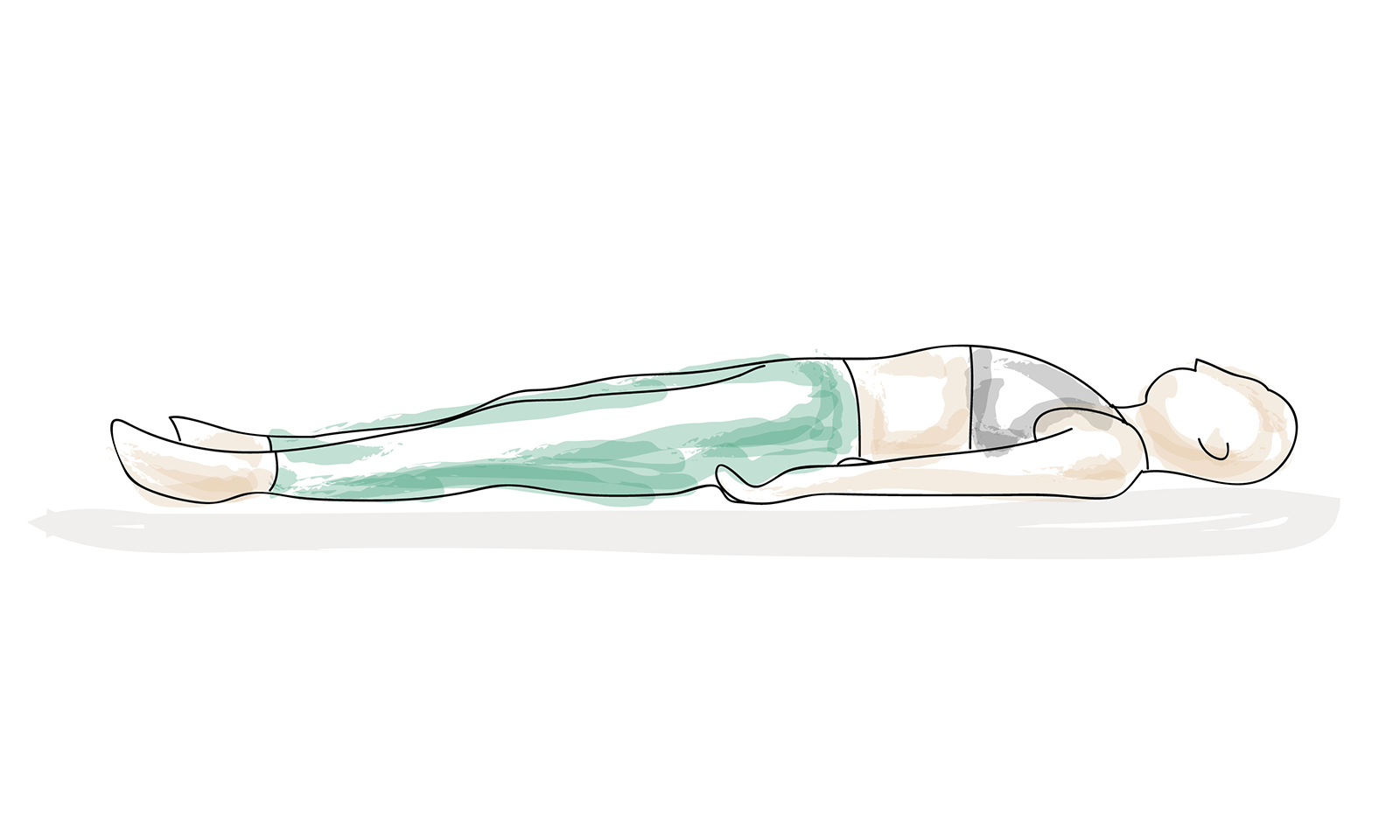

The first place we encounter a very specific inner focus in yoga is in Savasana, the art of relaxation. Here, after extending the muscles and distending the nerves in a more active sequence of postures, we lie still and very consciously begin to draw the mind to particular points of the body to quieten each individual part in order to balance the whole. Savasana, as the name implies, is an asana in its own right and there is indeed an “art” to it. Understanding relaxation requires practice and patience.

From the outside, it appears simple. Lie on your back and relax. Yet for the majority of us, this can be the most challenging of tasks. We become like small children who, when asked to close their eyes and be quiet, scrunch their eyes up, move their limbs about and keep peeping to see if time is up. As teachers, and as beginners at some point ourselves, we know that if you ask a class of adults to lie down and relax, without giving them any particular instruction or preparation, within minutes they too become restless and uneasy, or quickly fall asleep.

For most of us, our main experience of stillness is at night when we go to sleep. The body, being a creature of habit, immediately connects lying down and being quiet with bedtime. If sleep is not the requirement when we are being passive, for some of us a degree of confusion or even anxiety surfaces. The brain becomes very active, the heart beats faster, strange noises in the ears intrude and disturb. We therefore require preparation, guidance, and practice in Savasana, and this then serves as a link to pranayama.

In a normal class situation, students will first go through a sequence of postures to both stimulate and steady the various muscles and nerves and to engage and focus the mind. At the end of the class, there will be time set aside for relaxation. At one level this offers the possibility of dispelling any residual tension, rebalancing any part of our body which may have overworked, and allows a few minutes to quieten the breath. It is also an opportunity for inner neutrality, a time to be conscious of ourselves and the state of our mind and body at that very moment. In teaching Savasana we guide the students through various key areas of their body, first at a more gross level and then the more subtle. Most of us find that we have a degree of mental fluctuation, distraction, and a sort of reverberation in the body. Like a stone thrown into a still body of water, even after the object itself sinks, there are small ripples, little circles around the point where the stone entered the water. Similar echoes appear when we lie still in Savasana. It takes a little while for these to settle.

In yoga, even relaxation becomes a conscious action. We need to see the tensions, the residual ripples, become acquainted with their patterns and habits. And in order to see and feel these disturbances, we must first become still, neutral, aware. It is like lying in bed when it is late and listening to sounds deep in the heart of the night. At first, outer noises and activities distract us, until gradually, as it gets later and silence further descends, we are able to pick up smaller and smaller sounds from further and further away. Footsteps even a block away can be heard. In yoga practice, we try to sharpen our senses to the sound of ourselves and eliminate any extraneous noises, in a way like putting on headphones to pick up only the music we want to hear.

To bring the mind to that sort of quiet awareness, sometimes referred to as a state of innocence, first the body needs to be led into balance. Any contraction or pull of a muscle will draw and hold our energy there so that it is no longer in free circulation. We again need to return to our tangible form, the foundation from where to start. We begin to be mindful in the way we lie down, observing closely if the spine is evenly long, in the centre, the limbs positioned in a balanced way, the head straight and even. Simply tilting the head can bring about unwanted stimulation to one hemisphere or the other of the brain. Moving the eyeballs even behind closed eyelids stimulates thought. All this takes time to experience and it is important.

We can gradually begin to become aware of the position of our body from the inside, by the sensations we receive. By withdrawing our senses from outer stimuli, by allowing the organs of perception to become passive, the eyes, the ears, the tongue, the skin itself quiet and soft, we can on occasion move into real stillness, a point of equilibrium where, though outwardly passive, we are more alert than ever. This is not something we can make ourselves do. It is instead a practice, a turning inwards which may allow us to get a glimpse of being truly quiet. This inner silence and attentiveness is where Savasana aims to take us. With time it becomes a familiar endeavour, sometimes more successful than others. That too becomes familiar. And this is the base from which to start observing and then guiding the breath.

Normal breathing is what yoga master BKS Iyengar calls a zig-zag breath; it has no set rhythm or pattern. It can be difficult to properly watch a normal breath because the very act of observing it tends to condition or change it in some way. So first we need to spend some time just watching the flow of breath, and we will almost certainly notice that it comes in and goes out of a different part of the chest cavity each time, once more to the left lung, then perhaps more to the right upper lung, etc. One side of the chest responds more readily, we find it easier to inhale than exhale or vice versa. There is no even rhythm. We start to perceive ourselves through the breath, what story it tells, what information it gives. It is essential practice, it takes some time. Perception cannot be forced, it grows at its own rate.

To practise savasana then is to be completely passive, yet alert, externally still and quiet, and internally more receptive than at any other time. The brain learns to become more of an observer, a witness, to take a less dominant role. It tends to be new territory for most of us, a different vantage point to look out from. From this perspective we are then ready to specifically prepare the body, that is, the chest, the diaphragm, the lungs, the intercostal muscles, and the ribs for the sustained, slower, longer, and channelled breath that is the foundation of pranayama.

Some of the groundwork will already have been accomplished through the active work done in the postures. There is also another more passive preparation which students will encounter after about 6 months to a year of class attendance. It is at this point that we start to stay longer in the poses and specific sequences made up almost entirely of passive, supported asanas are introduced. These sequences enable us to become familiar with the organs of respiration and with the muscles and body structures involved when the chest is required to open more fully.

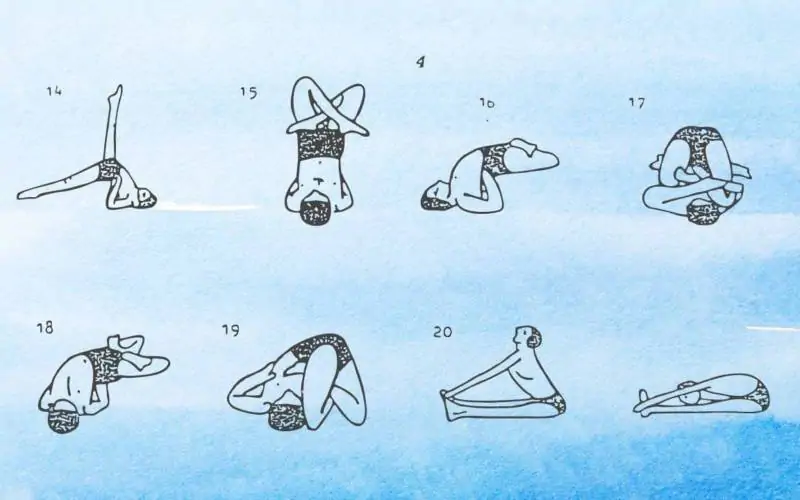

Let us look at three of the supported asanas which can be used in this preparation for pranayama. They are best practised a good few hours away from meals and, for beginners, will be initially easier in the afternoon or early evening.

Each of these postures also conditions our breath in a particular way, perhaps facilitating inhalation or exhalation, or opening a habitually stiff area of the chest allowing the breath to flow more freely there. The “job” here is to observe all of these things, it is to do nothing but be conscious of the more subtle actions which take place inside the torso, and the effect this has on the mind. Become the witness, watch as if looking at yourself from the outside, dispassionately but with attentiveness

Supta Baddha Konasana

In Supta Baddha Konasana we lie back in the bound angle pose over a support and with the help of a belt. This pose has many benefits in practice, including activating and balancing the kidney and bladder regions and spreading the area of the lower abdomen to allow for good blood supply there. It is therefore also particularly useful during menstruation. When practised as a preparation for pranayama, with the support of a bolster placed underneath along the spine, it helps the diaphragm to stretch out sideways, it creates space between the ribs activating the intercostal muscles and it teaches the floating ribs how to open horizontally as required in inhalation. The cavity of the chest is widened and deepened. We begin to get an experience of how the back ribs support the opening of the front of the torso, how to expand the chest and broaden across the sternum plate without effort. For pranayama, physical effort is not only not required, it makes deepening the breath as a yoga practice impossible to achieve. A deep, sustained, and properly channelled breath with minimal physical effort is needed. The supported postures begin to give us an idea of how this might be possible, as well as physically rendering the respiratory organs more responsive.

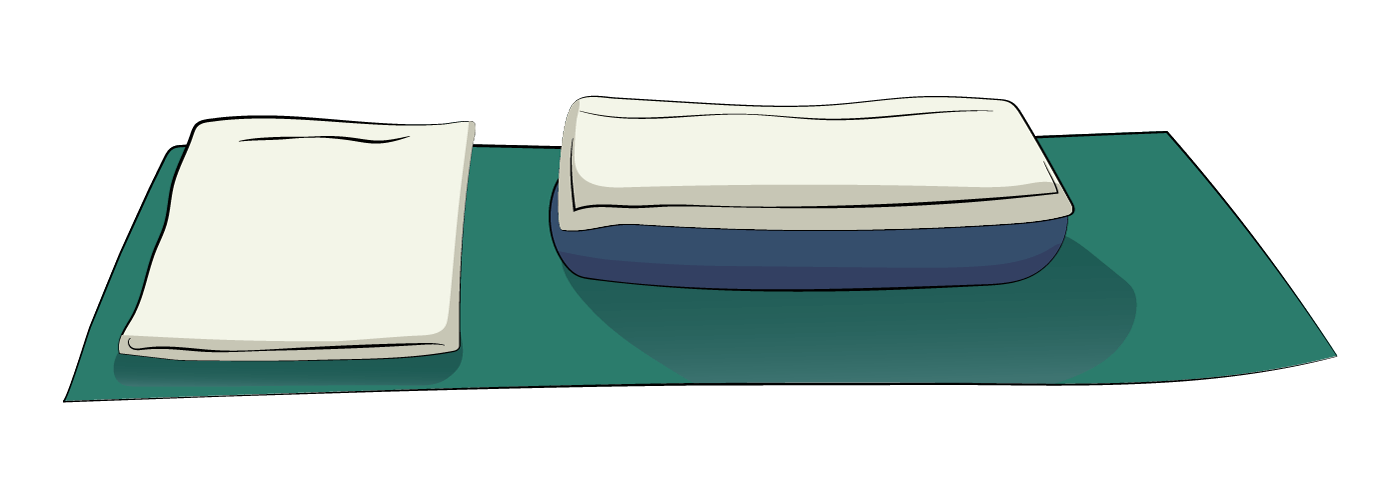

Lie back over the bolster as pictured with the feet together close to the buttocks. Use a blanket to support the head and neck. A belt positioned around the middle of the buttocks and looped over the feet and ankles will help to get the correct opening.

Let your attention go to the physical experience of how the diaphragm is spread, the space between each rib, the broadening of the sternum and of the collarbones, the widening of the lateral spinal muscles.

Is inhalation or exhalation easier for you in this pose? Can you begin to actually perceive the space, the cavity within the chest? Explore from the inside its depth and breadth.

Practise remaining quiet and focussed on the normal breath, the eyes soft as though the pupils were seated at the back of the eye sockets. Let the ears be passive, throat and jaws relaxed. No tension anywhere.

Stay in the pose for about 5 minutes, up to 10 as your confidence and experience grow.

To come out of the pose, sit up and remove your belt and then sit with simple cross legs, bend forward from the hips and rest the forehead on the bolster for a minute or two. Keep the forehead and sternum on the same level. Remain in the same quiet state even as you come up to go to the next pose.

Setu Bandha Sarvangasana- supported

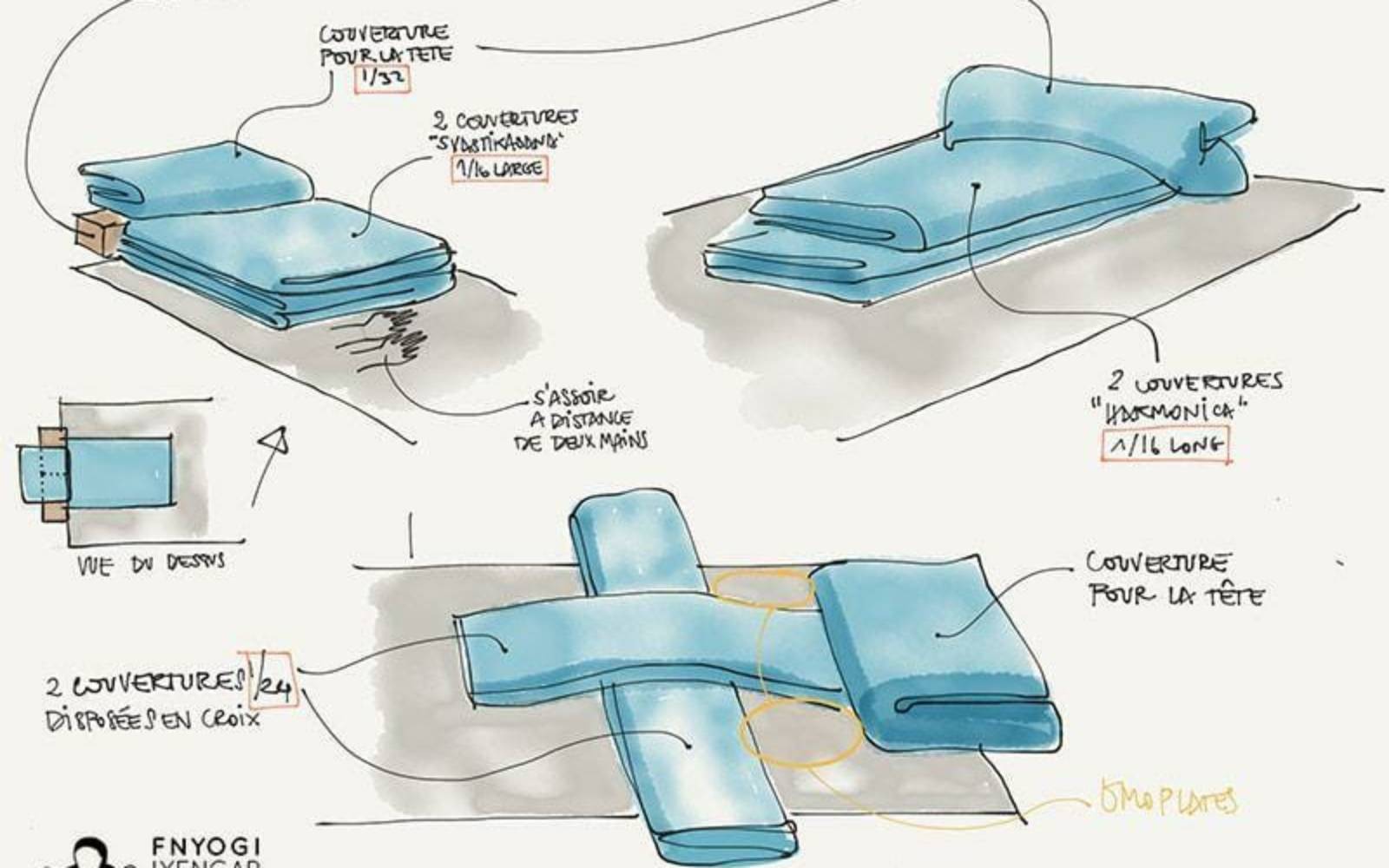

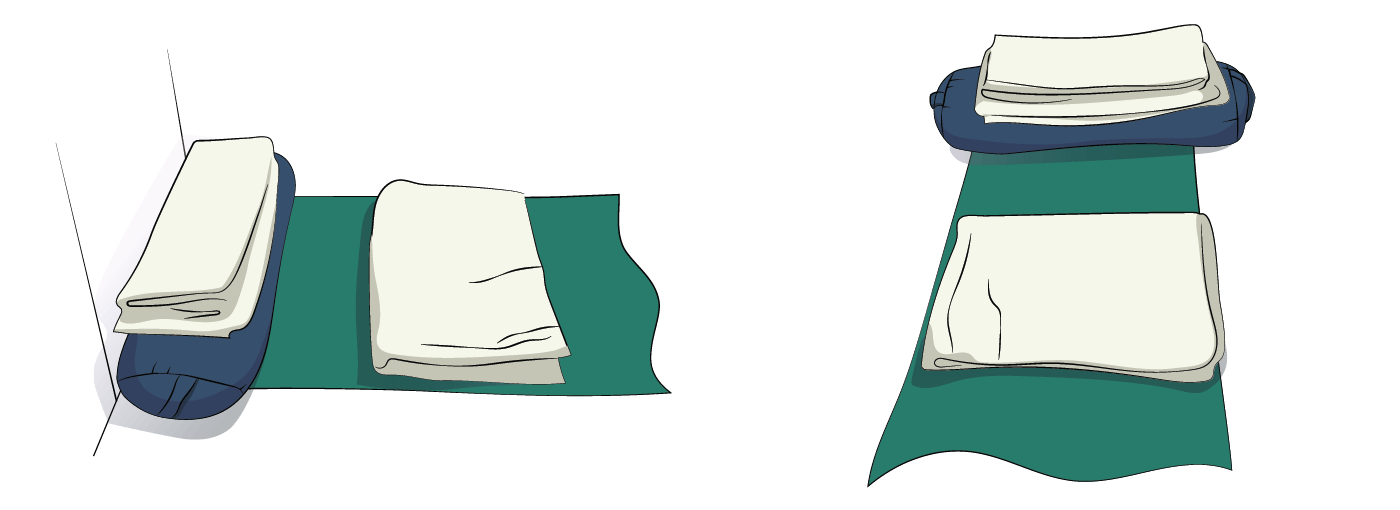

Place two blankets folded in half on the bolster lengthways and have an extra flatter blanket for the head and shoulders.

Sit with your buttocks towards the edge of the bolster closest to the wall. Lie back with your feet to the wall and knees still a little bent with your shoulders touching the floor. Now press the feet to the wall to straighten the legs without letting the shoulders slide further back. Let the skin on the sacrum and buttocks move towards the legs. In the final posture, you will be lying on the bolster with the front edge of the bolster just below the shoulder blades, a little above the lowest back ribs, the shoulders resting completely on the floor and the head as in Savasana, straight, not tilting back. If the chin is lifted and rolling up towards the ceiling, fold the blanket a little higher and place it under your head to bring the face to a passive and horizontal position.

Lie quietly for a few minutes letting your body settle. In all the poses, but particularly noticeable in these supine supported postures, it takes a little time for our mind and body to quieten. Let the face, eyes, throat, tongue, skin all soften and recede inwards to a Savasana state.

Once the outer shape has been taken observe the inner shapes and spaces, become familiar with the “furniture” inside the body, the interior of the physical house you inhabit. How is the chest, the diaphragm, the sternum? See how the back body supports the front body. Let the front become quiet and passive, open to the outside world, ready to receive. And then mentally explore your new surroundings, observe the lungs, the ribs, the intercostal muscles, live in the cavity of the chest. In Pranayama the breath will be brought to circulate specifically in this area. First, get to know it well.

How does the normal breath feel, where is it moving more freely and where less? Is the inhalation or exhalation easier, can you feel even your upper lungs and chest here?

Remain in the pose 5 minutes, 10 for those who are more experienced.

To come out of the pose, bend your knees and slide back to rest with your buttocks on the floor, knees still bent. To relax your back further, turn the bolster sideways and do simple cross leg resting the ankles and knees on the bolster, head, shoulders, and back on the floor. Wait a few moments there and then turn to the side and sit up.

Viparita Karani

Please note that women should avoid this inversion during menstruation and should therefore omit this pose from the sequence during that time.

The last pose in this sequence is called Viparita Karani, one of the most balancing and soothing of all the supported postures. It quietens the diaphragm and abdomen specifically and is therefore very useful in preparing for pranayama. Often a great deal of tension is held in the abdominal area which interferes with and unsettles the flow of the breath. This in turn creates fluctuations in the mind and disturbs our emotions. Steadiness of breath is an essential factor in bringing ourselves into equilibrium.

Place the bolster horizontally, parallel to the wall, about one palm width away. Fold two or three half fold blankets and place them on top. Taller people will need the additional height. Have an extra blanket or towel to put under your head and neck once you are in the pose.

Sit near one edge of the bolster sideways to the wall. Turn to place the head and shoulders on the floor and swing your legs up the wall with your buttocks remaining on the bolster and blankets. Place the extra blanket under your head with enough height to ensure that the face is soft and horizontal, the forehead skin releasing down towards the cheeks. Find the right amount of height, one that also makes the throat feel soft and free of tension and the eyes become passive.

Allow the buttocks to release down and rest on the bolster. Position the buttock bones and back of the legs up against the wall. Keep the shoulders on the floor and see that the head and neck are supported.

Stay in the pose for a minimum of ten minutes. If your hamstrings are tight and your legs are uncomfortable being upright, remain in the pose but bend your knees and place the legs in simple cross legs with your ankles on the bolster, the knees out to the sides.

When the pose is correct the abdomen naturally releases down below the floating rib to form the shape of a small valley. This is important for pranayama, the ability of the abdomen to soften and descend below the lower ribs giving the diaphragm room to spread and open for effectiveness and ease in respiration. Viparita Karani, when well set up, gives you the quietness and steadiness in the breath you are looking for. That is in fact an indication that you are properly positioned. It is well worth the extra amount of adjusting at first to get into the posture in a way which will give maximum effect.

Notice your breath. Feel if it has become softer and if the flow is even. Viparita Karani helps to bring balance between the inhalation and the exhalation. Remain quiet and attentive.

To come out of the pose, bend the knees and slip back off the bolster until you are right back with the head, shoulders, and buttocks on the floor. Place the legs in simple cross legs with the knees and ankles resting on the bolster. Stay there a few minutes and relax as in savasana.

This is the end of a sequence which can be practised to prepare for pranayama. It may take a few sessions for you to become familiar with the poses and how to adjust the supports to your own requirements. The guidance of a teacher is recommended as they can also clarify how to modify the postures in cases of back pain etc.

Nothing in yoga is casual, every guideline or reference is important. Every small area of the body affects something somewhere else and they all influence our mental state. This is where props are particularly useful as we all have different structural requirements, our own individual areas of stiffness and imbalance. The supports we use in the postures outlined above can be adjusted to reach a point of ease with the desired effect achieved no matter what sort of body we have.

The practice of these passive supine postures is an important step in gaining an understanding of ourselves at another level, a quieter level where the problems of distraction and restlessness become more apparent. Here, as in all areas of yoga, we are presented simultaneously with both the difficulty and the means to address it.

Become familiar with the fluctuations occurring in the mind. Become intimate with the breath.

When the breath is steady and smooth it has a simplicity to it, and the mind becomes more still. A sort of peacefulness can be felt. This very stillness, this state of silence, is something to be consciously observed. It can bring us to what has been referred to as innocence, and it is the ideal place to come to in order to start our exploration of the deeper, channelled breath in yoga, Pranayama.

The next and final article will describe a basic approach to an introductory practice of pranayama.

For more detailed information on Savasana, Pranayama and the poses mentioned in this article refer to Light On Yoga and Light On Pranayama by BKS Iyengar, Yoga a Gem for Women by Geeta Iyengar, or Yoga the Iyengar Way by Shyam and Mira Mehta.