Part 1: Sitting in Asana – Prechanting

Sit straight in simple swastikasana. Adjust your seat, the buttocks, properly. Ascend the spine. Keep the head straight. Open the chest. Fold the palms in front of your chest. Keep the bottom of the palms near the bottom of the sternum bone. Close the eyes. Ascend the spine without disturbing the position of the eyes. Eyes passive, receding backwards. Ears passive and receptive. Take the fibers of the senses of perception away from the brain so that the five senses of perception, on the face, are made quiet, and the energy recedes toward the centre of the brain.

Find the centre of the buttock bones. The centre of the buttock bones is near the anal mouth. Don’t sit on the centre flesh of the buttock but on the centre of the buttock bones. Do not come forward from the buttock bones, and do not go backwards. The natural tendency of the body will be to come forward as one wants to seek support. It is a subtle fear complex that makes one come forward, and it is because of a vanity within that one goes backwards. Therefore, be on the centre of the buttock bones and sit straight. Ascend the spine and stretch the outer abdominal walls simultaneously.

When you sit, the centre of the throat, crown of the head, and the perineum should be parallel. The body should be aligned watching these three points. You have to connect these three points in order to find the middle portion, or median line, of the inner body.

Now, allow the eyes to drop in, relax the facial muscles, and the facial skin. Keep the sinus passage passive. Breathe normally and effortlessly.

Fold the palms firmly. This folding the hand in the Atmanjali Mudra keeps your attention firm. You can penetrate deep within. You then feel your existence from within.

Invocation

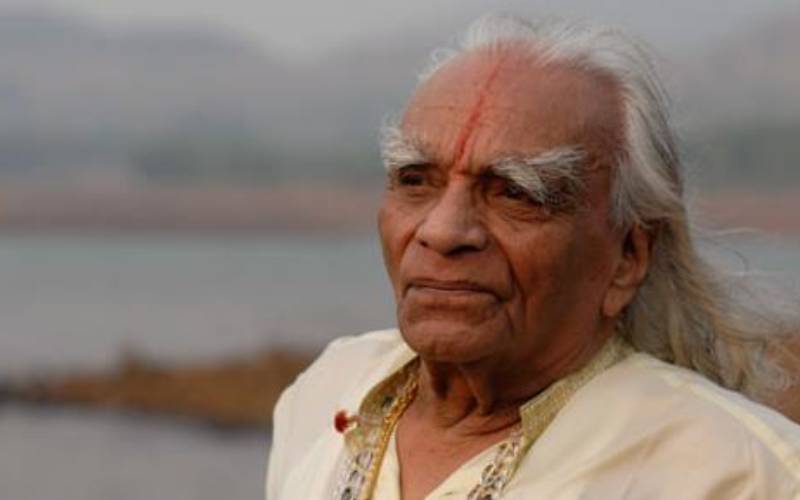

(Guruji recites and the pupils follow.)

Part 2: Sitting Posture for Pranayama

Swastikasana

Sit in Swastikasana, with simple crosslegs. Many of you are not in the habit of sitting on the floor. Therefore, your groins, knees, and ankles are stiff. When you sit, some of you find the knees are higher than the level of the buttocks. The knees do not go down. If you sit on blankets, due to the height, the knees go down because the buttocks are elevated. Therefore, use two or three folded blankets under the buttocks, according to the flexibility and mobility of the knees. Those who have stiff or painful knees should use more blankets. The buttocks should be higher than the knee level.

Evenness in crossing the legs

When you sit, keep the thighs parallel to the ground. If you sit too high, the knees descend, which makes the seat slide. See that the centre of the crosslegs, the crossed shins, and the middle of the navel are in one line. Don’t keep one knee out and one knee in. Both the knees should remain in one line. The abdominal walls will turn out on the side where the knee is out, and turn in on the side where the knee is in.

The Diaphragm: The foundation

Abdomen – the key point

Now, the most important thing to watch in the practice of Pranayama is the abdominal viscera, from the navel to the side corners. When we do normal inhalation, we use the inner abdominal wall, nearer to the navel, not the outer abdominal wall which is away from the navel. While doing pranayama, we have to pacify the inner edges of the abdominal wall, and activate the outer edges.

Diaphragm

The movement of the outer edges of the abdominal wall is initiated by the outer edges of the diaphragm. During normal breathing, the movement is felt only at the centre of the diaphragm. Near the chest is the thoracic diaphragm, and in the throat is the vocal diaphragm. In normal breathing, the vocal diaphragm functions more compared to the other two. The thoracic diaphragm works very little and the pelvic diaphragm does not work at all.

Pelvic diaphragm – a starting point

The secret of pranayama is that you have to first feel the sensation in the pelvic diaphragm. At the beginning of inhalation, the pelvic diaphragm has to create room to support the thoracic diaphragm for it to stretch and extend sideways. The action in pranayama happens only between the pelvic diaphragm and the thoracic diaphragm. The vocal diaphragm does nothing at all. It should be completely passive. The moment you feel tension in the vocal diaphragm, you should know that the breathing is being done on physical force.

Mind and Breath

A passive but watching mind during inhalation

In the beginning, no doubt, you have to use your mind to enter in, to look within. But do not allow the mind to rule the breath. The mind has to just watch the breath. Don’t use the mind or will as the master force. As water spreads on the floor on its own, even if the surface is uneven, similarly, in actual pranayama, you have to learn how to make the breath go in on its own, without mild force. The mind is triggered to watch the breath, which flows in a natural way, like water.

To do Pranayama, you cannot say, “I want to do it!” The moment you say, “I want to inhale for a long time,” the spindles of the intelligence become a little hard and prick the inner body. You become tense and the breathing does not come. So you have to learn to sublimate the mind. Tension and anxiety in the beginning of inhalation is suicide for that particular inhalation.

You have to make your mind passive as you are inhaling and you have to make your mind active as you are exhaling. This pacification of mind before inhalation and activation, alertness, of the mind before exhalation signifies that the mind does not share the same principle during inhalation and exhalation. For example, if my mind says, “I want to inhale,” then, I breathe In fast. If I say, “let me sublimate my mind,” then the stating is slow and controlled. In inhalation, the inner mind spreads like the cotton fibre towards the outer mind and body, while in exhalation, both inner and outer mind is to be aligned, parallel, before you realise the breath.

An active and watchful mind during exhalation

Now what if both the minds are not held parallel in exhalation? The breath comes out fast and the mind sinks. See, when I exhale, I am holding my mind. I am holding the inner fibres of my body. So my mind and inner fibres control my exhalation. While releasing the breath, I feel the firmness of the mind. Similarly, I feel the grip of the mind on the cells and how long it takes for the mind to get itself released on these cells. After doing that, I observe quietly, how the cells contract without volition, on their own, taking their own time. I will not contract them but I observe the changing conditions. They will take their own time to become smaller and smaller and closer and closer. When I don’t force my will on the fibres, they don’t contract but become narrower and recede slowly. That is how you have to observe. I am giving clues so that you can do pranayama with understanding.

In search of the inspirer

The casual body is the inspirer

When you are inhaling, first of all, you have to find out, “am I breathing, or does something strike for me to breathe?” Observe carefully. When I am quiet, before I want to breathe, there is something which explodes inside, and that known as the Self. The core of being. Inhalation begins from the core of the being. When the very idea comes from inside to inhale, there is a slight lift in the dorsal spine near the diaphragm.

As the diaphragm is the organ which has to do the majority of the work, the diaphragm has to be supported by a force which is known as the spiritual force. It is not a physical force but a spiritual force which is known as the core of the being. The very Self helps the diaphragm to lift. That is known as the causal body.

The in-breath and out-breath travel through three bodies and sheaths.

We have three bodies in our system: the causal body, Karana Sarira; the subtle body, Suksma Sarira; and the gross body, Sthula Sarira. These three bodies have five vessels, coats, or sheaths:

- the spiritual sheath, Anandamaya Kosa

- the intellectual sheath, Vijnanamaya Kosa

- the mental sheath, Manomaya Kosa

- the physiological sheath, Pranamaya Kosa

- the physical sheath, Annamaya Kosa

One who dwells in the body is a Sariri, i.e., the self. Sarira means body. The Karana Sarira is the innermost rudiment of the body, i.e., the causal frame, in which the soul dwells. The spiritual sheath of joy forms the causal body.

Suksma Sarira is the subtle body, which is formed of intelligence, ego, and mind. It is encased in the intellectual and psychological sheaths.

Sthula Sarira is the gross body, the material or perishable body which dies a natural death. It is encased in the anatomic and physiological sheaths (see table below).

The breath penetrating through the five sheaths and three bodies

All learners have to know these five sheaths and three bodies, i.e., what a human is made of. When we inhale, we should not use the physical or the physiological bodies. At the beginning of inhalation, we find the casual body, Karana Sarira, or the spiritual body, Anandamaya Kosa. The inhalation has to begin from the core which is the spiritual body.

(Guruji demonstrates.)

I have no inhaled but I have lifted my inner body, the causal body, which initiates the inhalation. The soul is the pillar of the inhalation. So, the support comes when I lift my inner body. Then, that core of the being comes into contact with the consciousness, the intelligence and the mind. From the mind it comes into contact with the physiological body and ends with the physical body. This is the correct inhalation. In inhalation, the breath travels from the spiritual sheath to the physical sheath, i.e., from the causal body to the gross body.

The reverse process of movement is exhalation. You can see that the physical body is held, and then, from the physical body, I release the breath to touch the physiological body. Now, the physiological body has no air, but the mind has. So the mind released more breath. The mind also works. Then it touches the intellect and then it goes to the core of the being. The last particle of breath is released in exhalation, which finally culminates in the Self. When it touches the core of the being, one cannot exhale any further. The exhalation breath travels from the physical sheath to the spiritual sheath, i.e., from the gross body to the causal body.

The Purpose of Breathing

Inhalation – Evolution; Exhalation – Involution

Inhalation is the evolution of the Prakrti from the source, the soul. I don’t want to use the terms “in-breath” and “out-breath.” You all know that. But you all should know the function of the inhalation and the exhalation in Pranayama. You should know how the breath connects the Self to the body and the body to the Self. Inhalation means tapping the core of being. It makes the breath, known as energy, to become Prana. This makes the Self come from the interior layers into contact with the exterior layers. Inhalation begins from the ether, the akasa element, the space within, towards the earth, the prthvi element, the outer body. Whereas, exhalation is from the exterior, outer layers, going inwards. With inhalation the Self evolves. That is why it is called inspiration or inhalation. It is an evolutionary process because the Self is evolving to come in contact with this frame, the body. The seer comes to meet the seen. The dweller comes out to occupy the dwelling place.

Exhalation is the involution that begins from the physical body, which consists of the five elements of earth (prthvi), water (ap), fire (tejas), air (vayu), and ether (akasa). So, you start from earth, that is heavy. Your physiological body is water. The heat or fire in the body is mind. The air is that which pervades, like intelligence. So it is true, you go on descending until you reach the core of the being, the inner ether. Pranayama is a pure meditation. Just sitting is not meditation. Throughout your inhalation and exhalation, you are in contact with the core of the being and its vehicles, the other parts of the body. In exhalation, from the outer Self you reach the inner Self. The entire body is the big/gross self. So from the big/gross Self you go from the interior Self towards the exterior Self, the body. This is the purpose of inhalation and exhalation.

Entrance and Exit

Search the root

Now, the passage of inhalation and of exhalation should be known. When you are suffering from a cold, what do you do?

“You suck and blow!”

True! you blow to clear the nostrils. But do you breathe in while blowing?

“No.”

Then what do you do to breathe in, especially when you have a cold?

“Sniff.”

Right. When your nose is blocked, you sniff. When you do it like that (sniffing), are you opening the nostrils or some other passage?

“Sinuses.”

So the sniffing opens the sinuses, and blowing opens the nostrils. The sinuses are the gates of inhalation and exhalation, and not the nose.

Only when you use the fingers in digital Pranayama, do the nostrils work. When you don’t touch directly with your fingers, the nostrils don’t inhale or exhale. But the nostrils are merely the gates, whereas the sinuses are the real passages. The inhalation and the exhalation are then dependent on the sinus passages.

When you sniff, where does the force come from? The bottom of the top? If there is inflammation in the sinus passages what do you do? Which area of the sinuses draws in the breath? One says, “upper one” and one says, “bottom one.” So you are all thinking, “maybe this area, maybe that area.” But you do not attempt to find out yourself. Does it touch here (bottom), or does is touch there (top)? So is it bottom or top?

“Bottom.”

When you sniff, you do so at the bottom.

As it is in this hall, or any theatre, the entrance and exit are different. Similarly, the passages for inhalation and exhalation are not the same, but different. Take a deep inhalation and feel where the breath touches. Now, a slow exhalation, and see where the breath touches. Does is come in the same passage or on a different passage?

“Different passage.”

These are the things which should be known. The gates for inhaling are under the rim of the sinuses, for exhaling, the top of the rim. Just to say, “sit and take inhalation and exhalation” has no meaning at all. You must absorb these things before you say, “I will start to do Pranayama.”

Nadanusandhana

Listen to the breath and maintain the melody

When you are inhaling, the breath goes under the rim of the sinuses, and you have to listen to the sound. Pranayama is Nadanusandhana. Nada means sound, and Anusandhana means to get engrossed in the sound, of inhalation and exhalation. I do not give you the mantras, such as “Aum” or “Soham.” All of that you can read in books. The sound “sa” of inhalation and the sound “ham” of exhalation, what do they convey? Basically, they convey that the sound of inhalation differs from the sound of exhalation. The sound of inhalation is “Ssss,” and the sound of exhalation is “Hum.” So this mantra is formed from the sounds of inhalation and exhalation, or “Soham,” meaning, “I am THAT,” or “That I AM.” I do not want to emphasize this because it is found in every book. But I certainly want you to have the “Nadanusandhana,” i.e., to get absorbed or engrossed in the sound of the breath. When you start inhalation, the checked, controlled inhaling sound, Nada, comes. Can this sound be maintained from beginning to the end without changing the sound? And can your mind remain absorbed in it? That is Anusandhana. To listen to the sound, keep it controlled, and get completely engrossed in that sound is Nadanusandhana. There is no other vibration except that single vibration. The inhalation sound, as in an instrument, is the melodious sound. So, in the sinus passage, you have to learn to create an E-string, and you have to maintain that melodious sound.

If inhalation is sravana (listening), kumbhaka is manana (reflection), and exhalation is nidhidya (engrossment). All put together this is nadanusandhana.

(Guruji demonstrates in inhalation with a sound which is sometimes rough and harsh, and then controls is so the sound is pleasant, then questions.)

Now, you heard my inhalation sound, don’t I change the sound if it becomes rough? So, see that the sound is rhythmic and melodious from the beginning to the end.

(Again, Guruji performs.)

Suppose it is strong, I control and sublimate my mind at the same time.

(Now, Guruji shows exhalation.)

Even while exhaling, the sound will not vary at all. As the exhalation continues, my ears will penetrate inside to the sound as it gradually fades, it goes to emptiness.

Now, I am going to the emptiness, towards the ether. That is why you cannot hear. I see how long in that soundless state I can remain. Like this, you have to observe the in-breath and the out-breath, controlled by the mind for observing, but not for the mind to be aggressive. Observe passively, and while adjusting, don’t be aggressive. The sound cannot be produced with aggressiveness. The inhalation breath goes underneath the rim of the sinus and produces the sound “Ssss” and the exhalation goes under the rin of the sinus, below the eyeball, producing the sound “Ham.” Then you don’t feel any tension.

The inter-relation between softness of the skin and sound

Do not even keep the fibres of the lungs, the fibres of the chest, taut. You have to learn to release, to relax. Your attention should not jump or attack the breath and its sound. If the rhythm and the melody are disturbed, you have to maintain softness in order to adjust. In a beginner, it so happens that the skin remains taut. A beginning, making the effort to produce the sound, makes the skin of the chest taut. This tautness cannot produce sound. The skin of the chest needs to be soft to get the sound.

(Guruji demonstrates.)

As a beginning, I become tight, so I wait for a second and it becomes relaxed. See, like a beginner, if I pull the skin of the thoracic chest, it becomes tight. I wait quietly, then I relax, and the skin gets relaxed. It is not Viloma Pranayama I am doing. That is different. When you feel that you are taking your inhalation from the starting point, and all of a sudden, you find the starting point has become taut, hard, just give a split second say, one hundredth or one-thousandth of a second is enough, and the tension of the cells disappears and you can continue to breathe.

(Guruji asks the whole class to find the sinus passages.)

Exhale the normal breath slowly and find out where the exhalation comes out. It comes from the bottom of the eyes. Slowly inhale. See, it touches at a different place. These things have to be learnt carefully. Observe, with more and more keenness. Then you will know. Sometimes when you are inhaling you feel a very soothing sensation. That is the real passage, which you have to catch. It doesn’t come in one day. Sometimes it comes, sometimes it doesn’t come. Sometimes you have to struggle to trace the passage. Sometimes it comes on its own. Then you know that it is the correct passage to operate. Now all of you do.

(Class does Ujjayi Pranayama.)

Asanas Contribute a Great Deal to Pranayama

Asana – Pranayama – Dhyana

The very important thing that you have to take care of while doing inhalation are the eyes, eyeballs, and pupils. They have to be kept down in Pranayama. The only difference between meditation and Pranayama is that in Pranayama the head is kept down, and in meditation the head is kept straight. If you do not take the head down in Pranayama, the respiratory muscles of the neck or the vocal diaphragm are passive. That is why Salamba Sirsasana and Salamba Sarvangasana are essential. When you do Sirsasana, the diaphragm spreads to the sides. When you do Sarvangasana, the neck muscles become soft. So you educate the spreading movement of the thoracic and pelvic diaphragms in Sirsasana, and you educate the passivity of the vocal diaphragm in Sarvangasana. In the inverted poses, you realise that the vocal diaphragm is not at all necessary in deep breathing. However, control over the thoracic diaphragm and the pelvic diaphragm is essential in Pranayama. When you do Setubandha Sarvangasana, you observe that it is not the thoracic diaphragm that functions, it is the pelvic diaphragm that works, because it pulls from the pelvic rim when you are inhaling and exhaling. Give your thought to each asana and observe. In that way, you realise where the source point is for correct inhalation and exhalation. Then you improve a great deal.

I will give you a few more examples. Some teachers will ask that you do deep breathing in Trikonasana. Many people say that Iyengar doesn’t teach breathing in asana, whereas others are teaching deep breathing in asana. While doing Trikonasana, if you do deep breathing, your head will move backwards and forwards, so you will be unstable, fluctuating, shaking your body, whereas you should be stable. Even if I ask you to do, nobody knows, or will see, the fluctuations. Your attention goes on the breath and not on the unstable body. In Trikonasana, the lungs breathe in a different part than in Parsvakonasana. In Virabhadrasana, a different part. In Paschimottanasana, the lungs, which take the in-breath and out-breath, are not the same as it was in Trikonasana. I have studied all the asanas and have observed how, in the asanas, the breathing takes place. In Tadasana, breathing is different. When I say that the breathing is different, it means that the muscles being used for inhalation and exhalation in each asana you are performing, are not the same, they are different. How can I teach deep breathing, which is a gross movement, when I know something more subtle?

In Trikonasana, you only use so much (side bottom corner of the chest). In Parsvakonasana only so much (top corner of the side chest). In Virabhadrasana 2, you use on which side you bend your knee, the other side doesn’t work at all.

Is it not interesting to know all these things? But you have not studied. I have studied and that is why I am meditative while doing the asana. But to outsiders, “NO!” For them, I am a physical yogi, but inside I know what I am doing.

Let me come back to the tension in the eyes and the vocal diaphragm. You have to learn that the vocal diaphragm should always be passive. When we are inhaling, we know to keep the head down, but we are not aware that the pupils of the eyes go up. Normally, what do we do? I show you, my head is up but the pupils of the eyes are facing down. Within a few seconds, we do not know that while we are inhaling the pupils of the eyes are getting hard and tense. We think that we are inhaling, but actually, the eyeballs are inhaling. So we have to learn to keep the eyeballs passive. How do you know if the eyes have become tense? When you are inhaling, keep the index finger of both hands on the bridge of the nose with the head down.

(The class is doing.)

Take off the specs, the rim of the specs will not give you a clue. Don’t inhale, keep the head down and feel where the index finger is resting on the bridge of your nose. Slowly take a deep inhalation. What happens to the bridge? What happens to the index fingers? They go up! The moment they go up, you know something has gone wrong. As you are inhaling, pull the bridge of the nose down. Use a little force on the index fingers to pull the bridge down while you are inhaling. The bone of the fingers touches the bone of the nose. Observe only the inhalation. The mistake comes in inhalation, not in exhalation. In inhalation, you have to pull down. Don’t pull down in exhalation, it goes down on its own, that is the beauty of it. What do you feel in the brain now, when you pull the nose down?

“Quiet.”

You understand? That is mediation. If you do not feel that same sensation, then you have done incorrect Pranayama. You may show that you have expanded your lungs, or held the breath for too long. But all that will only be quantitative Pranayama and not qualitative Pranayama.

Now, how do you know if your ears are blocked? Insert the index fingers into the ear holes. In normal breathing, measure the dilation of the ear holes. Now, while inhaling, if the ear holes become smaller, there is tension. Make the throat passive, and taking the head down, you get dilation. In exhalation, the ear hole will go further in.

Part 3 Retention of Breath (Kumbhaka)

Physical – Mental – Spiritual

Now, what makes you hold the breath? I am teaching the holding of the breath. Take a deep inhalation, hold the breath, and observe again. What made you hold the breath? Observe!

“Diaphragm.”

What made the diaphragm hold?

“Throat.”

Throat? I already said not to use the throat at all.

“Ribs.”

What made the ribs hold? I am giving a clear picture so you will not make mistakes after I leave tomorrow. Find out. Observe!

“Consciousness.”

What makes the consciousness to hold on? When you finish your inhalation and you are going to do retention, what happens? At the end of inhalation and the beginning of retention, what is the state? Is there a mind or is there no mind? Tell me.

“No mind.”

Then how can you say “Consciousness?” When there is no mind, how can it be consciousness? I approved it because at least somebody said something close to the answer. So the Self charges the consciousness and the diaphragm, which is the root for the lungs to hold on. The breath does not hold on its own. The breath, that is the air, is never stable. Something has to make it stable. The Self, Atman, charges the consciousness to stop the movement of the intaken breath.

Now hold the breath. What happens to your brain, your eyes, your ears? It is taxing your nerves, is it not?

“It is heavy.”

That is egoistic retention. Now hold the breath and study the beginning of retention. There is a void, the void is a negative state which is called Manolaya. But the void gradually disappears and the Self comes up, “IT” is holding, this is called Atmasakti. In two or three seconds, the Self recedes and the mind dominates. At this stage, the “I” is holding, and you are caught up again. Then the mind holds the breath. You have to observe which one created the void, the Self or the mind. Can you bring the Self to the surface so that there is no void? That is Kumbhaka. In other words, after the inhalation and before the retention begins, there is a void. From that void, the Atman comes to the surface. Unfortunately, the mind overrules and the Atman goes back, and the spiritual Kumbhaka gets converted into mental Kumbhaka, and finally becomes physical Kumbhaka. I don’t want this regression. See whether you can retain the spiritual Kumbhaka.

Qualitative analysis

Now try. The Self lifts the body when you are about to do the Kumbhaka. You have to maintain that lift of the Self and wait for some time, but not too long. Now do you know what happened or not? You don’t know at all. Do it again. Take a deep inhalation, involving the Self. Let the Self come up to the surface to hold. After some time, find out whether the one which helped you to do the Kumbhaka sank or not. Is the body skin also dropping at that moment or not? The Self goes inward away from the skin and the skin on the chest drops. Still, you are holding the breath. You are continuing to do Kumbhaka, which is not the right Kumbhaka at all. The pure Kumbhaka is what you bring up in the inhalation and at the beginning of retention, it charges the body and mind and it changes the body and mind. “How long chronologically can I retain that lift which came in the beginning? How long can I keep it?” You have to examine. The moment you feel it is slipping, that means your time of Kumbhaka is over. IT means that the Self disconnected itself from the body. It says, “Oh! You (the body) become proud. I don’t want to be with you.” The Self withdraws. The Antar-Kumbhaka, inhalation-retention, no longer remained as Atmic-Kumbhaka. It became Asmita-Kumbhaka, egoistic retention. If you hold the breath and continue, just to show how long you can hold the breath, then I say, “You are a fool!” It means you are playing with your organs. Your pride is saying, “I can hold the breath for one minute.” Such types of Kumbhaka will not let in the light of knowledge but will lead you toward darkness. Can you hold the breath in the first instance with that purity? At the end of inhalation and the beginning of retention, there is no separate mind. The mind is not separate from retention. That mind is not negative. On the contrary, it is full. Because it is not compartmentalized. It is complete. It becomes a single mind, and that single mind spreads from the core to the extremities. Can you retain that evolution of the single mind?

Why do we do Kumbhaka? Not to hold the breath, but to bring the hidden Self to the surface, to be with the Self for a while. So when you hold the breath, you have lifted the soul. You have made the mind become a single mind. Can you maintain that single state of mind without any oscillations or collapse? That state is a divine state in retention.

The moment you play, the purity vanishes. You, your body, your breath, your retention, the Self, everything, separates. The unity vanishes and the diversity comes.

Observe. I am doing Kumbhaka, and my body is sinking. That is not Kumbhaka at all. It is a force which is not a pure Kumbhaka, there is no divinity. Now, I am holding. My skin does not drop at all. And when I drop, see where my clothes become loose. It shows that I am not doing the Kumbhaka. This Kumbhaka is Rajasic Kumbhaka. Rajasic Kumbhaka is merely an external appearance in which the body and the mind are exposed. But in Sattvic Kumbhaka, the Self is disclosed. Sattvic Kumbhaka shines from within, comes from within, expresses from within. That is illumination which you should know in Kumbhaka.

The foundation for Sattvic Kumbhaka is in the structural body

How to get this Sattvic Kumbhaka? In order to get it, you have to understand the process of inhalation and exhalation which I explained before. In inhalation, the armpit chest is the brain as it is in Sirsasana. See, this centre is the sternum, and these are the lungs. When I sit, is my centre body higher or are my side lungs higher? Centre or sides?

“Centre.”

The centre is taller, so what did I do? I lifted the lungs to be on par with my sternum. When we do a normal inhalation, what we do is move the area around the nipples. Look at my ribs. We move the centre region of the chest, this movement is wrong. Now see the side ribs. There is a difference between the centre and the sides. The side ribs remain lower than the centre chest. This movement of the body during inhalation is wrong. Every now and then you have to adjust your body as you are inhaling. There should not be any difference between the centre and the sides. They should be on par with each other. When inhalation is done from the centre, it becomes physical inhalation, since the crown of the diaphragm becomes hard. In the inhalation, you have to learn to keep the crown of the diaphragm passive. You have to learn to work from the wings of the diaphragm.

Here is the centre of the diaphragm, the dome of the diaphragm. The floating ribs are at the bottom corner of the sides of the chest. The purpose of the floating ribs is unknown to medical science. Only those people who do Pranayama know the purpose and use of the floating ribs. If the floating ribs are not there, you cannot turn to the side at all. Can you turn these ribs? How can you turn without using the floating ribs? The true ribs are the fixed ribs. The fixed ribs cannot move at all. So these fixed ribs are made to move by the false ribs. The floating ribs are the real brain of the entire torso. If there are no floating ribs, breathing, also, is impossible. Not only the diaphragm but also the floating ribs are involved in breathing. The diaphragm is connected to the head of the floating ribs. When you are sitting straight, the moment you inhale, you can see the extension of the rim of the diaphragm going towards the head of the floating ribs.

(The instructions to the whole class.)

Now, all of you try and find out. Sit straight and inhale. Feel the movement of the diaphragm. The corners extend and touch the head of the floating ribs. Drop the diaphragm and it is dead. You cannot do the breathing. That is why you have to sit straight and create space between the pelvic rim and the floating ribs. The space makes you aware of the diaphragm and the floating ribs before you take a breath. You have to observe, whether your diaphragm is connected to the floating ribs or not. When it is connected to the floating ribs, the two heads of the floating ribs opens to the extreme side corners in inhalation. As they open, the diaphragm stretches horizontally towards the end. Hence, the initiation of the inhalation is where the diaphragm comes in contact with the floating ribs

See the diaphragm at the center as well as at the outer sides. When you inhale, only the outer sides should come up. The centre, the dome, should dip.

Analyse the difference

(Guruji demonstrates.)

Now see the faulty action. When I inhale using the center of the diaphragm, the upper front chest comes forward and the sides move back. The outer sides of the chest are dead. My chest is like a slanting board. Now, see the correct action. When I use the sides of the diaphragm, connected to the floating ribs, the sides project forward. So I am creating space on the interior intercostal muscles for the diaphragm to expand so that the air goes in and pumps towards the lungs. You can watch the correct movement of my skin at the back of the chest. When you sprinkle water on a hot oven, it is absorbed. So, too, when I inhale, my back gets absorbed and the cloth stretches and moves towards my frontal body. I do not push the lumbar in.

When you are inhaling, the breath goes down the windpipe and reaches the bottom. As you move the floating ribs to the sides and upwards, you create space. The moment the space is created, the in-breath goes to the sides through the bronchial tubes towards the air sacs and supplies the first fresh breath energy. As you go on inhaling, the breath moves up. The first breath energy circularly moved up with the continued inhalation. After full inhalation, the used breath is collected at the base of the throat. The unused breath is still in the abdominal area. So when you are exhaling, the in-breath that was taken at the end starts moving from the abdominal area to the sides, feeds the lungs, then allows the used breath at the base of the throat to move out. Each time, the lungs take full advantage of that breath, which has been drawn in, before the breath is released. But if you do deep physical breathing, the air isn’t even pumped into the lungs, it waits to come out, and therefore, you are already out of breath.

There is a difference between yogic Pranayama and deep breathing. In yogic Pranayama, you direct your breath with your will to go in a particular direction in order to spread, whereas in deep breathing it goes directionless, harming the longs. Deep breathing is not yogic Pranayama. Yogic Pranayama means observation when you are inhaling. For example, I don’t know the city of Sydney. Someone has to guide me. You can say this torso is a city that I do not know. So, it is my consciousness that has to act as a guide within me. Similarly, when you are inhaling, the consciousness should help the breath. When you inhale, the consciousness should say, “Come with me. Come with me.” It has to lead. Now, all of you try.

(The class is doing.)

Take a slow, deep in-breath. As you begin, feel the consciousness at the diaphragm band. The consciousness has to move outwards and upward. It should say, “I will show the city of my lungs.” Then you get that action.

When you exhale, how does the breath come out? With freedom, isn’t it? Exhalation, also, should be done with the same length of time, as it took a long time to reach that place. You are relaxed when you returned the breath. Your brain has to be relaxed and the breath has to come out with the same controlled speed which it took to go in to reach that place. The skin on the chest should not get closed.

(Guruji makes the class do Kumbhaka.)

Part 4. Pranayama in Savasana

Use of the blanket

(Guruji demonstrates on a student lying on three blankets.)

The inhalation breath was pushed to the sides of the lungs. That is why you have to use the blankets. The blanket is supporting the spine. The spine does not sink, and the heavy ribs at the back are easily lifted.

Now remove the blankets and lie flat on the floor. Take a deep inhalation. See, the spine is convex. It becomes heavy and pulls the ribs down. So one cannot move the breath at all on the sides of the chest. Due to the gravitational load, and pull, the spine becomes a gross body, a heavy body, for breathing. In Pranayama, the outer body does absolutely nothing without proper support of the spine. In Pranayama, only the spine is the brain, the head is not the brain. The spine, i.e., the brain, is not giving any signal to take a correct inhalation because the spine is dull, not alert. It is sinking. It has become heavy and gross. If the spine is supported, it goes in and the spine behaves like a subtle body.

Use the blankets so that first the lumbar spine is slightly concave and the chest opens. Now the spine is alert for him, the student, to take the breath. The spine dictates to him, “Don’t disturb me, move me gradually.”

Now, use the blankets in a slightly different way.

(Demonstration showing the placement of the blankets.)

Take three blankets folded in half, and place them in a stepped manner. Keeping the sacroiliac on the floor, the lower lumbar on the first step, i.e., the first blanket; then the middle lumbar on the second step, i.e., the second blanket; the top thoracic on the third blanket and the head above on the top, on a higher blanket. This way, the spine moves step by step while you are inhaling. If you keep all the blankets directly on top of one another, the height is more for the whole spine, and the spine remains with tension. As you carefully place a baby on a bed, similarly, with care, you have to place your own spine.

Head, ruling the body from above, like a king

Can you see the smoothness of the movement because the spine is concave? To move the spine in towards the anterior body, learners need to use blankets in the beginning. The head should be above the level of the chest. If the head is down and dropped backwards in Savasana, the tension will be on the vocal diaphragm. I have already shown you about the bridge of the nose. It gets pulled towards the head, i.e., to the north (head is the north and the feet are the south) and while inhaling, the brain sucks the air. With blankets correctly placed under the head, the brain is induced to observe. The head is the observer, the lower chest and the abdominal area are observed. The head is the object, and the chest becomes the subject. The brain has to watch the flow of the breath. The observer has to be higher than the observed. If you take away the blanket, then you cannot observe the flow because the brain is tensed and it becomes the doer. The lungs to not become the doer. With a blanket under the head, the head becomes the audience, the chest/abdominal area become the actors. Even the eyeballs will have no tension. They remain passive.

Silence the thighs – silence the ego.

(Instructions to the whole class.)

Everyone lying out, facing the same way. Tall people may need a brick or extra blankets under the head so that the vocal diaphragm is kept passive. If there are no extra blankets, then keep the head on a vertical brick. It pricks a bit, but you learn. Place the prick a little to the inside so the back of the neck also touches.

Why are you lifting the thigh muscles? You people are slow to catch. You are only doing with your egoistic intelligence. I am using the word “intelligence,” not “intellect,” there is a difference between intelligence and intellect. Intelligence is subjective. Intellect is developed through your use of the brain. Now, see my Savasana.

Demonstration by Guruji

I move the edge of the sacroiliac muscles down towards the feet. When you lift the thighs, the sacroiliac muscles automatically move back. I move them down with my fingers. When you stretch your legs, the sacroiliac muscles move up. So use your fingers to move the outer sacroiliac muscles down. Lie down and adjust the sacroiliac area. Do not do breathing immediately. If you begin to breathe suddenly, the thighs will get puffed. Pacify the thighs.

Self-adjustment

Find out if passivity has been set in the fibres of your chest. Pacify the abdominal organs. In case you feel the pinching on the skin at the back of the shoulder blades, adjust with your opposite hand. You can move the skin of your shoulder blades. For the right shoulder blade, use the left hand, and vice versa. One by one move it away so the shoulder blades give room to expand more. Keep the eyes and ears passive. Close your eyes. After closing the eyes, dip the eyeballs into the eye-sockets. Watch your tongue. Do not keep the tip of the tongue tense. If the tip of the tongue touches the upper teeth or the upper palate, then the sinus passages get blocked. Let loose the tongue, as in sleep. In sleep, there is no movement of the tongue. You have to learn in Savasana, Pranayama, and meditation to keep the tongue as passive or negative as it is in sleep.

The back of the head should not be to one side. Measure the centre, and be on the centre of the back of the head. The middle of the nose, and the middle of the forehead, should be exactly facing the sternum. Be passive.

Normal breathing differs in Savasana

Now, watch your normal breath. You’ll be surprised to know that the first inhalation and exhalation or the second, or third, or fourth, do not touch the same parts of your chest. They touch different areas but in a sequential order. Each time, the movement differs. The inhalation breath is drawn to certain parts of the chest and the exhalation breath to other parts. The second breath, also, will be touching a different part, and not the same part. Observe, sometimes your inhalation is for only two seconds, but your exhalation is a little longer. Sometimes your inhalation is longer. You spread your ribs and then exhale. These various functions in normal breathing will give you a lot of knowledge to understand the function of the lungs. When you do normal inhalation and exhalation, not Pranayamic breathing, the normal breathing hits the skull. However, the same normal breathing, in Savasana differs. Here is does not hit the skull, or brain, but spreads in the entire chest and abdominal area. Each breath we do is done by the entire body. The inhalation is done by the entire body, the exhalation is also done by the entire body.

Sustained Breath

Now watch. Let your intelligence, like a gatekeeper, observe the movement of the in-breath and the out-breath. Without your intelligence observing, your breath should not go in, nor release from the lungs. Do not do deep breathing. Instead of that, watching whether the normal breath can be transformed with your attention. Then you will understand the functioning of the intercostal muscles of the chest, between the ribs. When the intercostal muscles are observed, the movement differs, the grip differs, so the understanding differs. You will be surprised that your normal breath becomes a little longer. That is known as “sustained in-breath” and “sustained out-breath”. The intelligence plays a major role with the in-breath and out-breath.

(Guruji notices a student lying incorrectly, so instructs his assistant to adjust, stating, “The bridge of his nose is above. Adjust the back of the skull so that the bridge of the nose goes down. Extend from the neck to lengthen.”)

The spread of the diaphragm

Observe the movement of the diaphragm, the rim of the diaphragm, tip rim and bottom rim. In conditioned inhalation and exhalation, the diaphragm moves with discipline. Now, just wait, remain quiet. Can you horizontally spread the floating ribs toward the sides without inhaling or exhaling? Extend the floating ribs and observe how the dip takes place on the frontal chest when you spread the diaphragm and the floating ribs to the sides. Observe the dip on the inner portion of the breast or nipple. For men it doesn’t go up, it dips down. That is the clue that you have to dip down the inner portion of the muscles near the windpipe and allow the outer portion to expand.

Allow the breath to come out of the lungs gradually. Don’t use force. Then, start the inhalation by spreading the floating ribs to the sides and dipping the inner edge of the breast and try to move the breath to go to the outer edge of the breast bone.

The art of using the lungs

As you look at the beauty of the external world, look now within your lungs. How the breath is moving on the right lung and the left lung. You have to use your intelligence and discrimination to see that the breath moves on both the lungs evenly. If one side of the intercostal muscles becomes active, nullify that. Negate it, and positively create on the other side, and the breath will be pushed to that side. While exhaling, move the side ribs towards your armpit, and slowly exhale, keeping the head of the diaphragm up. Ascend the head of the diaphragm and allow the breath gradually to come. The lungs should be dried gradually in exhalation, not dried at once.

The art of using the rim of the diaphragm

After exhalation, the rim of the diaphragm at the top should be in line with the rim of the diaphragm at the bottom. If the rim of the diaphragm at the top is up, then your exhalation is incomplete.

The end or completion of the exhalation is known only by the rim of the diaphragm. The top rim should be running parallel to the bottom rim at the end of exhalation. While keeping the top rim down, slowly inhale and move the bottom rim, so that it is parallel with the top rim. The moment that the top rim jerks, your inhalation is short. That means, though you feel the lungs are full, they are empty. Pacify the top rim and activate the bottom rim of the entire diaphragm from the right floating ribs to the left floating ribs.

At the end of exhalation, see that the top rim does not jump up but moves towards your spine. Exhale, maintaining the width of the diaphragmic rim. When the exhalation comes to an end, you should feel passivity in the abdominal viscera. Exhale until you find relaxation in the outer edge of the abdominal viscera.

When inhaling, watch the outer edge of the abdominal viscera, which is one road. Inhale by sucking the outer edge and at the end of inhalation, the head of the abdominal viscera should be in contact with the inner and outer rim of the diaphragm as well as the right and left. The inner and outer head of the abdominal viscera should be parallel.

It is easy to move the inner head of the abdominal viscera but very difficult to adjust the outer one. So all Pranayama practitioners have to give thought to the outer head of the abdominal viscera, which is nearer the floating ribs. At the end of exhalation, the adjustment is on the abdominal viscera. The outer edge of the abdominal viscera is normally shorter than the inner wall. In Pranayama, you have to learn to extend the outer wall of the abdominal wall toward its head, toward the diaphragm. In the exhalation process, you have to observe that the head and tail of the abdominal viscera run parallel to the ceiling.

Do not inhale until you find the level of the abdominal viscera, outer wall, inner wall, as well as the right and left sides. They should all come to a state of complete passivity. The cells of the abdomen should feel the emptiness. Then the exhalation is complete.

The chest should not collapse in exhalation

You should not move. This hits the brain. Those who feel the load on the brain, watch the two collarbones, the side ribs, and the side chest. Watch that they expand in inhalation. This width should not collapse in exhalation. Do not press the periphery of the chest on the sides. Watch the inhalation, how far the side chest broadens and opens out, and in exhalation how it becomes passive without sinking. So if the sides of the chest do not sink but become passive, your second breath becomes more minute, or subtle.

Trace the end of exhalation

Keep your ear on the sound of the in-breath and the out-breath. The sound should evaporate at the passage of the sinus. Do not try to silence the sound, the sound should naturally fade to such an extent that even your ears cannot catch that echo-sound of the inhalation or exhalation. The breath will be sticking to the mind, sticking to the cells, so you have to empty that, also, before you inhale. Relaxation is not just in the physical fibres. Relaxation reaches to the cells, goes to the mind, to the intellect, to the consciousness. Until the consciousness feels that void, the emptiness in the exhalation, one should not inhale.

When you start inhalation, remember that you have to open the floating ribs to the sides. When you are taking the floating ribs to the sides, move the bottom middle ribs, the top middle ribs, and then the top ribs. The collarbones should extend towards the armpits. The top collarbones and the top chest should be firm in the process of exhaling. Those who drop the top chest become a little nervous. It shakes the mind. In order to see that the mind does not shake, the top ribs should be connected to the armpit in the art of exhalation. This freedom of the top ribs brings stability of mind.

Keep the manas cakra open

To maintain the stability, both the eyes should be looking into the core of the being, which is seated below the diaphragm. The diaphragm floats on the core of the being. We call it manas cakra, or the wheel of the mind. In order to observe this manas cakra, you have to widen sideways for the breath to go in. That is the source of the mind. The breath makes its passage and paves its path to reach the source of the mind.

Face the silence with silence

Now, all of you remain quiet and observe normal breathing, which is now more intimate to you than the one you did in the beginning. Now, you can understand the intimacy of the breath. The body does not want to exhale at all, it holds, and allows the breath to go gradually. See the silence of the mind, silence of the ears, silence of the eyes, silence of the facial skin. If you create tension, then you come to the external world. Do not jerk the body, do not break the silence of the mind, and do not expose the senses of perception to the external world.

Part 5. Coming out of Savasana

Be within throughout

Turn to the right side. Without disturbing the head, roll the head to go to the right side. Wait for a while. Feel the coolness of the brain. Watch how the brain does not want to function now. It wants to remain quiet, as though ice is being kept on the head. Without opening the eyes, roll to the other side, so that the other hemisphere of the brain also gets the taste of the coolness. The moment you open the eyes, the brain becomes hot. You already want to see the world. Do not get up straight, get up from the side.

Spiritual essence

All of your sit. Feel the state of your brain now. Is it silent or not? I didn’t teach you meditation, but you are now in a state of meditation. There is no mind, no brain. Don’t you feel it? That is the spiritual essence of yoga, it comes on its own. It is the property of Yoga. Enough for today. God bless you all.

Don’t be greedy

I’ve tried my best to give you, in this limited time, what I could. If you can stick to this practice, then the Universal Spirit, who is the protector of all, will definitely protect the practitioner, as long as you don’t jump ahead, saying, “let me do more.” The moment you start using your brain with greed as the motive, you are lost. So use the mind, consciousness, carefully. The protector will come to protect you. Practise well. God bless you.

If I have said strong words, forget about them. But where I have said good words, take them. I have used some strong words to awaken your dull minds. As soon as that dull mind is awakened, my strong words disappear. So don’t ponder on those words. They are momentary. Take all the good points. Take off all the bad points of my shouts in anger, and whatever else, and put them in the wastepaper basket. Take the other side, the good points. Then God will bless you all.