“Success will follow him who practises, not him who who practises not. Success in yoga is not obtained by wearing the dress of the yogi or sanyasi, nor by talking about it. Constant pracatice alone is the secret of success. Verily, there is no doubt of this”.

— Hatha Yoga Pradipika Chapter I, verses 64-66

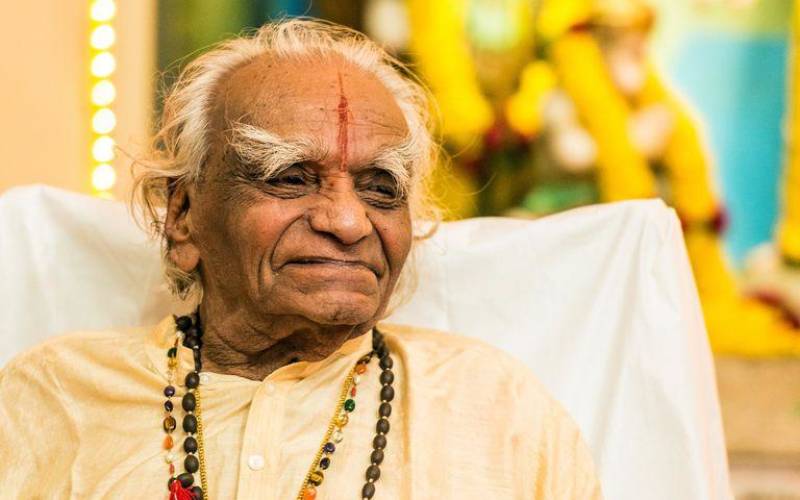

BKS Iyengar never called it ‘Iyengar yoga’

35 years ago the term ‘Iyengar yoga’ was barely used. BKS Iyengar had only just opened his new yoga institute in the India city of Pune, and it was difficult to find a bookshop which carried his ‘Light on Yoga‘, now recognized as the standard reference for yoga asana practitioners. Indeed, Mr. Iyengar did not coin, or use, use the term ‘Iyengar yoga’.

As yoga became increasingly popular in western countries, it was his pupils who felt the need to differentiate what they were learning and practising from other forms of yoga. At that time, Iyengar yoga had the undeserved reputation of being fierce, perhaps even aggressive, certainly more physical than spiritual, and not for the faint-hearted. But perceptions have changed and Iyengar Yoga is now just as likely to be referred to as ‘furniture yoga’, precise in alignment and good for beginners; the implications being that the real yoga challenges may lie elsewhere and that Iyengar yoga is not physical enough, not sufficiently tough anymore.

Changing perceptions to one side, what is the essence of Iyengar yoga and why are people practise drawn to it? Is it Hatha Yoga or something else? Is it one thing in Australia, something else in the United States? In reflecting on my own yoga journey, I don’t pretend to speak for other Iyengar teachers and practitioners. Some of my thoughts may well be shared by them, but only Mr. Iyengar would be able to offer the definitive response.

Discovering Iyengar yoga

When I first started Iyengar yoga in 1976, these questions were not in mind. I ran into yoga, almost accidentally, through a friend living in Florence, Italy who offered the chance to study with Dona Holleman, one of the earliest western teachers of Iyengar yoga. My first yoga experience was a two-week summer intensive yoga retreat with people who were much more experienced and teaching. I jumped or was perhaps thrown in at the deep end!

I had been working as a conference interpreter for three years, and in High School had done a lot of swimming training. I was not unfamiliar with either physical discipline or mental focus and had found both swimming and interpreting to be satisfying, though tiring, challenges. I would do one to balance the other. It had never occurred to me that there could be an activity which combined physical discipline with mental focus, and yoga both stimulated me and nourished a sense of wellbeing. Yoga satisfied me entirely, but I couldn’t clearly articulate why.

I was pracising Iyengar yoga twice daily, with a very approximate morning pranayama practice, and all I could have told you at the time was that it was both immensely challenging and rewarding, I felt very well from doing it, and my work and focus improved. Was I practising a mental or a physical discipline? In those days that was the main bone of contention amongst people who discussed yoga. Mr. Iyengar was constantly being asked if what he did was purely physical gymnastics, still a bit of a sore point for him today.

Is what we do Hatha yoga, posture work for the sake of physical wellbeing? Iyengar yoga regards the body as a vehicle for self-exploration, to perceive the mind, to develop a quality of reflectiveness, a tool to employ for greater self-awareness so that yoga practice becomes a mirror to the self.

Iyengar yoga to develop physical and mental health

Physical health is essential to a healthy mind and many mental distractions such as anxiety, inability to concentrate, and sleeplessness can be exacerbated, even caused, by physical imbalance and ill health. But a more flexible, more toned, more responsive body is a by-product of yoga. The body is seen as the temple of the soul and therefore worthy of respect, an instrument with which to express our mental and spiritual being. Through it, we can see ourselves and the consequences of our actions more clearly, but it is not an end in itself. The purpose of yoga is not to beautify the body, though it may indeed become more radiant.

The purpose of all yoga is, according to the 2000-year-old text of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, to restrain the fluctuations of the mind and bring greater self-knowledge. The body is a means, the mind being more elusive, the body more tangible. Mr. Iyengar has often said that the postures are not a stand-alone part of yoga and that the eight limbs of Ashtanga Yoga are not meant to be seen in a hierarchical fashion, with yamas (moral precepts) at the bottom and samadhi (enlightenment) at the top. The aspects all interact and are intertwined, each as significant as the other so that he describes the postures, practiced with awareness and focus, as ‘meditation in action’. However, as Mr. Iyengar notes in ‘Light On Yoga’, the deeper aspects of yoga cannot be experienced without a quiet mind and that ‘for the ordinary man or woman in any community of the world, the way to achieve a quiet mind is to work with determination on two of the eight stages of Yoga mentioned by Patanjali, namely, asana and pranayama’.

The scope and variety of his teaching are vast because the postures are there to inform us and there are infinite ways to use them.

Mr. Iyengar has taught classes using the sutras and even the chakras as reference points. Iyengar yoga aims at developing clear and continuous attention, bringing consciousness to each and every part of the body in order to explore the effect of the mind on the body and the body on the mind. If we focus on the little toe of the back foot in a standing posture, we will discover how it’s position affects the rest of the leg and body, at the same time learning the art of fixing our mind to one point, gaining greater capacity for self -observation. The postures are vehicles for exploration, they are alive and have as many different facets as we do. Yoga, and Iyengar yoga, continue to change as our perception of it changes. Mr. Iyengar once said that the truth changes, bringing much consternation to our Western minds which crave rational certainty; we only see what our experience permits us to see, so yoga develops our faculties of perception.

What defines Iyengar yoga?

So what defines Iyengar yoga? At a talk at Mr. Iyengar’s 80th birthday celebrations in Pune in 1999, his son Prashant suggested three defining characteristics: technicalities, sequencing, and timing.

Technicalities are the precise and often subtle technical points given to explore the asana fully. Renowned in Iyengar yoga, sequencing is the way he has put together postures to achieve a particular physical, physiological, or mental effect. Sequencing can apply to postures, or even to points in postures, and can totally transform a practice. Timings are the ways that the postures can be held for different lengths of time to enable a more profound exploration of the physical and mental challenges in the pose. These three features together externally define the development of Iyengar Yoga, though representing only some of the aspects of yoga that Mr. Iyengar has highlighted and examined over his 65 years of constant practice. And that is just the beginning. Through yoga practice, our understanding moves from the visible and knowable to the more subtle. It is a continuous and lifelong process.

Violinist Yehudi Menuhin, who became a devoted pupil of Mr. Iyengar, made a significant contribution in bringing his yoga to the West in the early 1950s. The story goes that Menuhin was suffering from insomnia and cysts on his wrists, which were severely restricting his playing. He was introduced to Mr. Iyengar who put him in a specific yoga posture which relaxed him to such an extent that he fell into a proper sleep for the first time in months. Converted to the method through this first positive experience, he was taught postures for the cysts, which also disappeared. Menuhin, excited by this teaching, arranged for Mr. Iyengar to visit the UK, and became a life-long pupil.

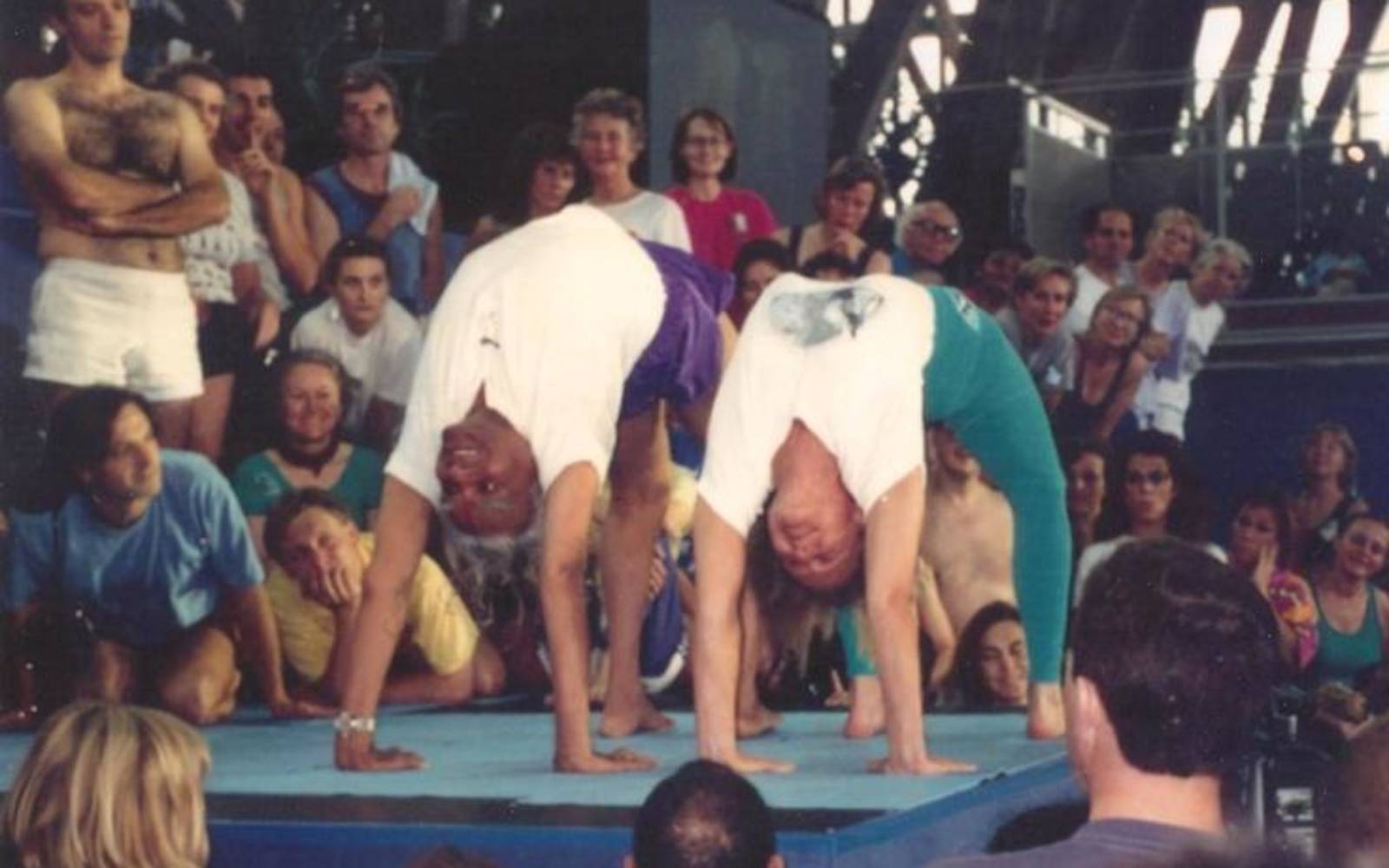

In his articulate foreword to ‘Light on Yoga’, Menuhin reflects that ‘The practice of Yoga induces a primary sense of measure and proportion. Reduced to our own body, our first instrument, we learn to play it, drawing from it maximum resonance and harmony… By its very nature, it is inextricably associated with universal laws: for respect for life, truth, and patience are all indispensable factors in the drawing of a quiet breath, in calmness of mind and firmness of will.’ Through their association, Mr. Iyengar began to teach during the Menuhin Music Festival in Gstaad, Switzerland, and subsequently taught in London during his increasingly frequent European visits. The USA followed, and in 1984 Australia had its first taste of Iyengar yoga as taught by Mr. Iyengar himself. His method has continued to expand with teachers and schools blossoming around the world.

New Zealand-born Martyn Jackson, amongst the early group of westerners to study with Mr. Iyengar in Pune, started the first Iyengar yoga school in Australia in Bondi Junction in the mid1970s. His great enthusiasm and personal warmth inspired many to practice yoga, including most of the contemporary senior Iyengar yoga teachers in Australia. His challenging teacher training course, held from 5am to 8am at least five days a week, almost certainly inspired the tradition of early morning Iyengar classes which exists nowhere else in the world quite like it does in Australia.

In Australia, Martyn pioneered the idea of yoga being taught in a centre where there was one principal teacher, or maybe two, being joined over time by other less experienced teachers all trained at that school. Now a feature of the Iyengar tradition in Australia, each centre has its own character or flavour but adheres to the disciplined tradition of Iyengar Yoga.

Teacher training standards in Iyengar yoga

A number of senior Australian Iyengar teachers conduct 300–500-hour teacher training courses, and teacher standards are maintained by very a rigorous certification system. Senior teachers guide less experienced teachers in their ongoing professional development, and all teachers visit Pune regularly to further their study with the Iyengar family. Knowledge of the Iyengar technique is essential for a good teacher, but so too is the capacity to communicate to one’s pupils the art of yoga as learned from, and based in, the teacher’s own practice.

Of all the aspects of Mr. Iyengar’s approach, the one that stands out to me is his devotion to a practice full of heart and a practice which is pure mindfulness, reflection, and introspection. These are the qualities to which practitioners aspire, the inner grace and light, mental relaxation within the physical form of the pose. Perhaps this is what Patanjali refers to as ‘effortless effort’.

Ultimately yoga comes back to us, to our real intent. Are we satisfied with the outer trappings of this subject or can we reach for knowledge which is gained from personal experience, not from intellectual playing? When Mr. Iyengar launched ‘Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali’, he said that, like with his previous books ‘Light on Yoga’ and ‘Light on Pranayama’, it had taken him perhaps 25 years or so to write because he wanted his books to be born out of genuine, subjective understanding, not from literary research. This takes patience and perseverance, two skills required for yoga in general. The beauty is that whilst yoga demands certain qualities, it also gives us the tools to acquire them. Practice is all it takes.