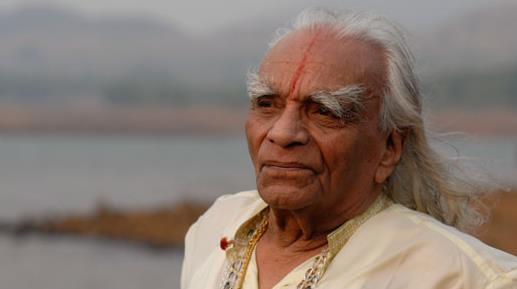

The term “Iyengar Yoga” was coined to describe the method of teaching Yoga developed by BKS Iyengar. Iyengar, however, states:

I have no right to brand my method of practice and teaching as “Iyengar Yoga”. It is my pupils that call it Iyengar Yoga to distinguish it from the teachings of others. Though I am rational, I am a man of sentiment and tradition bound. I trust the statements of others, follow their lines of explanation and experiment with them to gain experience. If my experience tallies with their expressions, I accept their statements. Otherwise I discard them, live by my own experiments and experiences, and make my pupils feel the same as I felt in my experiments. If many agree, then I take it as a proven fact and impart it to others …

… The only thing I am doing is to bring out the in-depth, hidden qualities of yoga to the awareness of you all. This has made you call my way of practice and teaching “Iyengar Yoga”. This label has caught on and become widely known, but what I do is nevertheless purely authentic traditional Yoga. It is wrong to differentiate traditional from Iyengar Yoga.

If we accept the statements above, then Iyengar Yoga is a method of examining, and gaining experience in, the field of Yoga. In the following article, I have attempted to define the attributes of Iyengar’s method.

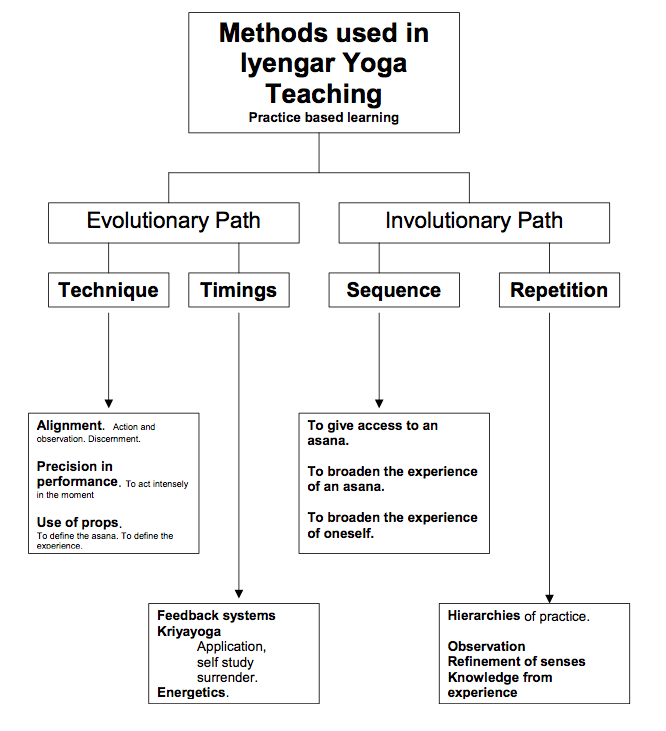

To do this I have defined four categories:

- Technique

- Timings

- Sequence

- Repetition

The first pair, Technique and Timings, forms the developmental, Evolutionary pathway in practice – the pathway to investigate, refine, and know the practice. The second pair, Sequence and Repetition, forms the Involutory pathway within practice – the pathway of self-study (Svadhyaya).

Technique

Classes in Iyengar Yoga are noticeable for their attention to detail. These precise, systematic instructions shape our performance of the asanas. Defined as technique, I divide this detail into three component parts:

- Alignment

- Precision in performance

- Use of props

These three together form the composite of technique.

Alignment

Alignment is fundamental to the practice of Iyengar Yoga. Each asana is defined specifically and the student measures their performance and ability in relation to the ideal of the asana. Broadly speaking, it is a developmental aspect by which the student progresses. Contained within the act of aligning the body is the principle of coordinating mind and body in the act of asana. Measuring tension and stretch requires action and observation.

However, in addition to the development of the asana, discernment is required. In refining the alignment of an asana, we must also evaluate and discriminate between the intensity of the sensation (that which inflames the senses) and the faculty of mind, which can move beyond emotion and effort, in order to weigh the performance in the tissue in comparison to the teacher’s instruction.

Precision in performance

Precision in performance is the art of linking one’s attention to the action not merely for the sake of alignment. Precision in performance requires continuity of attention and presence in the asana. It requires that the student enter the moment in order to act and observe now. In his commentary on the Yoga sutras, Iyengar states:

The conjunction of effort, concentration, and balance in asana forces us to live intensely in the present moment, a rare experience in modern life. This actuality, or being in the present, has both a strengthening and cleansing effect: physically in the rejection of disease, mentally by ridding our minds of stagnated thoughts or prejudices; and, on a very high level where perception and action become one, by teaching us instantaneous correct action; that is to say, action which does not produce reaction. On that level we may also expunge the residual effects of past actions.

Iyengar describes this entering the moment of experience in the following way:

Moment is subjective and movement is objective. Patanjali explains that the moment is the present and the present is the eternal now: it is timeless, and real. When it slips from attention, it becomes movement, and movement is time. As moment rolls into movement, the past and the future appear and the moment disappears. Going with the movements of moments is the future; retraction of this is the past. The moment alone is the present. Past and future create changes; the present is changeless. The fluctuations of consciousness into the past and future create time. If the mind, intelligence and consciousness are kept steady, and aware of moments without being caught in movements, the state of no-mind and no-time is experienced. This state is amanaskatva. The seer sees directly, independent of the workings of the mind. The yogi becomes the mind’s master, not its slave. He lives in a mind-free, time-free state. This is known as vivekaja jnanam: vivid, true knowledge.

Again, in a second passage on time, Iyengar says:

Yogic discipline eradicates ignorance, avidya. When illusion is banished, time becomes timeless. Though time is a continuum, it has three movements: past, present and future. Past and future are woven into the present and the present is timeless and eternal. Like the potter’s wheel, the present – the moment – rolls into movement as day and night, creating the impression that time is moving. The mind, observing the movement of time, differentiates it as past, present and future. Because of this, the perception of objects varies at different times.

Though the permanent characters of time, the object and the subject remain in their own entities, the mind sees them differently according to the development of its intelligence, and creates disparity between observation and reflection. Hence, actions and fulfillments differ …

The yogi is alert to, and aware of, the present, and lives in the present, using past experience only as a platform for the present. This brings changelessness in the attitude of the mind towards the object seen.

It is clear from these two passages that a practice should bring the student into the moment. The act of entering the moment through technique has a profound effect in that we become free of our habitual mode of being, able to move beyond the normal constraints of identity, internal dialogue, and self-image. A practice which is reduced to alignment and does not enter the moment is merely a recreation of the past.

When our practice enters the moment we do more than dissolve time. We establish the environment by which to study our interaction with an object (our practice). We re-orientate our focus from being a study of asana to become a study of ourselves.

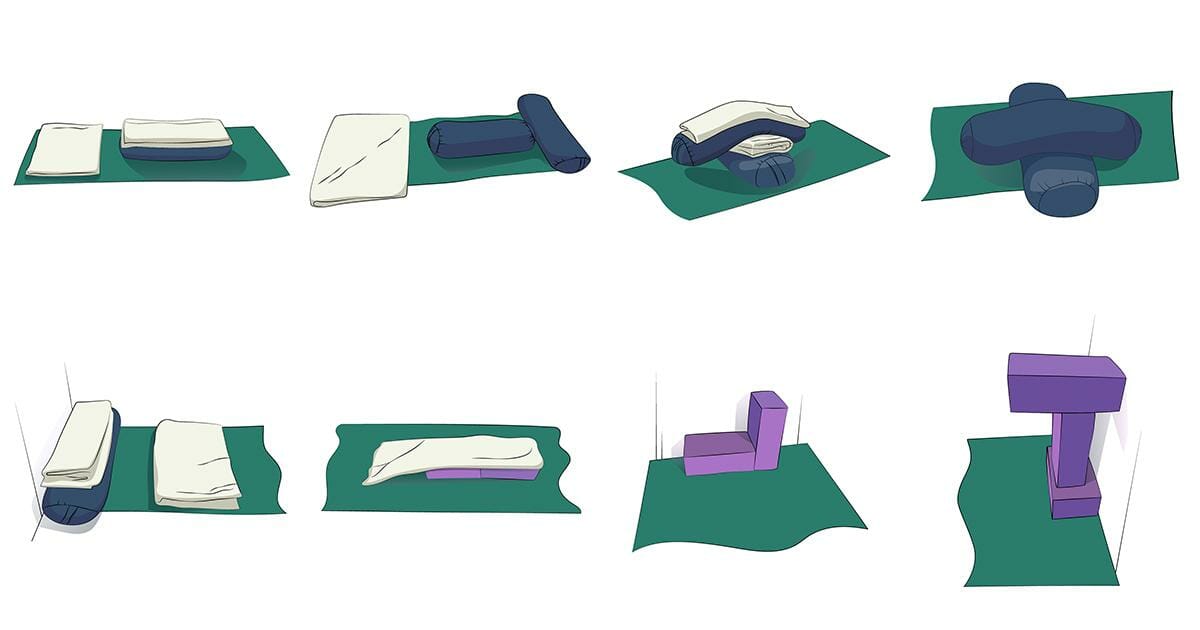

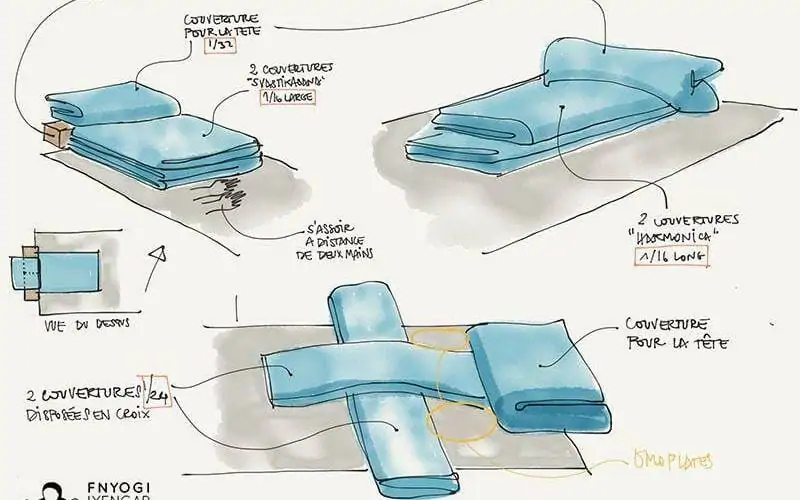

Use of props

The use of props is another notable example of technique. Props, or supports, are used extensively in Iyengar’s method.

In a talk about props, Geeta Iyengar says:

Years back it was difficult for people to accept the very idea that we could use props while doing asanas or pranayama. The idea was that everything should be done independently and if you used a support it was not the traditional way. It is hard to believe that years back even I could not express this when writing articles because people were against it. Yet we were using props when teaching classes or handling different patients and their problems. Then gradually, when people started feeling they were improving, the psychology changed. The minds of people started changing, and now we have reached such a stage that people ask for further demonstrations with props. We did it not only here but in Pune, Bombay, Rishikesh and different areas. Not only has the interest been ignited but also now doctors even think in a different way. They think that if we can use these props for patients in the hospital it may bring a great change.

Even for Guruji, it was not easy to create props but definitely there was something in his mind. I would say he was always in yoga in that sense. Even now he thinks in a different way to others. There was not an authoritative book regarding props but certainly, the clues were available. Guruji began to think about these props. His practice gave shape to the props.

In Hatha Yoga Pradipika in the very first chapter in the initial stanzas, we come across the list of practitioners, the yogis, and among them, one called Chaurangi is specifically mentioned. He was disabled. When Guruji read this he started thinking about this person who was disabled. He could not walk or stand but was a practitioner and was considered to be a great yogi and was even cited in the list of great names. In the same chapter, you find the stanza saying, ‘The young, the old the extremely aged, even the sick and the infirm obtain perfection by constant practice’ (Hatha Yoga Pradipika 1:64). That definitely gives the clue that some other ways existed in those days. People who had diseases or those who were disabled could take up the practice of yoga.

Similarly, Guruji could feel when practising backbends like Viparita Dandasana, Kapotasana, or even Vrschikasana, which are advanced poses. He could feel from within that such asanas were a great help to him to open his chest or open his lungs inside. They were bringing freedom in the breathing. This started him thinking about people with asthma, colds, or a cough who were weak and not strong enough to do advanced postures. Everyone cannot perform these difficult postures and yet they are very effective. How to introduce those difficult postures? How to bring that specifically required effect he experienced in those asanas. What could help a particular disease? Someone may have a lung problem; someone may have an abdominal problem, an intestinal problem.

The question remained how to make everyone able to do these difficult postures. People were afraid. People did not believe Guruji: ‘These are so difficult and why are you making us do these difficult asanas.’ What he started to do was to help with his own hands and legs – using his own body as a support. If someone’s chest had to be opened he would grip their back ribs with his hands and fingers, supporting with the palms, lifting the chest so it could relieve them and take off their fear. It is true some people would be afraid when someone else was touching their body. Afraid that their bones would break or a joint would slip off or anything could happen. But Guruji was confident about it because of his own practice. He knew exactly where and what had to happen; in which way it should be done. That is why he started using his own hands, arms and legs for support. People could do asanas comfortably and get the effect that was expected.

That is how props came into the picture.

I am telling you this because sometimes people may question why we use supports. The supports are not meant just to rest and relax or to do in a lazy way. They are meant to obtain the feeling of the correct asana from inside so we can improve ourselves. Whenever we have that nervousness, the fear complex, our movements are restricted. We may not know that the movements are restricted unless somebody guides us. In this way, the props are of a great use because they open new avenues for every practitioner.

Patanjali did not forget these kinds of props but he refers to them in a different way in his Yoga Sutras. For example, in the first chapter Patanjali speaks of the consciousness or the chitta which comprises the mind, the intellect, and the very ‘I’ expression. The capital ‘I’ expression – this consciousness cannot be quietened straight away. People often ask us – they come and say, ‘I want to do yoga, my mind fluctuates very much. Can you stop the fluctuating of the mind?’ They think the teacher is supposed to stop the fluctuations of the mind! But Patanjali says the fluctuations of the mind will not stop straight away. You need to polish your consciousness, you need to embrace your consciousness and you have to see that the consciousness, which we have within, becomes more graceful in its expression.

So what are the ways props are used?

The primary reasons to use props can be categorised in two broad definitions:

- Props define the asana

- Props define the experience

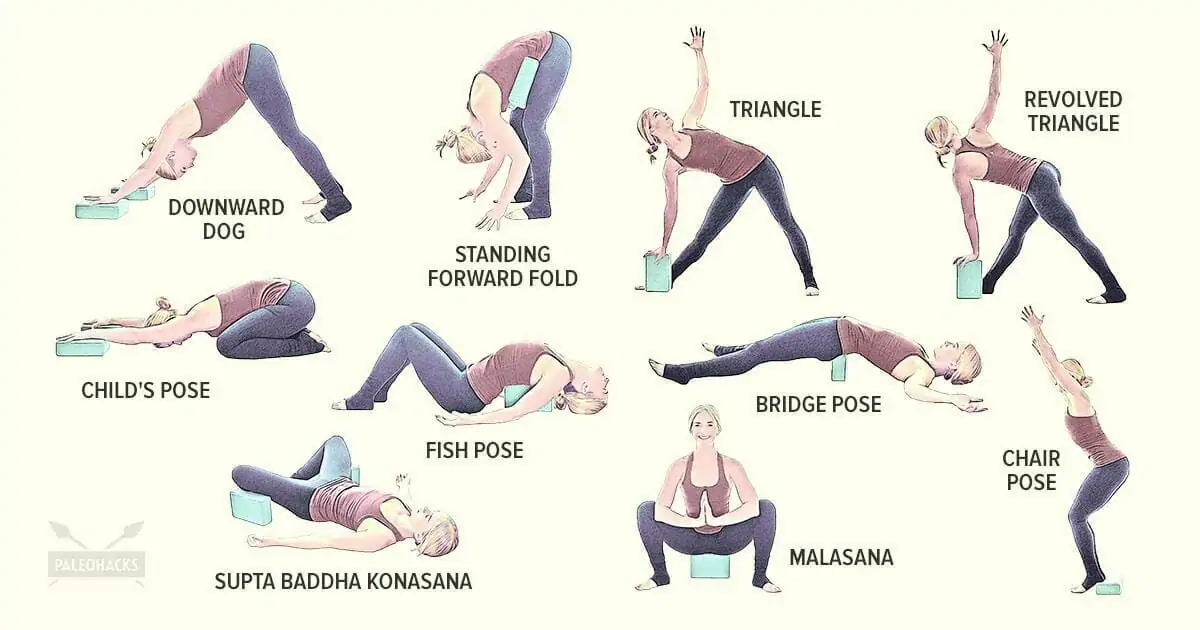

Props define the asana

Props:

- increase the duration of staying in an asana;

- increase confidence in the practitioner;

- increase subjective knowledge of accurate alignment;

- increase range of motion;

- help to achieve an asana that is not possible without the prop.

A prop is used to define the asana:

- it may be positioned to limit the movement in one part of the body to emphasise the stretch in another (for example, a block wedged between the wall and the front knee in Virabhadrasana 1 to emphasise the back leg);

- it may be used to energise an area (for example, a belt on the elbows in Sarvangasana to create lift in the spine);

- it may be used to connect one part of the body to another (for example, heel to wall in Trikonasana to extend the spine).

Props define the experience

In an article printed in Yoga Rahasya 2004, Prashant Iyengar describes how the use of props are used to annihilate fear, to bring physical and mental stability, to bring humility (involute):

Props bring the asana to the level of the student

A prop brings in the feeling of lightness: In the 43rd sutra of the Vibhuti Pada, Sage Patanjali says that an accomplished yogi attains lightness in the body and he is even able to levitate. This sutra clearly gives us a clue as to what we should aim for in our practice of asanas. We all ‘enjoy’ the asana when the body feels light. That is exactly what the props do. For example, when Ardha Chandrasana is performed with the support of the trestler, and the lifted hand is used to revolve the chest, the chest opens. We are able to take in the cosmic energy as the chest opens. Thus, we never feel the fatigue but instead feel light and energised by the asana.

Props develop sensitivity in the practitioner

As beginners, we start our asana practice through the gross body. We tend to use only the muscular body but as we continue, we need to attain the sensitivity to feel the asana through the skin and the senses. The prop aids in developing sensitivity. For example, when we are performing standing asanas against a trestler, we can learn what the source of action is. Once we make any particular action we can study the range of its effects. Sparsa, contact, is an important component of practice. Sensitivity develops when we have some external contact and that is how the props guide us. It is for us to use this sensitivity to trigger our intelligence. The props give us a spark of light but we fail to catch it. For example, when we are doing Ardha Chandrasana, the leg on which we stand tends to become shorter. The moment we perform the same asana with the trestler, it automatically becomes longer. It is for us to ‘catch’ what the prop does to us. In Sarvangasana, the frontal thighs tend to collapse if we stay longer in the asana and they feel very fatigued. But, if we loosely tie a belt around the bottom calves and move the legs outwards to touch the belt, we will observe that the frontal thigh muscles naturally recede towards the bone and there is no fatigue in the thigh muscles. So we have to study what the props do to make us perform the asana with greater ease. Their use sparks our intelligence. We have to ‘catch’ these sparks and clues that we get with the props. We should then try to incorporate them while performing the asanas independently.

Props help to adjust the pranas in our system

The prana vayus are the life force in our system. We are comfortable in any asana as long as these vayus are balanced. For example, when the udana sthana is tensed or udana vayu overused the throat and along with it the brain feels choked. Many beginners often tend to unknowingly block or grip the udana sthana while doing the asanas especially the twisting asanas and also in sitting pranayama. Such practice can be harmful to the practitioner. The use of props automatically adjusts the prana vayus in our system. For example, vyana naturally drops while doing Savasana on the floor. The vyana pervades the entire system and can be observed on the lateral sides of the chest. But, the vyana naturally lifts when a bolster or pillow is used to vertically support the spine in Savasana. In Urdhva Mukha Svanasana, the samana (located around the abdomen) and the vyana tend to drop. However, when Urdhva Mukha Svanasana is performed with the palms on a chair or a Viparita Dandasana bench then the samana and vyana both get lifted. We feel lighter and energised.

We should not always use a prop as a crutch or a sofa to flop ourselves on! We should be very clear in our minds as to why we are using a prop for a particular asana on a specific day. We should use the prop to trigger our intelligence and generate life in our practices just as Bheesma Pitamah used the bed of arrows to trigger his intelligence and keep himself alive!

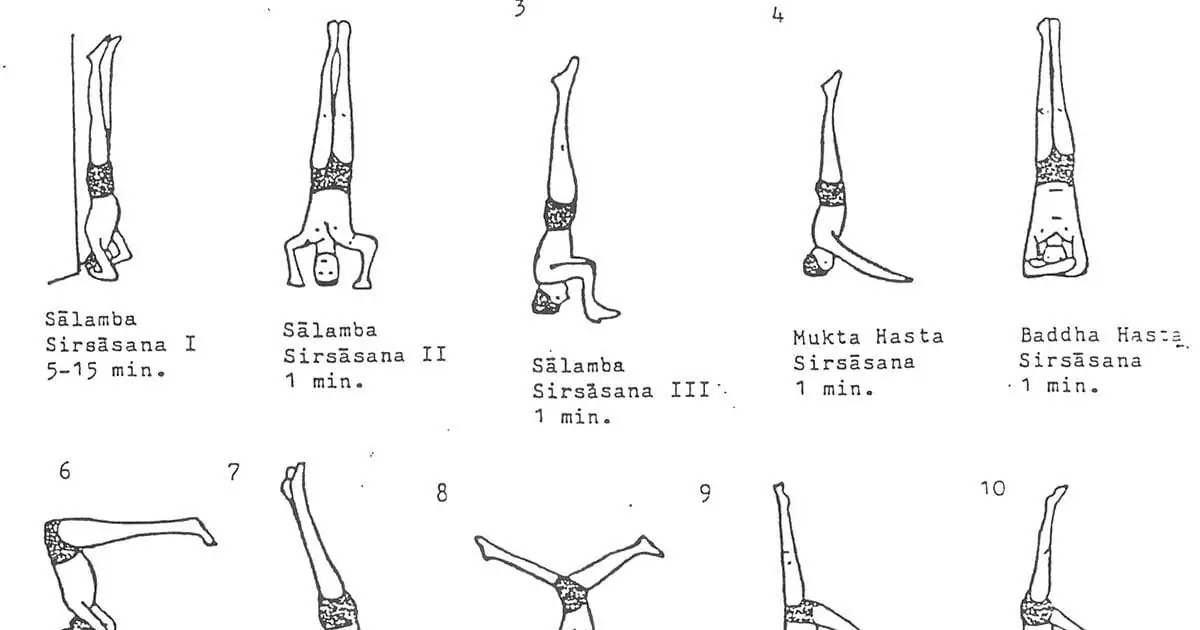

Timings

A second fundamental aspect of Iyengar Yoga is the use of timings. Iyengar Yoga places an emphasis on this aspect of practice in a way that other methods of Yoga do not. I would like to examine three aspects of timings:

- Physical conditions (feedback systems)

- Kriya Yoga: tapas, svadhyaya, isvara pranidhana

- Energetics of asana

Physical conditions (feedback systems)

On the physical layer, when we stretch a muscle and hold it, the internal fibres will adjust more efficiently if the stretch is maintained. We could say the stretch is more effective if it is prolonged. This however is not completely correct because if the stretch is too strong the nerve receptors within the muscle fibre (nociceptors) will trigger and the muscle will contract. The muscle increases its contractive force.

For this reason, the practitioner must be sensitive to how much stretch is applied to the muscle; too much stretch creates greater resistance. In order to stay in the asana the practitioner must observe and listen to the stretch. A feedback loop is established in which the mind provides the impetus, the sensation provides the feedback and the mind is made to observe and adjust. From action to observation. The practitioner must learn to read and modify in order to extend the timing.

Iyengar outlines his working method in the following passage:

While performing the asana you and I have to carefully observe that if the muscles are extended strongly and heavily with force, then the senses of perception can not receive the action done by the fibres, the cells and the spindles. The afferent nerves carry the message of pain rather than the actual functional imprint. They do not receive the actual functioning of the inner system which can only imprint on the senses of perception, the skin. They are felt later by the eyes and the ears as a pressure or a tension because of the overwork or wrong work. While performing asana one has to be careful that the spindles of the motor nerves of our system (the fibres of the muscles) should act without disturbing the fibres of the sensory nerves which are conceived by the senses of perception (the inner layer of the skin). If the muscle fibres are not overstretched, or jammed against the senses of perception, only then can the perceptory nerves receive the exact action done by the flesh. The efferent and afferent nerves work cooperatively to keep the balance between action and perception, in order to correct the position of asana and bring a healthy sensation. While we are performing asana, we have to adjust in such a way that the fibres of the flesh do not protrude against the skin more than is essential, otherwise the nerves and their elemental chemistry – earth, water and air – get disturbed.

Kriya Yoga

A more complex, philosophical rendering of timings includes the examination of Kriya Yoga (application, self-study, and surrender) through the use of timings. The following excerpt is taken from the introduction to Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali and presents the eight limbs of Yoga into their groups as represented by Kriya Yoga:

Kriya means action, and kriyayoga emphasizes the dynamic effort to be made by the sadhaka. It is composed of eight yogic disciplines, yama and niyama, asana and pranayama, pratyahara and dharana, dhyana and samadhi. These are compressed into three tiers.The tier formed by the first two pairs, yama and niyama, asana and pranayama, comes under tapas (religious spirit in practice). The second tier, pratyahara and dharana, is self-study (svadhyaya). The third, dhyana and samadhi, is Isvara pranidhana, the surrender of the individual self to the Universal Spirit, or God (Isvara).

In this way, Patanjali covers the three great paths of Indian philosophy in the Yoga Sutras. Karmamarga, the path of action is contained in tapas; jnanamarga, the path of knowledge, in svadhyaya; and bhaktimarga, the path of surrender to God, in Isvara pranidhana.

Tapas

Tapas is the quality of application, focus and effort. It is the heat we apply to go forward; to experience. Tapas is cleansing and purifying. It requires that we overcome obstacles within ourselves – the nine obstacles to practice are disease, inertia, laziness, doubt, heedlessness, indiscipline of the senses, erroneous views, lack of perseverance, backsliding. Classes are grounded in this level of tapas. Students are taught to inquire and define through asana and pranayama practice. The teacher informs the student on how to perform the asanas, refine their efforts, identify and overcome obstacles within themself. Tapas brings us into the moment to experience directly, unencumbered by thought. The use of timings in practice is used to remove the whimsical nature of mind that vacillates. Timings in asana make practice methodical and evaluative. The practice progresses and the mind becomes disciplined.

Through systematic practice, we become present in our acts and reshape the way our mind absorbs experience. Instead of interpreting things which happen to us through the filter of our mind (views formed from past experience), we move to experience them without the veil of thought. An example of this is where we have an experience in the past of someone abusing our trust – this often makes us wary of future interaction with others, but in the extreme, we become unable to trust anyone; our actions are limited by our beliefs.

In tapas, we experience directly. In doing so we burn off past impressions which limit our range of experience, and our ideas of what we are capable of change. Through action (tapas) we can refine our consciousness – change and grow.

Tapas is the first tier; it can not be transcended. When we apply tapas through timings we become methodical and systematic.

Svadhyaya

The second tier or layer – self-study – is seeing or examining ourselves in the performance of asana. Through practice, we must come to see ourselves and what we bring to our practice; habits, prejudice, beliefs all affect our progress along the yogic path but also affect us from day to day. Moods and emotions affect us in our practice and even our ability to get on the mat so that we need to cultivate dispassion and equanimity in our practice or become paralysed by our thoughts and actions.

Self-study is the quality which allows us to put aside judgement in our moment to moment performance of asana and pranayama to observe our interaction with the pose. In this way, it is a much more flexible quality than tapas – more watchful and forgiving than evaluative or judgemental. Often students merely repeat the instructions of their teacher when they practise. This mental set of words is taken as practice but is only the shell of practice. It is only when you are in the experience of asana, rather than the instruction, and you experience the doing and your interaction with the doing that time disappears. Self-study is the key to make practice meaningful. Timings provide a stable environment in which to cultivate observation of oneself. As we remain in an asana we observe the fluctuating consciousness, moods, emotions, and habits of thought.

Isvara Pranidhana

The term isvara pranidhana is directly translated as surrender to God. There is much discussion about whether Yoga is therefore theistic with many commentators arguing for and against. However, this assumes a creator God, external and omnipotent.

In her commentary on the Yoga Sutras, Barbara Stoller Miller makes the following comments on isvara pranidhana:

While dedication to the Lord (Isvara) is referred to in the Yoga Sutras (1:24) isvara is not a creator God. Patanjali does not furnish details, but the context suggests that he conceived the Lord as an eternal, archetypal Yogi, an object of concentration for the practitioner who seeks to achieve spiritual calm. Nowhere in the Yoga Sutra, is Isvara defined as an omnipotent god like Krishna in the Gita, who manifests himself as the lord of life and death.

Stoller Miller identifies isvara as the quality of surrender which the practitioner generates in order to diminish “I”ness which is essential.

A second commentator, Ian Whicher, in his book The integrity of the Yoga Darshana elaborates:

The term Ishvara was used by Patanjali largely to account for certain Yogic experiences (e.g. YS II:44 acknowledges the possibility of making contact with ones ‘chosen deity’ – ista-devata – as a result of personal, scriptural study – svadhyaya.

He further states:

Whilst classical Samkhya is said to be nir-isvara or non theirtic, classical yoga appears to incorporate a sa-isvara or theistic stance. However, it is simply not appropriate to label the Samkhya-Karika as being non theistic. Isvara Krsna, rather like the buddha, chooses not to mention or make any statement about God at all. According to the Samkhya-Karika if there is a God (there being no positive denial of God’s existence in the Samkhya-Karika) then such a being has little or nothing to do with the actual path.

Practice commences with the desire to progress and refine both in a physical and spiritual sense but over time this quality changes to commitment to a process of change – an unfolding of that process. We eventually learn to surrender to change and allow it to take us where it will. Often we desire change but are equally terrified by it when it does not fit our vision, so our desire is conditional. Surrender is the quality of giving in to the unfolding of practice – it is a maturing of practice. It is a humbling of the yogi before the vastness of the subject and the immensity of the task they undertake within themselves to live this life of Yoga.

Many of the longer timings require a giving up, or giving in, in order to go on. The struggle to overpower the muscles transforms as we let go of identity.

Energetics of asana

When we work with timings we must adapt ourselves in relation to the challenge set by each individual asana being performed. An asana may require determined effort, strong application, the ability to maintain a fixed point of focus or, alternatively, to remain quiet, to stabilise, to wait and observe, to diffuse attention. Each set of asanas and each individual asana has an individual set of factors that must be engaged with. We study the energetics across asana groups and individual asanas.

For example, if performing Virabhadrasana III the appropriate balance of effort, extension and poise must be applied by the practitioner, otherwise the pose collapses or is strangled in the attempt.

In this way, as we explore the practice through timings or holdings, we also explore aspects of ourselves that may not normally be accessed. It is possible to broaden our range of responses to situations and experience. Through timings the following skills (to name a few) become possible:

- sustained application;

- stability in concentration;

- balance of the body;

- balance of mind / breath / body;

- continuity of attention;

- tenacity;

- quiet observation.

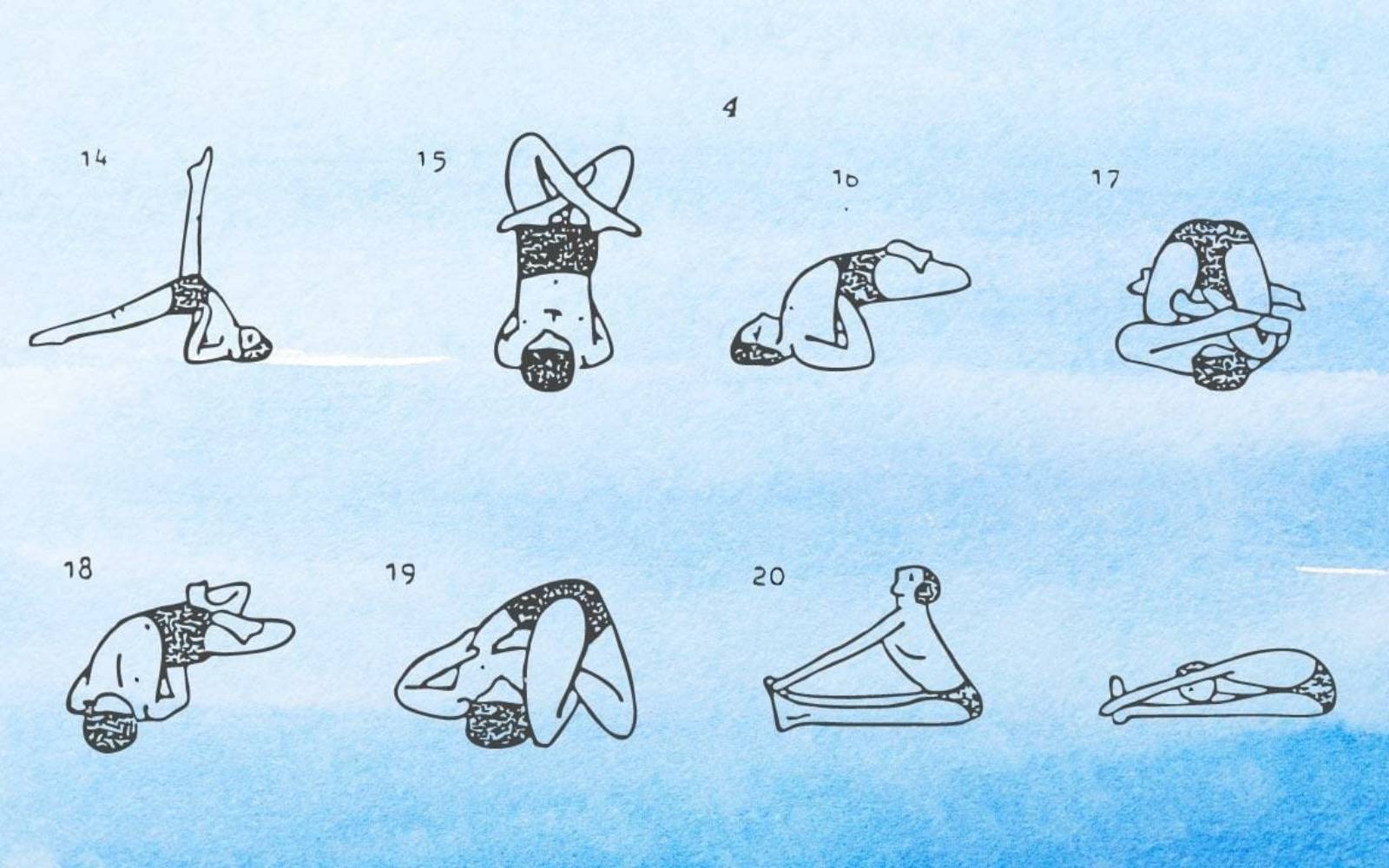

Sequence

When we sequence asanas we alter their effects on the body and on the mind. Some asanas stimulate and others relax and pacify. Groups of asanas sequenced well can produce a state of mind not encountered before.

In this way, by sequencing, we can examine the physical, mental and emotional aspects of our existence.

Asanas can be sequenced in the following ways.

To give access to an asana

- Sequenced one after another to prepare the body for a particular movement. In effect, we make an asana easier if we place it in the sequence in such a way as to prepare the body for the movement needed.

To broaden the experience of an asana

- Knowledge by association is derived when we practise in the following ways:

- By altering our association and understanding we can affect the way the mind views the asana and therefore its performance.

- We add new perspective to the way we understand an asana whenever we examine the influence of one asana upon another. For example, if we alternate between Baddha Konasana and Janu Sirsasana we are able to see how hip and groin opening affect the forward bend of Janu Sirsasana (an asana normally associated with hamstring extension).

- Altering the experience in the body – by changing the position of an asana in the sequence we can alter the way an asana is experience. For example, if we place Ardha Halasana (with support for 10 minutes) before Sarvangasana, then Sarvangasana will feel much quieter and more focused.

The ability to remain in the asana is enhanced and our understanding of how to perform the asana is progressed by affecting how the asana feels when we do it.

Both methods are used to change perspectives and assumptions within practice. This methodology recognises the tremendous influence mind has on our experience of the world and in practice.

To broaden the experience of oneself

The way we sequence asanas has an accumulative effect. If we practise a group of restorative asanas (a supported posture held for a specific time) it is possible to slow the internal chatter of the mind and alter the psychological experience of oneself. By utilising sequence to enhance our engagement in and to explore our practice, we study the effect of practice upon the mind and body.

Repetition

The practice of Iyengar Yoga emphasises a high level of repetition in practice. Far from being a method of perfecting asanas, it is a method of clarifying one’s perception. We do more than just study the asana; we study ourselves in relation to the asana.

In a talk given in 1998, Prashant Iyengar made the following statements:

One of the most important aspects of Iyengar Yoga is hierarchy in practice. A beginner may be taught Trikonasana in his very first class while Guruji also practices Trikonasana after 70 years. Both these asanas are Trikonasana but the quality of the asana is totally different. For a beginner, the asana is totally on the skeletal plane whilst Guruji’s Trikonasana would be in a state of mediation in Trikonasana. A beginner’s Trikonasana would be controlled and guided by his/her teacher whilst Guruji’s Trikonasana would be guided by his citti.

Thus, as students of Iyengar Yoga, we have to practice asana and progress in the hierarchy of our practice. We should align our sharira. It is imperative to mention here that sharira which is loosely translated as body in English, in reality encompasses our breath, mind, senses, intellect and emotions. So although we start with physical alignment, we have to progress to include the complete meaning of the sharira.

We should evolve so as to time our practices not only by the clock but to perform them to attain sthirata and sukhata with the practice being progressively being governed by the will, mind, breath, intelligence and finally the citti.

From this talk, we can note the ascending levels of refinement whereby we develop a practice from its gross presentation in the physical plane through refinement to become a more subtle practice. This physical practice where the body is positioned with alignment and precision engages the senses (jnanendriyas) so that gradually the senses become absorbed in the activity. Patanjali describes this process as inverting the senses – to internalise the senses (pratyahara). When the jnanendriyas become absorbed in the activity of practice the mind becomes steady. The mind, which normally jumps from thought to thought and follows its own oscillations, becomes quiet. And so our practice, which is so much formed by the physical, should encompass the other sheaths (kosas) of our existence.

It is through repetition that we begin a process of involution. Iyengar refers to this as the means by which we refine and culture the consciousness. He says:

- The culture of consciousness entails cultivation, observation, and progressive refinement of consciousness.

When considering the statements above, the application of repetition as a method can be understood as a means of directing students’ experience towards:

- observation;

- refinement of senses (jnanendriyas);

- knowledge from experience; it confirms or refutes.

Observation

Observation is fundamental to a practice of Yoga. Observation (vairagya in its gross form) is the balancing force to sustained action (abhyasa). Observation in practice requires that we are capable of separating from the experience in order to observe dispassionately.

We must distinguish between the experience coloured by mental/emotional influences and what happens in the physical plane of the asana. Being present as an observer to the act rather than someone with a vested interest or participant enables us to differentiate experience. This allows us, for example, to see the nature of our thoughts as opposed to the thoughts themselves. Unless this is achieved, the clarity of the perception is clouded and confused as the asana is experienced across the sheaths (physical, physiological, mental/emotional, intellectual). With practice in observation, the mind becomes a watcher as well as participant to the experience.

When we practise in repetition we form the foundation by which to familiarise ourselves with the asana; for the asana to become known. Observation orientates and expands the map of how we understand the asana. This constancy in application is essential to progress so that an asana becomes more than just stretching. It becomes a Yogasana.

Refinement of the senses

As observation increases in the asana, it is possible to direct repetition towards the refinement of the senses. The senses of perception – named the jnanendriyas – are said to be the bridge between the outer and the inner world. Because we experience the world through our senses the jnanendriyas are the means by which we become entangled in the world of objects. This entanglement leads to desire and aversion. The jnanendriyas are also the means by which we refine our consciousness and can transcend this dynamic.

As a beginner, these intense asana sensations dominate and often overwhelm our senses. The untrained senses are consumed by what the asanas require and project. As a result, the outwardly directed senses stimulate the mind, which becomes agitated. However, as we apply repetition to practice and refine our sensory involvement with the asana we can engage the subtlety of the asana experience. The mind can be directed to focal points in the asana and not merely the recipient of the experience. The mind can be trained to become absorbed in the experience before it and it develops concentration (dharana); we clean the lenses of perception through which we receive the world.

Repetition proves conclusively the changing nature of our experience – the way sensation can change and be influenced by tiredness, interest, moods, thoughts, and breath.

Knowledge from experience

A practice in Yoga aims to examine our experience in order to clarify through direct perception (pramana). The mind is volatile and inclined to quickly grasp concepts, but it is inclined equally to wander off. In doing so it misidentifies and confuses experiences. Through repetition, we verify what is assumed and either confirm or refute our ideas.

As a discipline, however, repetition is capable of diffusing thought by confirming one in sensation. Mind (manas), always moving, is returned again and again to the asana object. Repetition develops patience and continuity so that the mind becomes stable within the asana. From this develops the desire to know, not merely the desire to do.

Repetition develops clarity of perception so that this practice, which is conducted in the physical body, provides the means by which we can examine our actions such that we connect and interconnect from the core of the being to the periphery.

Conclusion

Ultimately a practice of Yoga is a structure by which we examine ourselves. Desires, fears, assumptions, and beliefs underpin and colour perception. A practice which is systematic, applied, and methodical will cleanse the lenses through which we perceive and encounter the world.

The following excerpt is from Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali:

Actions

Actions are of four types. They are black, white, grey, or without these attributes. The last is beyond the gunas of rajas, tamas, and sattva, free from intention, motivation, and desire, pure and sourceless, and outside the law of cause and effect that govern all other actions. Motivated action leads eventually to pride, affliction, and unhappiness; the genuine yogi performs only actions which are motiveless: free of desire, pride, and effect.

The chain of cause and effect is like a ball endlessly rebounding from the walls and floor of a squash court. Memory, conscious or sublimated, links this chain, even across many lives. This is because every action of the first three types leaves behind a residual impression, encoded in our deepest memory, which thereafter continues to turn the kamic wheel, provoking reaction and further action. The consequences of actions may take effect instantaneously, or lie in abeyance for years, even through several lives. Tamasic action is considered to give rise to pain and sorrow, rajasic to mixed results, and satvic to more agreeable ones. Depending on their provenance, the fruits of action may either tie us to lust, anger, and greed or turn us towards the spiritual quest. These residual impressions are called samskaras: they build the cycles of our existence and decide our station, time, and place of our birth. The yogi’s actions being pure, leave no impressions and excite no reactions, and are therefore free from residual impressions.

Desires and Impressions

Desires, and knowledge derived from memory and residual impressions, exist eternally. They are as much part of our being as is the will to cling to life. In a perfect yogi’s life, desires and impressions have an end; when the mechanism of cause and effect is disconnected by pure, motiveless action, the yogi transcends the world of duality and desires and attachments wither and fall away.